We are pleased to welcome to the blog this summer’s Gardiner Young Scholar, Genevieve Barbee.

This summer, Genevieve, an undergraduate student at Cornell University, worked closely with our Preservation Director, Tara Cubie, to update the existing Endangered Historic Places list and contributed to the development of the new list, which will be released in early December. In this blog post, she explores the story of the Peter Crippen House, a site added to the Endangered Historic Places list in 2021, and highlights its ongoing significance within our region’s preservation landscape.

In the video below, Genevieve discusses her work with us and what she learned during her time as a Gardiner Young Scholar.

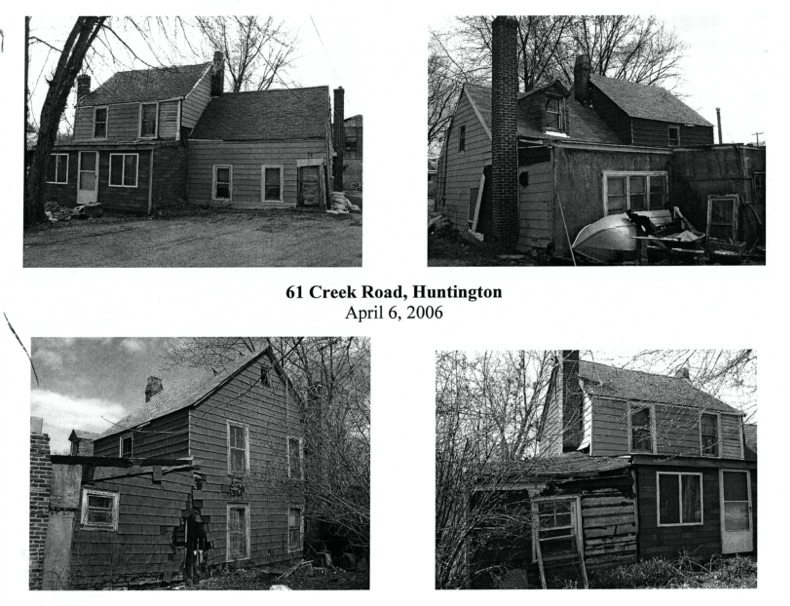

The Peter Crippen House does not quietly decay. It leans, it splinters, it collapses in slow motion—a stark and unflinching reminder of what is lost when history is left untended. Once a modest but vital center of community life in Halesite, New York, this mid-19th century dwelling now stands in ruin, its roofline folded in on itself and clapboards weathered to bare wood. Even in this state, the house commands attention. It is the kind of building that draws you to a halt—not for grandeur, but for the unmistakable sense that here, something important happened.

Peter Crippen was a free Black man navigating an America still entangled in the legacies of enslavement. Born in the early nineteenth century, he came of age in a state that had legally abolished slavery but preserved the architecture of inequality. In Halesite, a maritime hamlet of shipbuilding and oystering, Crippen secured his place as both property owner and civic leader. He helped to found the Bethel AME Church in Huntington, which would become not only a sanctuary of worship but a citadel of activism for the region’s Black residents.

The house itself was unpretentious in scale, practical in plan. Timber-framed, board-clad, its steep roof pitched against Atlantic storms, it embodied the resilience of its builder. That it endured into the twenty-first century is in itself remarkable. Yet endurance has now given way to fragility. The north section has collapsed; the chimney lingers precariously above a tangle of rafters; vines creep deliberately through the skeleton of the frame. Patches of mismatched siding—green clapboards interspersed with weathered white planks—register the years of piecemeal repair, a palimpsest of care and neglect. Even in ruin, the structure offers rare physical testimony of African American domestic architecture in nineteenth-century Long Island, a category of heritage disproportionately effaced by demolition, indifference, and redevelopment.

Its decline is not a neutral consequence of time, but a symptom of a larger neglect. Too often, the built legacies of African American life have been undervalued—sidelined in preservation priorities, dismissed in cultural hierarchies. The attrition of such sites erodes more than timber and plaster—it strips away the physical record of lives lived with dignity and resistance.

Preservation, of course, is never simple. Stabilization, archival research, and community engagement require not only resources but resolve. Yet the alternative—allowing the structure to vanish—extracts a greater cost. When the last beam yields, what disappears is not just a house but a hole in the narrative of Halesite, of Suffolk County, and of African American history in New York State.

In August 2024, the Town Board resolved upon a course: the dismantling of the house, with key structural elements salvaged, stored, and set aside for a new context. That context has now begun to take form. Plans for Huntington’s first permanent African American museum are advancing. A 1.65-acre harbor-side site was secured in 2023; fundraising is underway; groundbreaking is projected for 2027, contingent upon legislative approval and an estimated $15 million in funding. Central to its design will be the timbers of the Crippen House—an anchor of authenticity, through which the story of a man and a community will continue to speak.

In its next life, the Peter Crippen House will no longer stand exposed to storm, season, and neglect. Instead, its salvaged timbers and architectural fragments will be reassembled within the protective frame of a museum—an environment designed not to weather, but to safeguard. Indoors, the house will be insulated from the very elements that once hastened its collapse, transformed from a structure of vulnerability into one of permanence. In this new context, the house will be secured: no longer at the mercy of wind or rot, it is finally afforded the protection denied to so many sites of African American heritage.

Thus, even as the house disintegrates, it undergoes a transformation. What survives is no longer merely architecture but testimony: material reconstituted into narrative, ruin transfigured into remembrance. The Peter Crippen House may be brought down beam by beam, but its meaning endures—insistent, irreducible, and necessary.

![]()

By Genevieve Barbee, Historic Preservation Intern, Published September 23, 2025