By Tara Cubie, Preservation Director

This April marks a century since F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was first published, casting Long Island’s North Shore into literary legend. Though the novel’s West Egg and East Egg are fictional, most readers—and plenty of realtors—agree they were inspired by Great Neck and Sands Point, two villages facing one another across Manhasset Bay. One hundred years later, Gatsby’s world still lingers in the landscape. Grand estates are listed as “Gatsby-esque,” and visitors seek out the places and personalities that might have sparked Fitzgerald’s imagination.

Where Fitzgerald Lived and Imagined

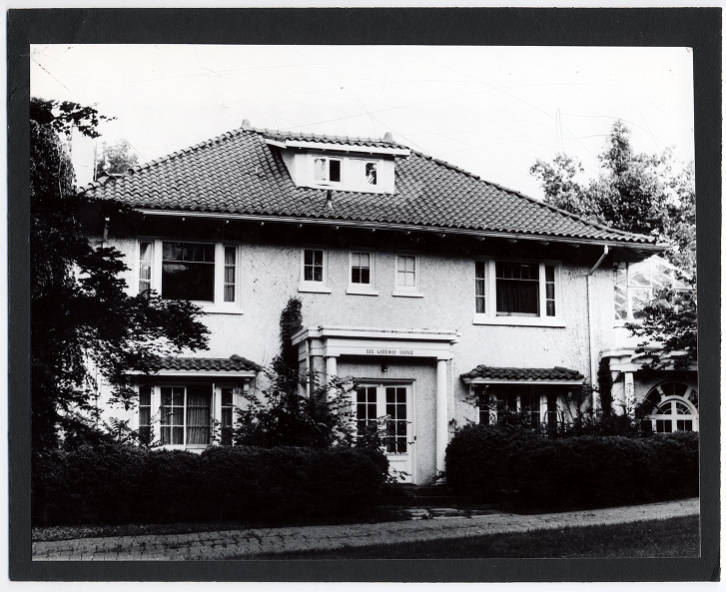

In the fall of 1922, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald moved into a 1918 Mediterranean style house at 6 Gateway Drive in Great Neck. Zelda reportedly called it their “nifty little Babbitt home,” shaded by a weeping willow. It was there, in a room above the garage, that Fitzgerald began writing The Great Gatsby. Though Fitzgerald would finish the book in France two years later, it was during his time on Long Island that the novel began to take shape. Great Neck in the 1920s was a magnet for artists, actors, and socialites—new money rubbing elbows with the established elite. At a rented house on East Shore Road in Great Neck, journalist Herbert Bayard Swope’s house buzzed with Gatsby-level revelry, hosting politicians, writers, and Broadway stars. According to Swope’s wife, the place was “an absolutely seething bordello of interesting people.”

Gatsby’s Mansion: Real Place or Composite Fantasy?

A factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin bead of raw ivy, and marble swimming pool and more than forty acres of land.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

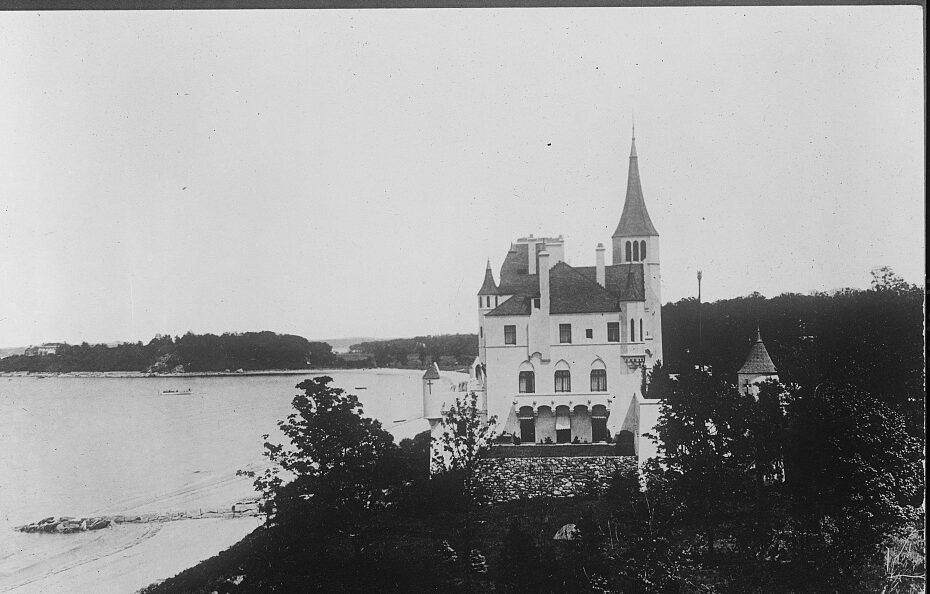

Dozens of properties have claimed the title of Gatsby’s or the Buchanans’ mansions over the years. Some say Land’s End estate in Sands Point—a Colonial Revival estate with sweeping views of the bay, which Herbert Bayard Swope purchased in 1928—was the house that inspired the home of Daisy and Tom Buchanan. The house was demolished in 2011. Gatsby’s grand estate is said to have been inspired by Oheka Castle in Huntington, or Beacon Towers, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont’s gothic fantasy perched on the cliffs of Sands Point. Other inspirations may include Hempstead House and Falaise at Sands Point. With its feudal silhouette, Beacon Towers most closely resembles the novel’s description of Gatsby’s Normandy-inspired palace.

Yet Fitzgerald never confirmed a specific architectural muse. Scholars Raymond and Judith Spinzia suggest the estate was likely an amalgam of local grandeur and Fitzgerald’s memories of Europe. Still, that hasn’t stopped real estate agents from trading on the Gatsby name. In 2024, the 1930s-era Erchless estate in Old Westbury went on the market for $23 million—pitched, of course, as “Gatsby-esque.”

Real People Behind the Fiction

While Gatsby and Daisy remain elusive inventions, Fitzgerald did leave a few clues about the real people who shaped his characters. Scribbled in the margins of his copy of André Malraux’s Man’s Hope are names like “Rumsies + Hitchcocks… Swopes… Goddards… Dwanns.”

These weren’t random notes—they were the people who populated Fitzgerald’s North Shore:

• Charles Cary Rumsey, a Brookville sculptor and polo player married to Mary Harriman

• Tommy Hitchcock Jr., war hero and sportsman from Old Westbury, widely believed to have inspired Tom Buchanan

• Herbert Bayard Swope, whose legendary parties may have seeded Gatsby’s own soirées

• Allan Dwan, a pioneering filmmaker who lived in Great Neck

These were the Fitzgeralds’ social circle while on Long Island, mixing wealth, celebrity, and influence in a way that began to shape Gatsby’s imaginary world.

East Egg, West Egg—or Westport?

For decades, scholars and fans have mapped Fitzgerald’s fictional geography onto Long Island’s real one: West Egg equals Great Neck (the realm of new money), while East Egg stands in for old-money Sands Point, the two separated by Manhasset Bay. But recent research has cast a wider net.

Before moving to Great Neck, Fitzgerald and Zelda spent time in Westport, Connecticut, in 1920—living near the house of millionaire Frederick E. Lewis that bears a striking resemblance to Gatsby’s. Lewis threw celebrity-packed parties at his house that echoed the spectacle thrown by Gatsby—with guests ranging from magician Harry Houdini to great stage stars of the day, such as Ina Claire. In truth, Gatsby’s setting may have been a blend of both locales, tied together by Fitzgerald’s sharp eye for social drama.

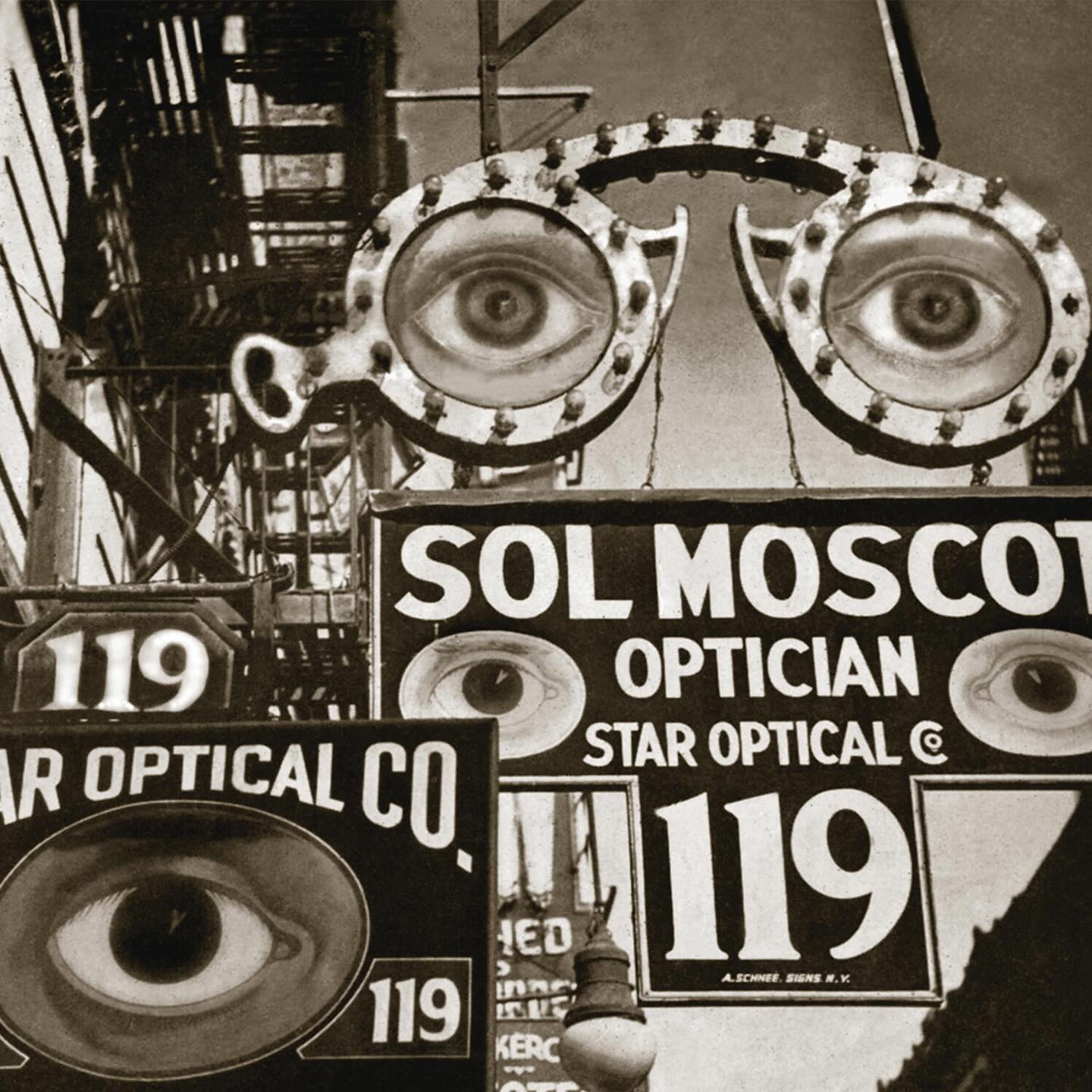

The Valley of Ashes: From Industrial Waste to Public Park

One of the few places Fitzgerald names outright is the “Valley of Ashes”—a desolate expanse between West Egg and Manhattan. In reality, this was a massive ash dump in Queens, operated by the Brooklyn Ash Removal Company. Today, it’s Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, home to the U.S. Open and the Unisphere. As for the iconic billboard of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg’s eyes? Some say it was inspired by vintage ads from Moscot Eyewear, a still-operating Lower East Side institution founded in 1915.

From Page to Screen: Gatsby’s Film Legacy

The Gatsby myth has only grown with each film adaptation. In the 1974 version starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, Rosecliff Mansion in Newport, Rhode Island—modeled after Versailles’s Petit Trianon—stood in for Gatsby’s estate. The ballroom scene, with Gatsby and Daisy dancing beneath a glittering chandelier, was actually filmed at the nearby Marble House, another Gilded Age treasure.

Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation took a different approach, using cutting-edge CGI and stylized visuals to conjure a dazzling, hyperreal Jazz Age. Most of the film was shot in and around Sydney, Australia, but the design team made research trips to Long Island—a visit that helped shape the look and feel of Gatsby’s world in the film.

Beyond the Green Light

We may never find the real Gatsby house, but that’s part of the novel’s magic. Fitzgerald built a world that feels real not because it’s precise, but because it captures the dream life that was the Jazz Age on the North Shore of Long Island. It draws on the rhythms of Long Island life, the tension between old money and new, and the dream of reinvention that still shapes the shoreline.

While The Great Gatsby paints the North Shore as a world of extravagance, moral indifference, and fleeting pleasures, the true history of Long Island’s Gold Coast is far more complex. Yes, there were lavish parties and larger-than-life personalities, but this region was also home to individuals whose contributions extended well beyond the walls of their estates. From presidents and first ladies to military leaders, diplomats, philanthropists, and civic reformers, many North Shore residents played meaningful roles in shaping both local and national history. These are the stories that are missed by the Gatsby mythology. The allure of Gatsby’s mansion may captivate the imagination, but the real legacy of the Gold Coast lies in the people who helped build—and preserve—the cultural and civic fabric of Long Island.

Over the past century, many of the grand estates that inspired F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby have vanished from Long Island’s North Shore. Once numbering over 1,000, very few Gold Coast mansions remain today. Notable losses include Beacon Towers, demolished in 1945, and Inisfada, razed in 2013 despite preservation efforts. These demolitions represent not only the loss of architectural marvels but also the erasure of tangible links to the region’s cultural and literary heritage. The surviving estates—such as Oheka Castle and Hempstead House—now serve as vital touchstones to this storied past.

Many of these historic houses on Long Island have already been lost, and many of the remaining residences are still threatened by development and the cost of maintaining these historic estates. Creative solutions like converting the Pratt Estate into the Webb Institute and the conversion of Oheka Castle into a historic hotel and entertainment venue show that there are creative and preservation minded solutions to these problems, that keep the community at the center. Each estate that disappears takes with it a piece of our collective history—stories, craftsmanship, and cultural significance that cannot be recreated. By bringing more attention to these places and making their histories more visible to the public, we can build greater appreciation for their value. Preserving these landmarks isn’t just about protecting beautiful buildings; it’s about safeguarding the deeper heritage they embody and ensuring that future generations can experience and learn from the real-world echoes of Gatsby’s world.

References

Bruccoli, M. J. (1981). Some sort of epic grandeur: The life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (p. 184). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Diamond, J. (2012, December 25). Where Daisy Buchanan lived. The Paris Review. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2012/12/25/where-daisy-buchanan-lived/

MacKay, R. B., Baker, A. K., & Traynor, C. A. (Eds.). (1997). Long Island Country Houses and their Architects, 1860–1940. W. W. Norton & Company.

Morrison, D. (2009, May 1). Will the real Great Gatsby please stand up? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/will-the-real-great-gatsby-please-stand-up-53360554/

Newland, R. (2015, March 26). The Great Gatsby: Establishing the historical context with primary sources. Teaching with the Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2015/03/the-great-gatsby-establishing-the-historical-context-with-primary-sources/

Spinzia, R. E., & Spinzia, J. A. (1997). Gatsby: Myths and Realities of Long Island’s North Shore Gold Coast. The Nassau County Historical Society Journal, 52, 16–26. Retrieved from https://spinzialongislandestates.com/GATSBY.pdf