By Lauren Brincat, Chief Curator and Director of Collections

It is hard to imagine that throughout the nineteenth century, grand hotels dotted Long Island’s shores. All but gone from the landscape, these fashionable destinations were once refuges from the stresses and unhealthful conditions of urban life—playgrounds for white affluent New Yorkers in search of leisure, sport, and pure ocean breezes. Among the earliest and most famous of these resorts was the Marine Pavilion in Rockaway.[1]

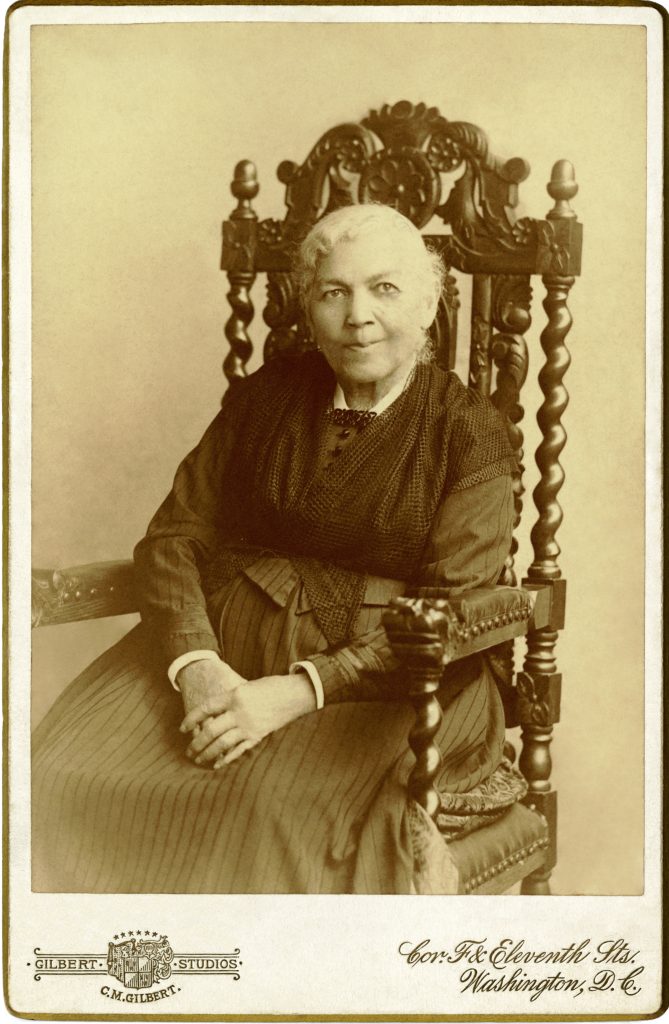

I initially came across the resort while researching the history of tourism on Long Island for our new publication, Promoting Long Island: The Art of Edward Lange, 1870–1889. It can be a surprise, sometimes, the paths research takes you down, and I have to admit, I was a little bit shocked when I came across references to the Marine Pavilion in Harriet Jacobs’s (1813–1897) heart-wrenching autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). I had no idea the famed author had spent any time on Long Island. I needed to learn more and share her story.

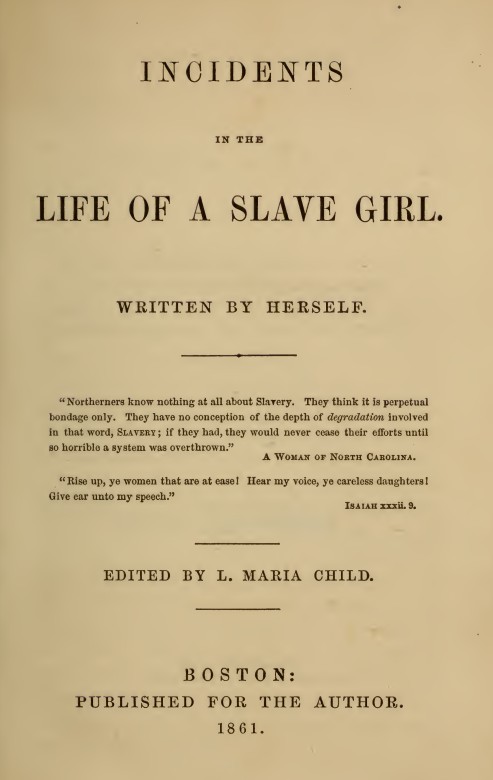

Published in Boston at the outset of the US Civil War and written under the pseudonym “Linda Brent” and edited by Lydia Maria Child (1802–1880), Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is the most widely read antebellum narrative by a formerly enslaved woman and among the most sophisticated of the genre. In the preface Jacobs writes, “I have not written my experiences in order to attract attention to myself; on the contrary, it would have been more pleasant to me to have been silent about my own history . . . I want to add my testimony to that of abler pens to convince the people of the Free States what Slavery really is.” [2]

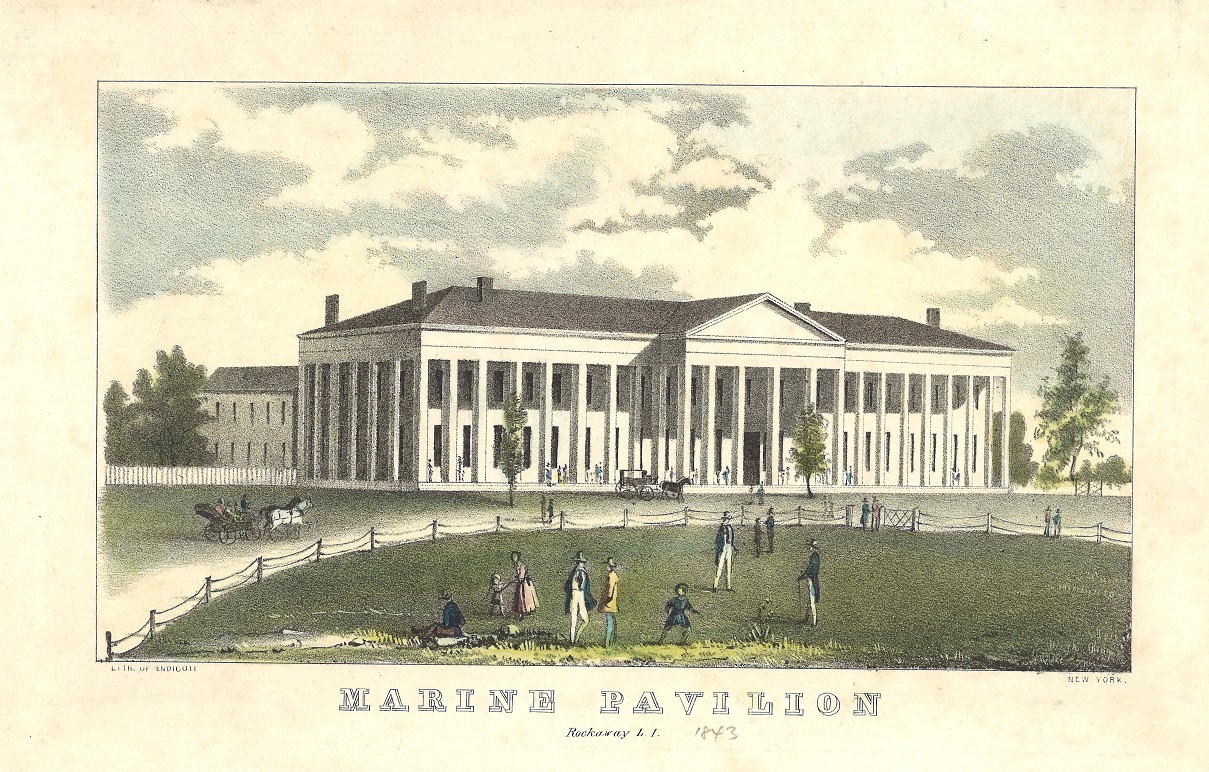

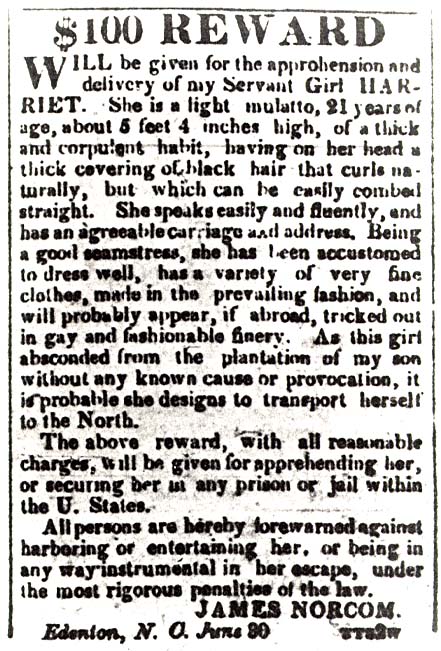

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery around the year 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina, where she survived horrific violence and abuse. In 1842, she made her way to New York City after hiding in a cramped crawlspace at her grandmother’s house for seven years. While legally considered a fugitive from slavery, Jacobs found work as a nurse with popular author Nathaniel Parker Willis (1806–1867) and his wife Mary Stace Willis (1816–1845). In the summer of 1843, she accompanied the couple and their baby Imogen on a trip to the Marine Pavilion in Rockaway. The hotel had opened a decade earlier, and at the time, was one of the grandest in the United States. Designed by prominent architect James Harrison Dakin (1806–1852), the Greek Revival building cost $43,000 to construct and featured two proportionate wings, piazzas, and a 230-foot colonnaded front with a bold pedimented portico overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Across three floors were lodgings for 160 people, a dining room, reading room, and billiards room. French chefs prepared meals for guests and bathing carriages of “the most approved European models” enabled patrons to discreetly and conveniently change into their swimwear before wading into the ocean. [3] Such amenities would not have been accessible to Jacobs, a Black woman employed as a servant to white patrons of the hotel.

The Pavilion was the brainchild of a group of influential New York men who conceived it to function as a summer residence for them and their families while catering to those seeking an escape from the city’s recent cholera epidemic. The completion of the Brooklyn and Jamaica rail line in 1836 eased access to the Marine Pavilion, with multiple stagecoaches each day shuttling visitors to and from the resort and the train station at Jamaica. Situated just twenty miles east of Manhattan, the hotel quickly became a popular destination among the country’s literati, attracting the likes of Washington Irving (1783–1859) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), both close acquaintances of Nathaniel Parker Willis. [4] Preservation Long Island’s lithographic print of the Marine Pavilion, created in 1843 by Endicott and Company, is the only known view of the fashionable resort and shows it the same year Jacobs spent a month there with the Willis family. The halcyon image, likely created to promote the well-heeled establishment, conveys little information to viewers today about the experience of those who were not considered its guests.

An entire chapter of Jacobs’s autobiography is devoted to her experience at the Marine Pavilion. Entitled “Prejudice Against Color,” it offers a striking alternative view of the famed resort and rare firsthand account of the racial tensions that pervaded antebellum New York. On her journey down to Rockaway, she describes witnessing “the same manifestations of that cruel prejudice, which so discourages the feelings, and represses the energies of the colored people.” At the hotel, there were thirty to forty nurses from a “great variety of nations,” but Jacobs was, as she describes, the only one “tinged with the blood of Africa.” [5]

At supper time in the dining room, Jacobs recalls being instructed to stand at the chair of one-year-old Imogen and feed her from behind. Afterwards, she was to remove herself to the kitchen. Jacobs, however, refused and instead took the child back to the room where Willis had their meals sent. After a few days, the white staff rebelled against having to deliver her food while other servants expressed dissatisfaction over not being treated alike. The hotel eventually “concluded to treat [her] well” after it became clear Jacobs was not going to relent, asserting there was no justification for the unequal treatment; the cost for accommodations was the same for both white and non-white servants. Jacobs would end up spending an entire month at Rockaway. [6] For another twenty years, the Marine Pavilion remained a premier destination for wealthy resort-goers until a fire destroyed the edifice along with its furniture and valuable paintings collection on June 25, 1864.[7]

Throughout her time living in the North, Jacobs was continually pursued by her former enslavers and was forced, on multiple occasions, to flee New York in order to evade recapture. Her situation became especially precarious following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which mandated that freedom seekers, like Jacobs, be returned to their enslavers without due process. Two years later, Nathaniel Parker Willis’s second wife, Cornelia Grinnell Willis (1825–1904) purchased her freedom. Jacobs would write her autobiography while working at the Willis’s country estate in the Hudson Valley, encouraged to share her story by Amy Kirby Post (1802–1889), an abolitionist, suffragist, and Quaker originally from Long Island.

Despite Harriet Jacobs’s use of a pseudonym, she garnered notoriety among abolitionist circles for her unflinching yet ultimately triumphant narrative. Writing about Jacobs’s work 160 years after its initial publication, historian Tiya Miles reflects: “as a Black woman addressing white women about issues of utmost sensitivity, as an author articulating the vexed nexus of racialized gender experience, as a woman intent on changing society through her pen, Jacobs was a torchbearer.” [8]