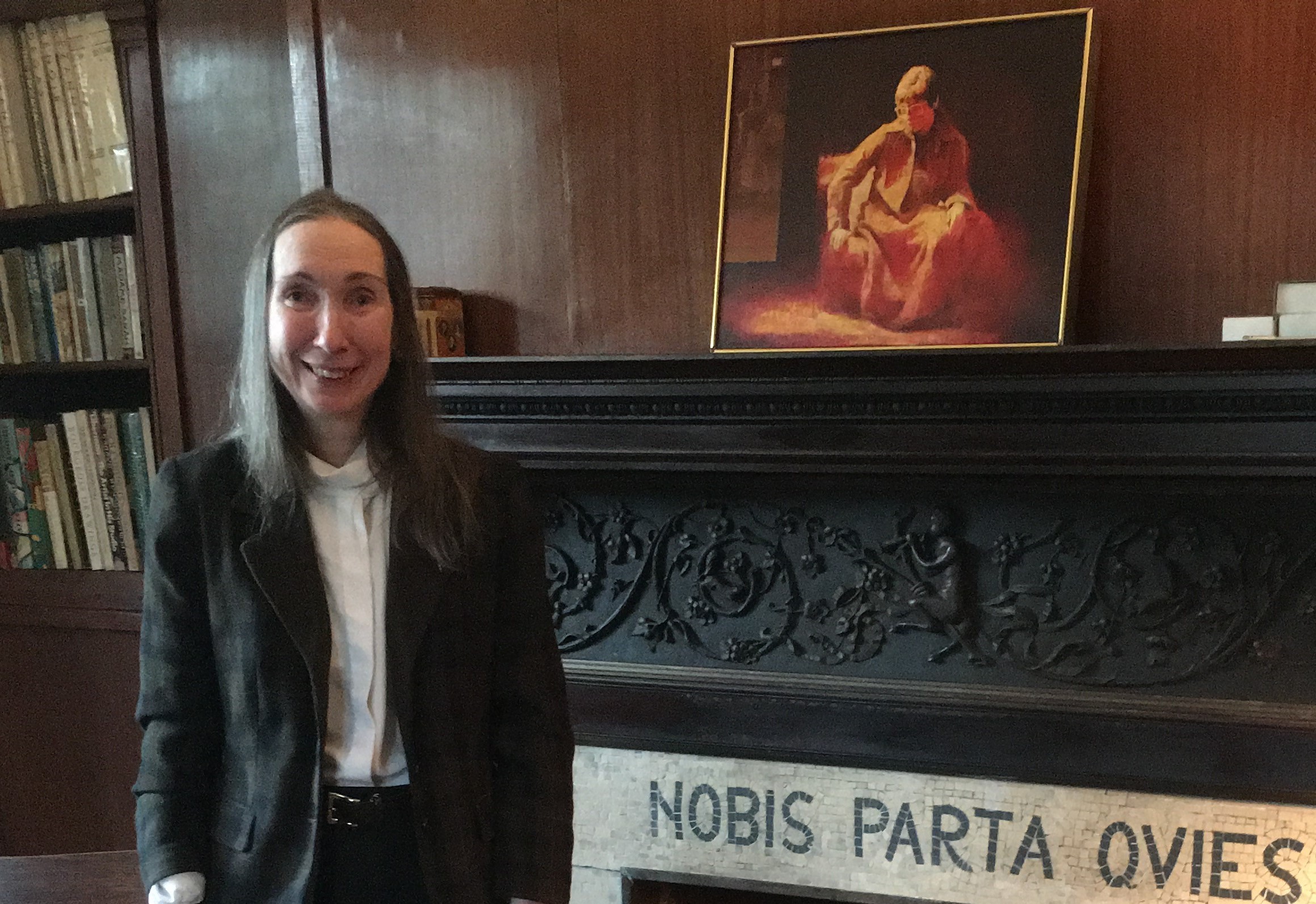

We are pleased to welcome as our guest author Corey Geske, independent historian, who, in 2017, identified the world-famous architect of Owl Hill at Fort Salonga, and the national prominence of the man who commissioned him. Her discoveries transformed an ‘old house’ into a National Register Eligible property by 2021, with unique credentials supporting its acquisition by Suffolk County as a 27-acre park and museum in 2024. Photo Credit: Corey Geske, Owl Hill, November 2017.

By Corey Geske

You’ll find my name linked to discoveries from Grand Rapids, Michigan to Boston, Massachusetts, of people, places, and paintings on museum walls for which and for whom, I’ve documented forgotten, or overlooked histories that deserved to be correctly identified. The results have provided a better understanding of our heritage to promote eye-opening cultural enrichment going forward.

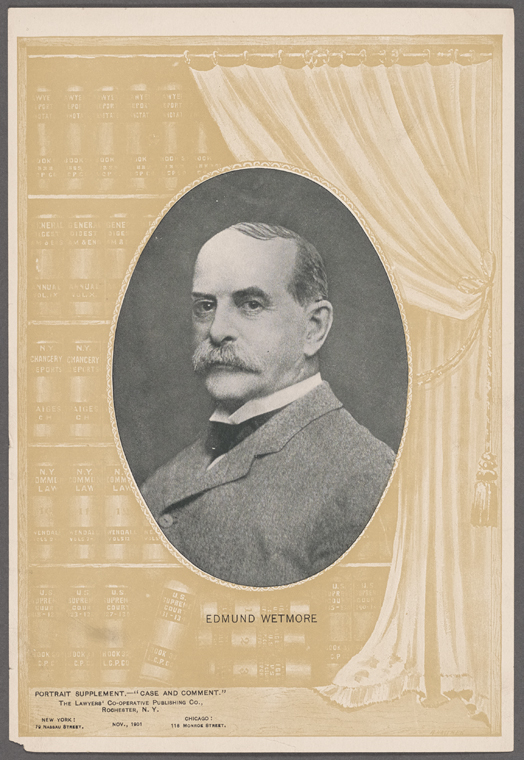

As an independent volunteer historian, in 2017, I discovered that the estate named Owl Hill at Fort Salonga was designed by world-famous architect Henry Killam Murphy (1877-1954) commissioned in 1907 by the nationally renowned patent attorney Edmund Wetmore, Esq. (1838-1918). Though their connections to Fort Salonga had been forgotten until that moment, each man stands as a significant figure, nationally and internationally, establishing Owl Hill as Eligible for the New York State and National Registers of Historic Places in 2021. My discoveries about this inspiring place in the township of Smithtown, were first published in The Smithtown News in 2019, and many of the facts therein are incorporated in this blog.[1]

By its dedication to the Suffolk County Historic Trust in 2024, Owl Hill at Fort Salonga enters the future as a park and museum under the auspices of the Suffolk County Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation. The initiative to save Owl Hill was made possible through the advocacy efforts of the office of Suffolk County Legislator Robert Trotta, the Preservation League of New York State, and the Society of Architectural Historians in communication with this writer, Corey Geske; with the support of the Suffolk County Department of Parks, the Fort Salonga Association, Preservation Long Island, and Suffolk County Executive Edward P. Romaine.

We can best face the problems of the Nation’s present if we know something of the Nation’s past.

President Theodore Roosevelt to Edmund Wetmore, Esq.,

President, Sons of the Revolution, November 3, 1907.[2]

I first became aware of Owl Hill when reading The Smithtown News issue of July 7, 2016, wherein an editorial by David Ambro speaking to the need to save Owl Hill, appeared directly across from an historic preservation piece I’d written for the endangered eighteenth-century Mary Woodhull Arthur House, both buildings illustrated on facing pages.[4] Coincidentally, the name of William Arthur, who built the house in 1752 on what is today’s West Main Street, Smithtown, is that of the man who owned land in Fort Salonga where the British built their Revolutionary War Fort Slongo, key to historian Edmund Wetmore’s choice to live in Fort Salonga, the location of Owl Hill.

Murphy’s proteges lead to the master architect

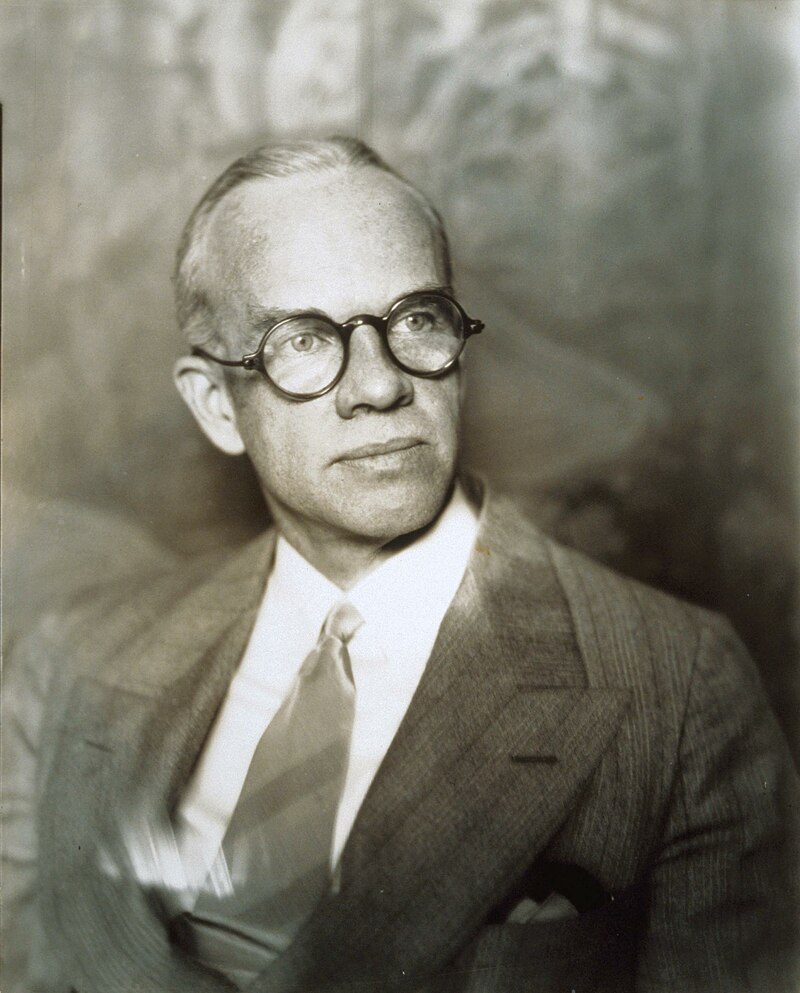

To preserve the Arthur House, I researched and formally proposed a National Register Historic District for the surrounding downtown area of Smithtown in 2017;[5] thereafter preparing reports for eligibility determinations and successful National Register (NR) nominations per place to launch the NR District and generate grants and benefits available to owners of NR properties. Notably added to the Register, was the Byzantine Catholic Church of the Resurrection originally built in 1929 as St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church. I documented the Tudor Revival church as designed by Henry J. McGill (1890-1953) and Talbot F. Hamlin (1889-1956) by locating their drawings in the Avery Architectural Library at Columbia University, where Hamlin would become chief Librarian.[6] McGill and Hamlin were previously Murphy’s proteges and then partners in his New York City architectural practice Murphy, McGill and Hamlin (1921-1924), which led to identifying their mentor’s earlier work at Owl Hill.[7]

My journey of advocacy for the Fort Salonga estate’s preservation began more than seven years ago when an East Setauket-based newspaper reporter called me shortly before going to press requesting a comment on Owl Hill. A quick review of the town’s historic inventory of 1978 recorded no architect, but the design and siting of the house indicated to me a well-schooled architect, so I commented that: “Owl Hill is another example of beautiful architecture in Smithtown for which the architect, to my knowledge, is as yet unknown … This is the kind of house that deserves that kind of research attention because it’s so special with regards to interior detail and its location, built high on the hills of Fort Salonga.”[8] That proved to be true.

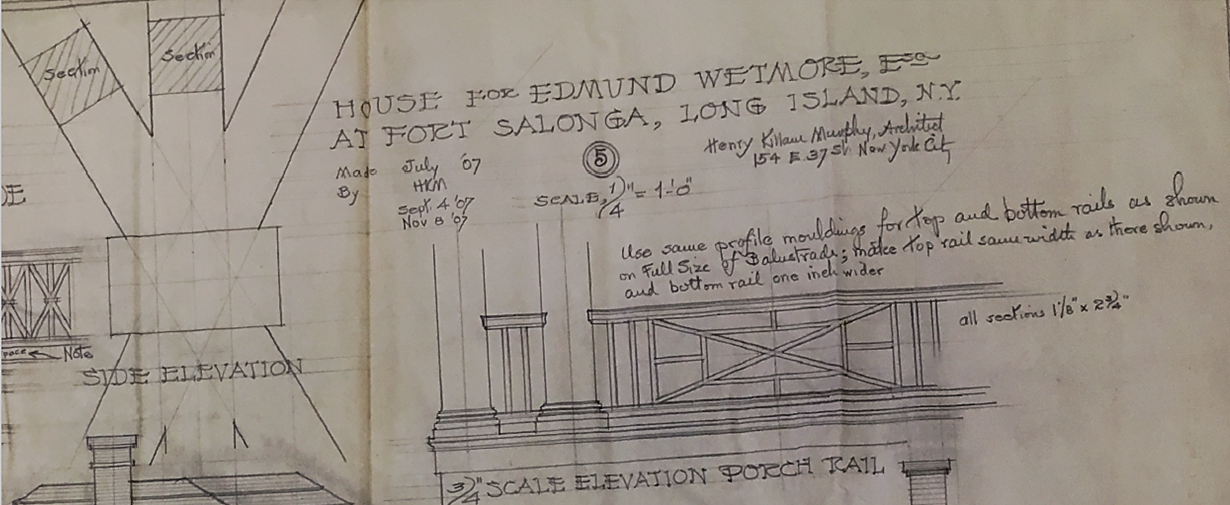

Researching McGill and Hamlin, I’d studied the landmark biography of Henry Killam Murphy by Jeffrey W. Cody, Ph.D., and recalled a footnote citing a letter by Murphy about an [unidentified] house in “Northport” [Fort Salonga actually] that Murphy was designing for an Edmund Wetmore.[9] Based on that recollection, I launched a search of Murphy’s immediately accessible papers at Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library. Though the collection’s Finding Aid catalog then listed no Wetmore commission and the library was under renovation, within a week of the reporter’s phone call, intrepid archivists were braving tarps to pull the necessary boxes in the Henry Killam Murphy Papers, I believed could confirm Murphy designed Owl Hill. The first drawing to appear was labeled “Mr. Wetmore’s sketch of desk for his Library, Oct. 16, ’07,” and Owl Hill had a remarkable library – the clues were adding up. Then, a drawing of a main staircase came to light. It was Owl Hill’s stairway.

As days passed, drawings and a blueprint were found of the country home now called Owl Hill designed by world-class architect Henry Killam Murphy. Also coming to light, was Murphy’s Account Book of Architectural Commissions revealing that he received the commission for the home following a letter received on April 29, 1907 from his mother-in-law’s “old friend,” Helen Howland Wetmore, Edmund’s wife. According to Murphy, he visited the Wetmores at Fort Salonga on May 5, 1907 and “found they had 200 acres of magnificent land, on which we picked out definitely a site and I laid out a 40’ x 50’ main house… I also indicated proper entrance at angle of two parts instead of at end of main house… After lunch I sketched a 1st and 2d floor plan based on… conditions of site, which both Mr. and Mrs. Wetmore liked very much… Mr. Wetmore asked me to go ahead and draw out 1/8” scale plans on basis of my sketch;” on May 18, Murphy again visited them at Fort Salonga, “and they were so much pleased with plans they said go ahead.”[10]

Murphy’s account book narrative revealed that, historically, the estate was entered via a private drive at Fort Salonga Road (Route 25A), with the front entrance approach appearing as shown in his drawing of the “House For Edmund Wetmore, Esq.” The original drive went past no longer extant stables, greenhouses, outbuildings, and an older house, near a freshwater pond at the headwaters of Sunken Meadow Creek. Due to subdivisions that demolished the stables, etc., this approach was changed, so that today’s often photographed façade perspective, welcoming visitors, is the southeast elevation, with paired squared columns, that wraps around to the northeast elevation that fronted the original entrance drive.

Work was begun about August 1, 1907 by Nesconset/Smithtown builder Clarence A. Conklin, specially requested by Wetmore, possibly on the recommendation of St. James architect Lawrence Smith Butler (1875-1954), a descendant of town founder Richard ‘Bull’ Smith. Butler was a member of the Harvard Club (New York City) that Wetmore had served as President. Butler was probably acquainted with Murphy, both having studied in Paris the previous year about the time Butler asked Charles Cary Rumsey to sculpt the Smithtown Bull, which appears to have carried symbolism, in addition to the ‘Bull Smith’ legend, that honors the more than fifty interior designers and architects, including Murphy, and also McGill and Hamlin, who worked or lived in the township during the Butler era through the 1940s.[11]

In the autumn of 1907, Murphy employed M.F. Oliver, to draft details of the main staircase. Oliver was then a partner in the firm Ford, Stewart and Oliver, joined that year by Butler, which in 1908 became Ford, Butler and Oliver, architects of Smithtown’s Town Hall and Library, each built in 1912 and located like ‘bookends’ at the west and east ends of modern Smithtown’s Main Street to respectively house the Town Clerk’s extant (since 1715) records, and anticipated local historical collections and papers.

Jeffrey W. Cody, Murphy’s biographer, and then Senior Project Specialist in the Building and Sites Department of the Getty Conservation Institute, was thrilled to learn of my discovery of a home designed by Murphy, clued by a footnote in his book. He expressed how meaningful it is to preserve such a newly discovered place “for people to understand that incredibly important part of Smithtown history” represented at Owl Hill, which “epitomizes that period of American history,” when highly skilled architects like Murphy were in the right place at the right time, achieving their potential “on the coattails of the Golden Age” at Long Island’s ‘Gold Coast’ estates.[12]

Owl Hill on the North Shore complements the historic estates built and restored on Long Island’s South Shore, also dedicated to the Suffolk County Historic Trust, including ‘Wereholme,’ the ca. 1917 house inspired by a French chateau and designed by world famous architect Grosvenor Atterbury, at the Scully Estate, Islip. And, in Bay Shore, there is the historic Sagtikos Manor built in 1692, and already enlarged when George Washington slept there on his 1790 tour of Long Island. In 1902, owner Frederic Diodati Thompson (1850-1906), hired Sayville architect Isaac H. Green Jr. to build two additions. Since 1877, Thompson had been a Life Member and Member of the Board of Trustees of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, along with fellow member (since 1888) Frederick Samuel Tallmadge (1824-1904), the second President (1884-1904) of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York until his death.[13] Tallmadge also had been a member of the Suffolk County Historical Society, and following his death, Wetmore delivered an extensive address to the Society on “The Puritans” in 1905,[14] and then, ca. 1906, Wetmore moved to Fort Salonga in Suffolk County.

Tallmadge was the grandson of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge (1754-1835), the head of intelligence for the Culper Spy Ring, who planned the successful American crossing of Long Island Sound to achieve victory, October 3, 1781, at the British Fort Slongo that would give the hamlet of Fort Salonga its name. The Colonel’s recounting of the battle was published in the Memoir of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge (1858), based on the original manuscript inherited by his grandson Frederick S. Tallmadge. The Memoir was reprinted by the Sons of the Revolution in New York State, in November 1904, by which time Wetmore had succeeded Frederick S. Tallmadge as President of the Sons. The 1904 Sons’ reprint included a map of Col Tallmadge’s “Exploits,” with “Ft. Slongo” prominently labeled on the North Shore of Long Island, and Culper Spy correspondence from Tallmadge’s network. Owning his grandfather’s papers and memoir, given to the Fraunces Tavern® Museum in New York City, that would open to the public in December 1907, Frederick S. Tallmadge likely introduced Wetmore to Fort Salonga’s Revolutionary War history.

As the next President of the Sons, Wetmore ensured the fraternal organization completed Frederick S. Tallmadge’s plan to publish his grandfather’s Memoir, and continued the Sons campaign, begun by Tallmadge, to save and restore Fraunces Tavern that was General George Washington’s headquarters and the place where the General bid farewell to his officers at the conclusion of the American Revolution.

The only record of Washington’s farewell to his officers on December 4, 1783, and his words, “With a heart full of love and gratitude, I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable,” is in the original handwritten Memoir of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge. It is now at the Fraunces Tavern® Museum[15] restored and opened to the public on December 4, 1907, the anniversary day of Washington’s farewell, and the same year Wetmore commissioned Murphy to build Owl Hill at Fort Salonga. The restored Fraunces Tavern was dedicated to Frederick S. Tallmadge, who on his deathbed had signed the papers to purchase it, and by his bequest ensured its restoration. Based on the Sons’ historic effort, Wetmore appears to have hoped for future commemoration of American Revolutionary War history for Fort Salonga at the home and Library he built, now Owl Hill.

Edmund Wetmore was well aware of the historic importance of the place he chose to build his home, a four-minute drive from the site of the battle of Fort Slongo that resulted in only one American being wounded, Sgt. Elijah Churchill, and Washington personally awarding him America’s oldest military award, the first military honor to an enlisted soldier in the Continental Army, the ‘Badge of Merit.’ Only awarded at the close of the Revolution, it would be reestablished in 1932 on Washington’s 200th Birthday, as the Purple Heart.

One of Murphy’s earliest documented designs in the world

From substantial brick piers beneath the library floor to support the weight of volumes, to the skylight in the attic, Owl Hill is a prescient example of Murphy’s work ethic practiced worldwide adapting architectural design to his client’s interests, within the didactic setting of the surrounding area, fully appreciating that to this day, Long Island Sound can still be seen from the roof accessed by the skylight. For Edmund Wetmore’s house at Fort Salonga, that became Owl Hill, Murphy’s vision is fully delineated upon the master architect’s drawings. Owl Hill is now one of the earliest documented designs in the world, by Murphy.

What makes Owl Hill particularly special is the fact it represents one of Murphy’s rare independent designs when he first founded his firm in 1906-1907, before establishing a partnership in 1908 (until 1921) with Yale instructor, Richard Henry Dana (1879-1933), building in the Northeastern United States. Notably, the library at Owl Hill was perhaps the first and earliest extant that Murphy ever designed, and designed solo, in a career focused on building numerous university libraries, academies, faculty homes and parish houses, mostly in Connecticut and New York around his alma mater, Yale, and also at the College of New Rochelle. About 1914, Murphy and Dana were asked to design and oversee building for ‘Yale-in-China,’ a program that provided medical training, hospitals and educational facilities. Murphy would build fourteen universities and colleges in Japan, Korea, and China (1914-1935), where he designed the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, in 1919. There he has been honored with a life-size statue in gold, showing the architect at work with rolled plans in hand.

Murphy published his treatise “The Adaptation of Chinese Architecture” in 1926. By 1928, his practice of “adaptive architecture” incorporating surrounding features into his designs, drew the attention of Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, who appointed Murphy as advisor to the National Government of the Republic of China and architect for planning the capital city at Nanking (now Nanjing). Murphy is internationally recognized for having trained, or influenced, several of the ‘first generation’ (diyidai) of Chinese architects.

Murphy’s Adaptive Architecture for Early New York Historic Preservationist Edmund Wetmore

Henry K. Murphy’s universally appreciated “adaptive architecture” closely attuned to the interests of his clients, and the topography, climate, and history of the surroundings of his projects, is reflected by architectural details at Owl Hill, evidencing Wetmore’s leadership in the effort to restore Fraunces Tavern.

Twelve over twelve windows and paneling in the dining room at Owl Hill, follow the example of the Pearl Street façade at the restored Fraunces Tavern, and its Long Room where Washington bid farewell to his officers. For the porch balustrade at Fort Salonga, Murphy visually floated and framed the X in a rectangle design of the Tavern’s old rooftop guardrail seen in an 1883 etching that Wetmore likely had studied, and apparently preferred, compared to the Tavern’s post-restoration vertical baluster guardrail that ran along a squared platform supported by the four upward sloping sides of the Tavern’s hipped roof. [16] Murphy adapted the platform concept to the Wetmores’ hipped roof, adding a skylight accessing a view of Long Island Sound, in addition to views from the porch mentioned in local newspapers of the 1930s and 1950s. The effect was a timeless perspective on the crossing of Long Island Sound for the American attack on Fort Slongo, landmarking Fort Salonga’s importance during the Revolutionary War.

The historic X in a rectangle porch rail design seen in the Tavern’s 1883 etching would have been available to Murphy because it also headed a New York Times article reporting the Tavern’s restoration was largely complete by March 17, 1907, [17] about a month before Mrs. Wetmore sent her inquiry to Murphy, and the Wetmores embarked on building their own home giving a sense of place to Wetmore’s interest in commemorating Fort Salonga history.

Murphy’s younger colleague Talbot F. Hamlin (see earlier), became a noted architectural historian, Librarian (1934-1945) of the Avery Architectural Library at Columbia University, Pulitzer Prize winner, and active member of the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH). In 1942, Hamlin developed a list of historic buildings built in Manhattan before 1865, that would lead to guidelines for designations by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Fraunces Tavern, believed to be the oldest building in New York, also one of the first preserved (during the leadership of Sons’ President Edmund Wetmore), would be one of New York City’s first landmarks, designated in 1965; and in 1975, the Fraunces Tavern block was saved as a historic district, with the help of The New York Landmarks Conservancy.[18]

Wetmore’s Appreciation of Libraries and Education

Patent attorney and President of the American Bar Association (1900-1901) and the Bar Association of the City of New York (1908-1909) that he founded in 1869, Edmund Wetmore, Esq. had attended Harvard on a Shattuck Scholarship when a rare volume of Virgil’s Aeneid was gifted to the University. It included a verse that Wetmore asked Murphy to inscribe upon his library mantle at Owl Hill. Appreciating the Greek and Roman classics as a source of inspiration and ‘joy,’ Wetmore is remembered by friends as carrying a volume with him on journeys, that included the business of the courts in Washington, D.C.[19] He also tried his hand at poetry, penning “The Cocked Hat,” about the Revolutionary War era tri-cornered hat, “the symbol of days when brave souls were tried,” that continues to be reprinted in the annual journals for the Sons’ celebration of Washington’s Birthday each February.

Wetmore served with Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) on the Harvard Board of Overseers for years; was consulted by President Roosevelt (1901-1909) on various matters “of importance;” and invited the President to the Sons’ events at Fraunces Tavern.[20] Representing the Sons of the American Revolution in 1911, Edmund Wetmore and his wife Helen attended events at St. John’s College and the Naval Academy in Annapolis, along with the next President (1909-1913) and Mrs. William Howard Taft, the French ambassador and numerous dignitaries, commemorating the participation of French soldiers and sailors in the American Revolution, as America’s ally.[21]

Edmund Wetmore’s interest in honoring an American ally of the Revolutionary War echoed his ancestry. He was a member of the Sons because he was the great-grandson of the missionary Rev. Samuel Kirkland (1741-1808),[22] Chaplain to the American army at Fort Schuyler during the Revolution, and the patriot responsible for securing an alliance with “The First Allies,” the Oneida Nation of the Six Nation Confederacy. With President George Washington’s support for his proposal, Kirkland founded Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 (Hamilton College, chartered 1812), to educate Native Americans; Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, agreed to be a trustee. There the Oneida Chief Skenandoa asked to be buried in the college campus cemetery near his friend the reverend and his family.[23]

Named after Alexander Hamilton, the Hamilton-Oneida Academy’s cornerstone was laid in 1794 by General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who during the Revolution established manuals of discipline ensuring that military drilling conducted at Valley Forge and thereafter turned the Continental Army into a fighting force to be reckoned with. Von Steuben’s sword was inherited by Edmund Wetmore, by way of a chain of possession from the General to his aide-de-camp and executor of his will, then to his attorney Judge Morris S. Miller, the law partner of Edmund Wetmore’s father (Edmund A. Wetmore was twice Mayor of Utica). Wetmore and his sister, would present the sword to the Oneida Historical Society in 1897.[24]

Wetmore was President of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York (1904-1914) and the Sons General Society (1911-1915), when three years after Owl Hill was built, and perhaps inspired by Washington’s ‘Badge of Merit’ (later the ‘Purple Heart’) awarded for action at Fort Slongo, his brainchild the Knox Trophy was named after Washington’s chief of artillery, General Henry Knox. The trophy was first presented, October 8, 1910 by the Sons, and is now the oldest continuously presented award at West Point, given by the Sons of the Revolution, annually to the cadet with the highest rating for military efficiency at the United States Military Academy.

In 1912, as General President of the Sons, Wetmore delivered an address, “The birth of the Constitution,” framing values applicable to historic buildings, philosophizing that when, “it seems as if some hurricane; of short-lived popular passion would sweep us from our path, we have only the more resolutely to follow the road that our fathers trod before us, to fix our eyes on the landmarks that have stood for ages, to remember our glorious past, and then whatever storms may surround us, we may rest tranquil in the faith that as we follow in the way of our fathers, the God of our fathers will not forsake us.”[25]

Garden Club Destination

Edmund Wetmore was interested in horticulture with a published reputation for large tree plantings in 1893 of silver, sugar, and weeping silver maples, poplars, and lindens at his Glen Cove estate prior to building in 1907 at Fort Salonga;[26] and his wife Helen Howland Wetmore (d. 1924), a patroness at Harvard fund-raising events, was interested in ornithology, recognized in a New England publication of 1911 as from “Fort Salonga, L.I., N.Y.”[27]

The Wetmores’ country house designed by Murphy became known as ‘Hickory Hill’ during the 1920s and 1930s under the care of its next owner, Ancel J. Brower (1870-1943), President of the Isaac H. Blanchard Co., and elected President of the Printer’s League of New York in 1920.[28] Society columns refer to the “beautiful azalea collection,” and note that during society events, tables were placed on the “porch overlooking the lovely gardens of the estate.”[29] At his passing, the community remembered that, “Mr. Brower developed his hobby of horticulture at Hickory Hill, Fort Salonga,” adding that he “became particularly well-known as the developer of many new hybrid rhododendrons and azaleas,” appreciating that annually, “when these shrubs were in bloom, he opened his beautiful estate to Garden Clubs and other flower lovers,” making “Hickory Hill one of the show places of Long Island, and for many years his family took a great interest in social and philanthropic circles.“[30]

Journeys of Discovery

In 2017, as the sun was setting on more than a century of family-style ownership at Owl Hill, I was thankful for having been invited to share my discoveries of Murphy and Wetmore, with the family who’d lived there for more than sixty years, and had the opportunity to see the house, much as I believe first owners Edmund and Helen Howland Wetmore could have furnished their home. On those visits, I shared Murphy’s notes and drawings with the family, and heard of their past proactive restoration work that has preserved the realization of Murphy’s detailed drawings from more than a century ago.

I also learned that they, the family connected to the estate for half a century, had named Owl Hill just that because of the owl motif frequently found in the home’s furnishings. Historically seen on a stack of books and associated with libraries and academies, the owl was appropriate to the emphasis upon the Library at Edmund Wetmore’s home, and was a symbol of learning attached to Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, law, the sciences, and the arts, also known as a champion of “just causes,” and military strategy. The owl motif at the Fort Salonga estate, strongly suggests the influence of attorney Edmund Wetmore in his defense of patents, and his interest in preserving the memory of the American victory at Fort Slongo, based on the planning strategy of Washington’s chief of intelligence, Col. Benjamin Tallmadge.

This volunteer historian is not the first to have made a journey of discovery because of Owl Hill. And, now because of Suffolk County’s acquisition, the public will experience an amazingly inspiring place where the descriptives ‘poet’s walk,’ and inspirational ‘think-tank,” are demonstrated by its history, and experienced from inside the mansion’s library to its surrounding acreage of open space planted in a designed landscape of trees, rhododendrons, and azaleas that a century ago established the estate as a must-see for garden clubs, and now for all Long Islanders and visitors because Owl Hill is dedicated to the Suffolk County Historic Trust.

Murphy indicated an “INSCRIPTION” on the blueprint for the northwest parlor mantel (where it may yet be found with future study), but Wetmore chose the Library mantel as the place for an inscription inlaid in mosaic with a wood surround equating to a scrolled chapter headpiece in an old book. From Book III, Line 495 of Virgil’s Aeneid, of which a special edition was gifted to Harvard when Wetmore was a scholarship student, the mantel inscription reads NOBIS PARTA QUIES (“To us tranquility is secured”), attesting to the renowned attorney’s case that Owl Hill inspires.

The Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press publication Places of Invention examines places like Silicon Valley, California known for electronics and hi-tech innovation, as well Hartford, Connecticut during the late 1800s where “Yankee ingenuity” spurred inventions and patents, to show, according to the Smithsonian’s advertisement, that “the history of invention can be a transformative lens for understanding local history and cultivating creativity on scales of place ranging from the personal to the national and beyond.”[31] In that spirit of invention, here on Long Island, overlooked until now, is a place called Owl Hill owned by those who defended patents and patented inventions.

Among numerous patents Wetmore defended was that for Henry Ford’s gasoline powered engine. Nearly fifty years later, he was remembered in Fort Salonga as “lawyer for the late Henry Ford,”[32] which may have been one more reason why, future Auto Hall of Famer Fred Wagner, who knew Ford, would buy land beginning in 1910, to build his home in Smithtown.[33] Wetmore also defended the patents of Nikola Tesla (1856-1943),[34] who explored electric power and is considered the creator of a new electric age.

Yardney’s many inventions are associated with broad patterns of our history, benefiting science, medicine, and the arts. The New York Times reported that Yardney “studied at the Sorbonne, the Ecole Polytechnique de Caens and the Ecole Superieure de Electricite de Paris.”[36] He and his company, located during the 1950s in New York City, developed unique battery patents that powered space exploration in the early days of NASA’s Mercury, and Gemini programs, and the landing of man on the moon in the 1969 Apollo mission. After his death, the company continues today, powering NASA’s Curiosity rover exploring Mars since 2012, and furthering the Orion Project, NASA’s next planned ship for manned interstellar travel.

Yardney’s work advancing battery technology literally empowered his collaborative invention for an electric car in the 1950s; and while promoted for its climate awareness in the Congressional Record in the 1960s,[37] the “Yardney Electric Car” was photographed in 1967 before the Capitol building. Two years later, Yardney applied for, and then received a patent for a hybrid engine, years ahead of his time.

His patents included medical advancements, notably in hearing aid technology improving everyday life.[38] The Yardney name is on a battery remaining on the Moon’s ‘Tranquility Base’ where humankind first walked on a celestial body other than earth, and it’s a reminder of the mantel inscription at Owl Hill — NOBIS PARTA QUIES (“To us tranquility is secured”).

Owl Hill was Yardney’s “think-tank;” its spacious library looking out on his wooden seat beside an electric pole connecting him to telephone calls from the outside world, overlooked the natural and designed landscape, woodlands, and wildlife refuge for owls and deer, in this place that inspires new paths of humanitarian effort.

©Author Corey Phelon Geske retains copyright to this article.

January 15, 2025