By Lauren Brincat, Curator, Preservation Long Island

The latest addition to Preservation Long Island’s outstanding collection of regional decorative arts is a rare Queen-Anne-style cherrywood eight-day tall clock made in eastern Queens County (now Nassau) around 1785. Upon first glance, its Long Island connection is clear. Engraved on the face of the brass dial is “Willet Hicks/Long Island.” But who was Willet Hicks? As it turns out, he was a lot more interesting than we originally thought.

For those familiar with Long Island history, the Hicks surname is a recognizable one. The Hickses were prominent Quakers whose presence on Long Island dates back to the seventeenth century. Willet Hicks (1765–1845) was the son of Silas Hicks (1737–1782) and Rachel Seaman (1742–1797), who were members of the Westbury Monthly Meeting. Eighteenth-century New York City directories confirm that Hicks was an active clock and watchmaker. As early as 1789, he was operating a business on Queen Street in lower Manhattan. Three years later, he married Mary Matlack (1775–1831), and the couple had two daughters.

The outdated style and rough construction of the clock’s wooden case indicate a rural origin for this piece rather than an urban one. An unknown local joiner, probably from the Hempstead area, likely made the case to house the movement created and assembled by Hicks, who may have used imported English components as well. The use of wooden plugs to cover recessed nails fastening the front frame of the waist section to the sides suggests a relation to other eastern Queens County case pieces that exhibit this same technique, notably, double-paneled blanket chests. It is clear that Hicks created the clock before his arrival in Manhattan in 1789. A pencil inscription behind the hood door suggests the clock descended in the Albertson family, Quakers also from the Westbury-Hempstead area.

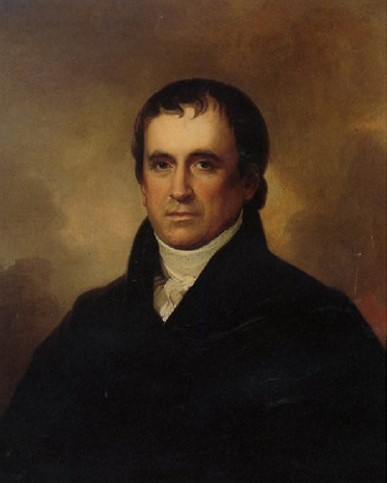

By 1792, Hicks was no longer working as a clockmaker, but instead as a merchant on Pearl Street. He eventually amassed great wealth as the head of the domestic dry-goods firm of Hicks, Lawrence, and Co. In addition to being a businessman, Hicks was also a Quaker preacher. He gained notoriety traveling throughout the United States and England delivering sermons. In Walter Barrets’s 1866 publication The Old Merchants of the New York City he describes Hicks as a “…fine, portly, dignified man; dressed well, and traveled…with his own servants. He spoke often and fluently. He was called the Bishop of the Church, he always had so much attention shown to him…and his appearance was more grand than preachers generally made…”

Willet Hicks was the cousin of renowned Long Island Quaker minister Elias Hicks (1748–1830), whose liberal, controversial doctrines contributed to the first major schism within the Society of Friends in 1827/28. Like his cousin, Elias initially trained as a craftsman (in his case a carpenter) before turning to the ministry. Elias’s followers, who came to be known as Hicksites, viewed the Bible as secondary to the individual cultivation of God’s light within. Willet’s material wealth must have been difficult to reconcile given Elias’s denouncement of the possession of “worldly goods” beyond what was needed to support one’s family. Nevertheless, Willet and Elias preached together and attended Monthly Meetings with another cousin, Edward Hicks (1780–1849), the famed Pennsylvania minister and folk painter. The artist, whose many versions of the “Peaceable Kingdom” frequently commented on the fracture of the Quaker faith, painted Willet’s coach in 1823. Despite being “a little ostentatious,” Willet Hicks was known to be “liberal and kind-hearted.”

One of the more fascinating sidebars of Willet Hicks’s life involves the philosopher, political theorist, and author of Common Sense, Thomas Paine (1737–1807). Hicks and Paine were neighbors in Greenwich Village during the last year of Paine’s life, and the old Quaker minister visited Paine daily during his final illness. Thomas Paine, famously a Deist (although he never self-identified as one), was raised a Quaker and hoped that Hicks could help facilitate his internment in the Quaker burying ground. Paine’s request was ultimately denied, and Hicks was one of the few people present at Paine’s unceremonious burial at his farm in New Rochelle.

Paine had fallen out of public favor for the views he expressed in The Age of Reason (published in two parts in 1794 and 1795), which challenged institutionalized religion and the legitimacy of the Bible. Members of the Society of Friends frequently pestered Hicks about Paine’s beliefs, inquiring whether or not the essayist recanted his anti-Christian views as he neared death. In one interview, Hicks proclaimed: “You cannot conceive what a deal of trouble I had…I could have had any sums if I would have said anything against Thomas Paine, or if I would even have consented to remain silent.” Hicks concluded by saying: “He was a good man, an honest man.”

With the Panic of 1837, the firm of Hicks, Lawrence, and Co. broke apart, leaving Hicks in financial straits and ending his “usefulness as a Quaker preacher.” He lived the remainder of his life under the roof of his daughter, Martha, and his son-in-law, Dr. John Cummings Cheesman, a New York City physician. Despite Willet Hicks’s immediate connection to influential Quaker leaders and important historical figures, he has been all but lost from historical memory. Willet Hicks’s tall-case clock reminds us of his story, of Long Island’s vibrant decorative arts heritage, and of the region’s importance to the history of Quakerism in America. It is objects like these that allow Preservation Long Island to share and preserve Long Island’s complex history and cultural heritage in new and exciting ways.