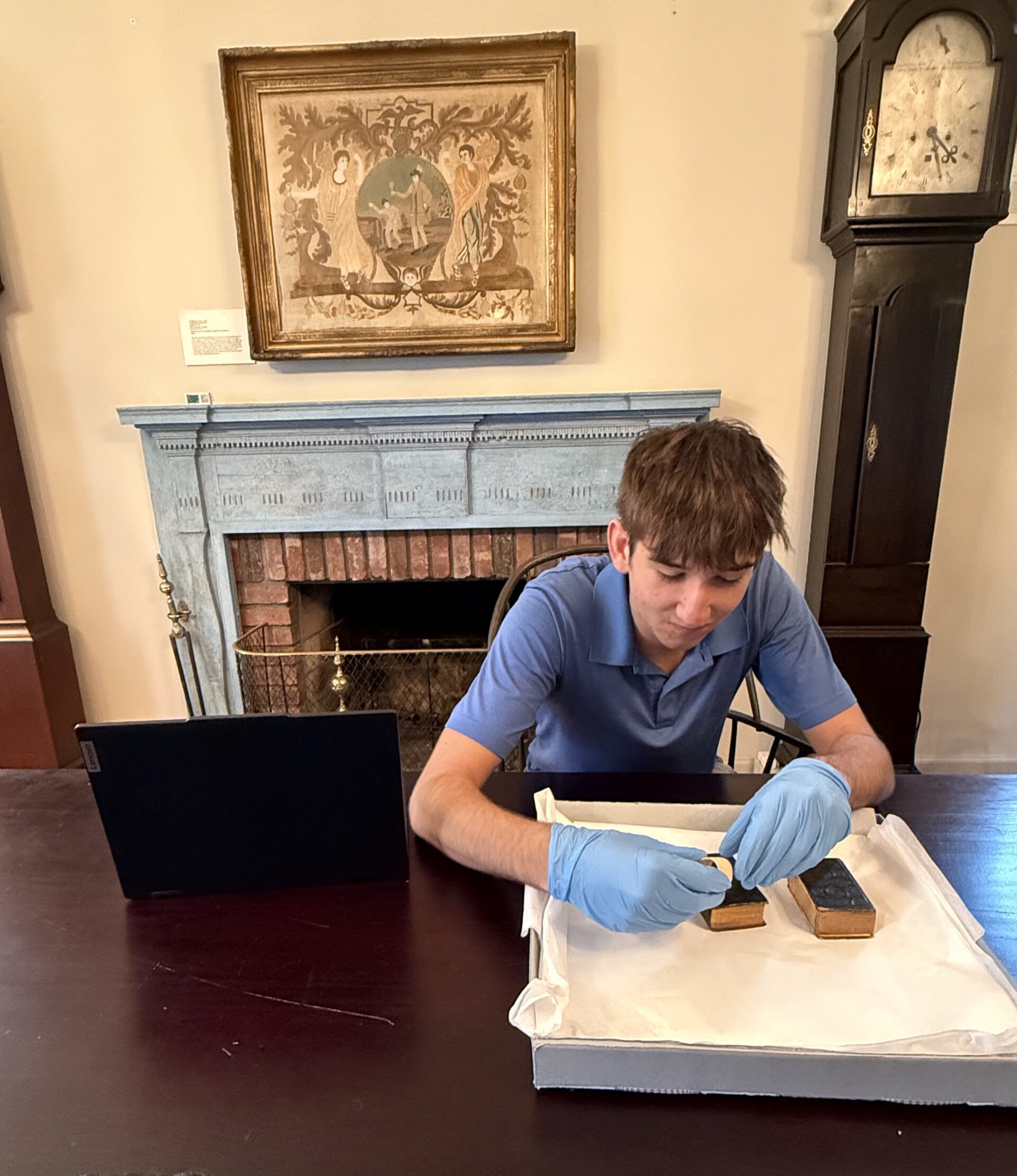

We are pleased to welcome to the blog, Tommy, a high school collections intern, who spent this summer researching objects in Preservation Long Island’s collection related to the life and service of Civil War veteran, Obadiah Jackson Downing.

This summer, I interned at Preservation Long Island as a high school student who is fascinated by Civil War history. On my first day, I mentioned this interest and was introduced to a remarkable pair of artifacts: a set of bone napkin rings that Civil War officer, Obadiah Jackson Downing (1835–1925), made during his captivity as a prisoner of war. Downing’s great-great grandson recently gifted them to Preservation Long Island along with other personal items that once belonged to the Civil War veteran. Not only was Downing a decorated war hero (and evidently a talented carver), he was also a Long Island native born in Hempstead.

Obadiah Jackson Downing enlisted in the 2nd New York Cavalry in 1862, a year after the start of the Civil War. He was initially commissioned as a second lieutenant, but rose through the ranks of the Union Army to become a colonel by the time of his honorable discharge in May of 1865. Downing fought in around 130 battles, including the key engagements of Second Manassas (1862), Fredericksburg (1862), Brandy Station (1863), and Gettysburg (1863). In particular, his conduct under fire during battles around Brandy Station in northern Virginia received praise from his superiors. In October of 1863, Downing saved his entire command of 50 men who were cut off from the rest of the Union Army by executing a daring charge straight into Rebel cavalry units. He was later taken prisoner by Confederate forces near Richmond, Virginia after the Battle of Yellow Tavern on May 12, 1864. His capture was notable enough to be reported by the Richmond Examiner, likely due to his officer status.

Downing’s time as a prisoner of war is fascinating. He was initially held at Libby Prison in Richmond before transferring to Camp Oglethorpe near Macon, Georgia and then Castle Pickney in Charleston, South Carolina. Enduring contaminated drinking water, starvation, exposure, and unspeakable conditions, Downing attempted escape three times but was never successful. He remarkably survived more than nine months of imprisonment and was later released in a prisoner exchange in February 1865. Upon his return to the Union Army, Downing became aide-de-camp to Brigadier General George Custer (1839–1876), and helped lead the victory processions of the Union army in Washington, D.C. While on one of his final assignments to deliver captured Rebel flags to Washington, Downing attended the performance of Our American Cousins on the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. He is believed to have assisted in moving the mortally wounded president across the street to his deathbed. After resigning his commission in the army in 1865, Downing returned to Long Island and was active in the New York Legislature. He later moved to Illinois, where he operated several successful businesses.

During his time as a prisoner of war, Downing made what are believed to be napkin rings from found pieces of bone. He probably carved them as a gift for his mother, Mary Jackson Downing (1805–1880), and intended to give them to her upon his return home to Long Island. Measuring about one inch in diameter, the napkin rings feature multiple inscriptions, including “MOTHER” and “MY DEAR MOTHER,” demonstrating his love for family. Also carved on the napkin rings are Downing’s military rank, his initials, and the year he created them. Especially interesting is the inscription “LIBBY PRISON”, indicating that Downing likely made them during his early imprisonment. He was held at Libby Prison for just a few weeks in 1864, shortly after being captured.

Throughout history, prisoners of war have made beautiful objects under unimaginable conditions, often in an effort to prevent boredom or exchange them for goods or money. For example, French prisoners during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) created intricately carved models of guillotines and British frigates they observed while under captivity. These carvings, like Downing’s napkin rings, are also made of animal bone. Prisoners had to make do with whatever materials were available to them. Elaborate and made of many parts, these French models were likely made by highly trained craftspeople with professional skills. Downing, who served as a lawyer before enlisting, probably didn’t have formal training. In my research, I also discovered beaded snakes that Turkish prisoners of war carefully crafted during the First World War. These beautiful pieces consist of vibrant white, amber, blue, black, and brown beads. Both the French and Turkish prisoners created these objects to be sold to tourists and locals, who bought them as commodities.

Ultimately, the reason behind the things prisoners of war created varied. For Downing, his motivations likely stemmed from a feeling of homesickness, and he chose to create personal objects that were both useful and sentimental. Now part of Preservation Long Island’s collection, Downing’s napkin rings are a powerful reminder of the sacrifices Long Islanders made during the Civil War.

By Tommy Kurita, Collections Intern

Published July 28, 2025

Sources

“Andersonville: The Deadly Confederate Prison Camp.” American Battlefield Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/andersonville-prison. Accessed 26 June 2025.

Bunton, Richard. “The Exploits of Captain Obadiah Jackson Downing (May 1863–May 12, 1864).”

Bleyer, Bill. “2nd N.Y. Cav. Officer’s Memorabilia Returns to Long Island.” The Civil War News, Apr. 2006, pp. 43–43.

Bleyer, Bill. “Civil War History Returns to LI.” Newsday, 7 Nov. 2005, pp. 1–2.

Brown, Fi. “Napoleonic Prisoner of War Crafts.” Word Press, 25 Apr. 2015, rhizomereviews.wordpress.com/2015/04/25/napoleonic-prisoner-of-war-crafts/.

Downing, Robert Cecil. “History of Obadiah Jackson Downing.” 3 Oct. 2005.

Downing, Cecil, Robert. “Was the Union Cavalry’s Captain Obadiah Jackson Downing ‘One of Five’ Who Carried Lincoln’s Dying Body?” Robertjnorton.com, Lincoln ’s Assassination Research Site, 2005, rogerjnorton.com/downing.pdf.

Downing, Robert Cecil. “People Who Have Claimed They Helped Carry Lincoln from Ford’s Theater.” 3 Oct. 2003.

Givens, Benjamin M. The Civil War Society’s Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Wings Books ; Published by Arrangement with the Philip Lief Group, 1997.

Hunt, Harrison, and Bill Bleyer. Long Island and the Civil War: Queens, Nassau and Suffolk Counties during the War between the States. The History Press, 2015.

“Norman Cross Gallery.” Peterborough Museum & Art Gallery, www.peterboroughmuseum.org.uk/norman-cross-gallery-large-print-guide. Accessed 23 July 2025.

“Ottoman Empire Souvenir Snake.” The National WWI Museum and Memorial, www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/spotlight-ottoman-empire-souvenir-snake. Accessed 26 June 2025.

Featured Image: “Libby Prison During the War.” Poster, n.d. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth31146/m1/1/: accessed July 23, 2025), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu, Star of the Republic Museum.