We are pleased to welcome to the blog, Sarah Egan, a graduate curatorial intern, who spent this summer researching objects in Preservation Long Island’s collection, including this intriguing cast-iron birdhouse.

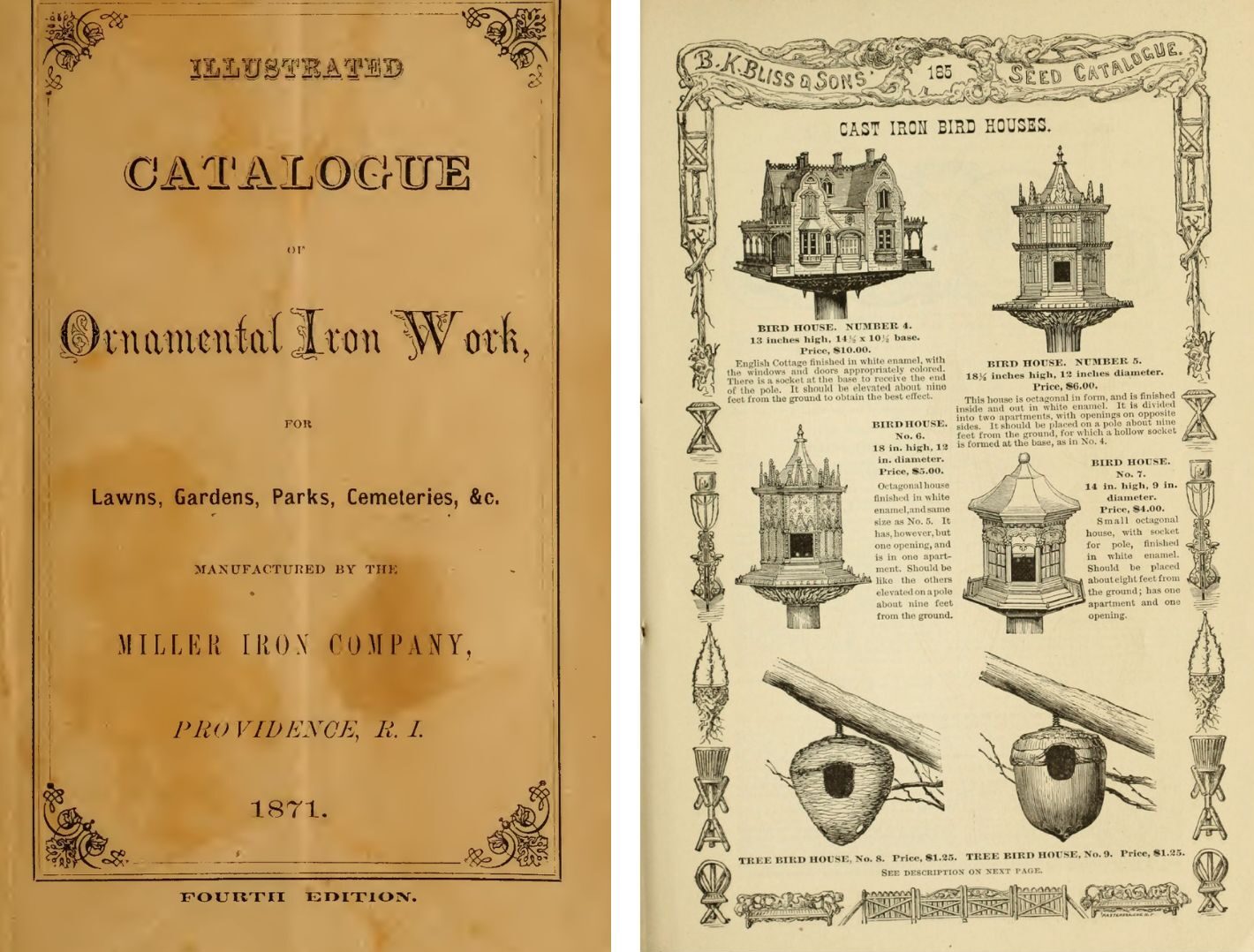

From a picture, or even in-person, Preservation Long Island’s Miller Iron Company birdhouse looks unassuming. Painted grey and white, it could be mistaken for a dollhouse, except that, because it’s made out of solid cast iron, it weighs about twenty pounds. Impressed onto one of the roofs reads: “Miller Iron / Co. Prov, R.I. / Pat,d / Apr. 14, 1868.”

Original advertisements for this object profess its effectiveness and aesthetic qualities; birdhouses that “will furnish a durable and substantial receptacle for the nests of birds, and at the same time afford a pleasing and attractive ornament to the garden or public park.” [1] This particular birdhouse, named in the catalogue as “Bird House. No. 4.” cost $10 in 1871, or about $263.50 today. [2] It was a popular object during its time, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the RISD Museum, and Cooper Hewitt all have an edition in their collections.

This birdhouse holds multiple stories, two of which I will untangle in this blog post: one centered around the house this object was based on, which still stands in Roslyn, and a more thematic story about the rise of bird advocacy, conservation, and landscape architecture in late 19th-century New York, with a special focus on Long Island. In 1916, The Brooklyn Eagle wrote it best: “The little bird house represents a big idea.”[3]

Part 1: The Clifton House

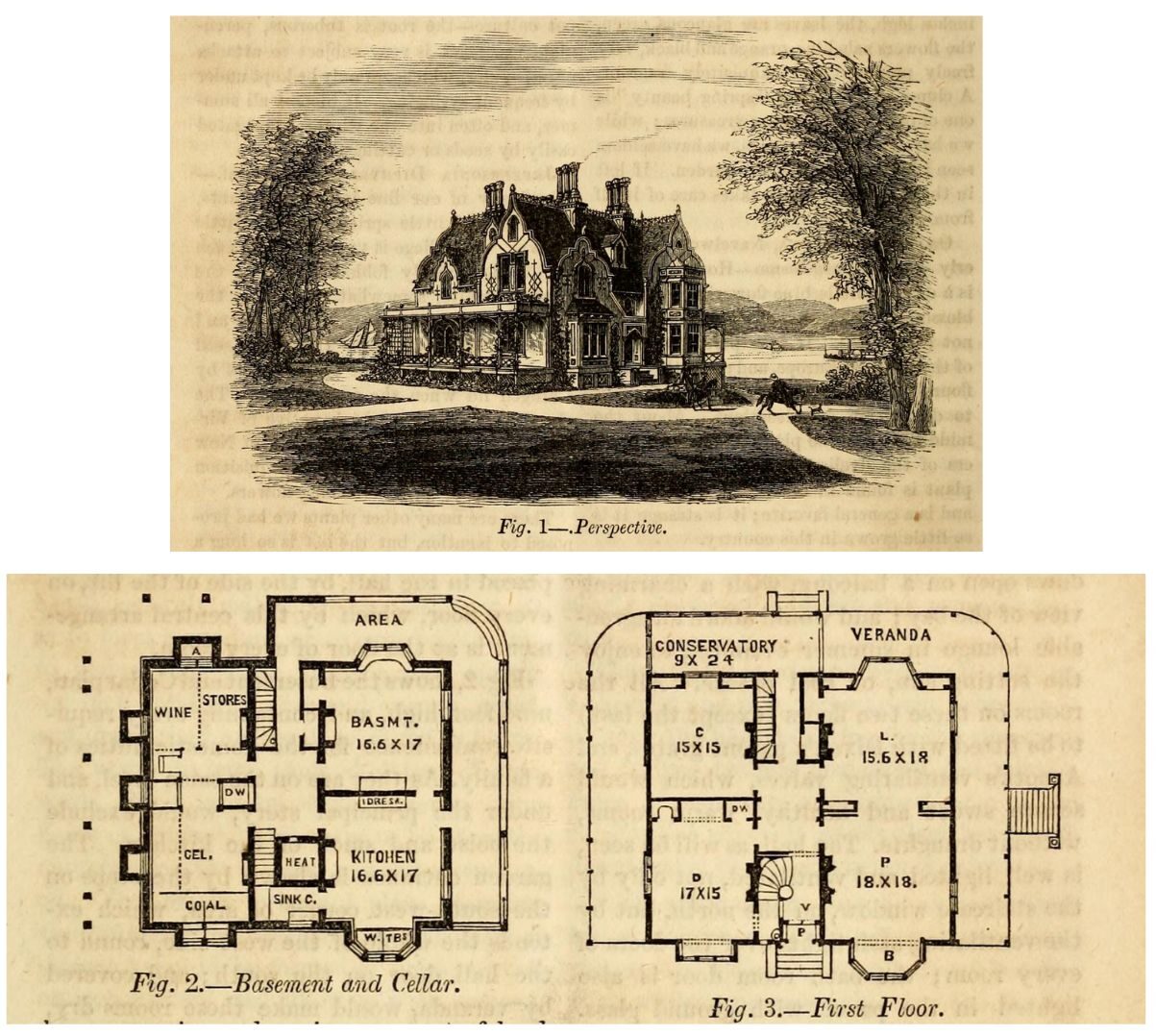

The architectural design of the birdhouse itself is eccentric, with an elaborately pitched roof and Gothic revival detailing. The Miller Iron Company based the designs of this birdhouse on an actual house, “Clifton,” which was built in Roslyn along Hempstead Harbor, in the early 1860s.[4] Frederick S. Copley (1827–1905) designed the house for Mrs. Ann Eliza Cairns (1806–1890), and it was featured in Woodward’s Country Homes (1865) and in The Horticulturist as a “Model Suburban Cottage – in the Old English, or Rural Gothic Style.”[5]

Copley’s summary of the house’s design prioritized ventilation, ease of servant movement, and fire resistance. A tin shoot for sweeping dust into was included on each floor, and a dumbwaiter and hidden stairs were built into the house. He writes that “the house would be nearly fire proof, and life and property secure.”[6] It was a thoughtfully designed residence with a view of the placid harbor and lots of porch space to see it from.

Staten Island-based Copley also designed the Jerusha Dewey Cottage in Roslyn for poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant (1794–1878) in 1862, and likely the Cedarmere Mill for Bryant around the same time, as concluded by the Roslyn Historical Society.[7] While it remains unclear why exactly the Miller Iron Company used his design, Frederick Copley’s creative legacy traveled far in the form of the miniature Clifton birdhouse, affixed on poles in gardens around the Northeast.

Over the years, a variety of notable residents owned or stayed at Clifton. Ann Eliza Cairns’ granddaughter, Blanche Willis (1856–1935), and her husband, Lt. William Helmsley Emory (1846–1917), owned the house from 1876 to 1917. John Demarest (1877–1935) and his wife Nevada L. Ray were the next owners, renaming the home to “Sycamore Lodge.” Demarest played a strong role in the development of Forest Hills Gardens in the early 20th century, and took special interest in the home’s landscape architecture, commissioning the Olmsted Brothers to design his gardens. Famously, General Pershing stayed in the house for a few months in the 1920s, holding military ceremonies and beginning work on his memoirs.[8]

Later owners include radio announcer Glenn Riggs (1907–1975) and his wife Elizabeth A. Laird (1913–1968). A 1988 New York Times article detailed next owners Carol and Millard Prisant’s meticulous restoration of the house, as they tracked down period-accurate furniture and textiles.[9] The couple consulted with landscape designers and planned a Victorian-style garden. To this end, they also acquired a Miller Iron Company Clifton birdhouse.

Considering the Prisant’s careful reconstruction of Clifton’s 19th-century landscape design, historic gardens are fairly ephemeral things. Cast iron birdhouses, on the other hand, sustain the test of time. Surviving landscape plans and newspaper articles provide an understanding of how exactly birdhouses were designed and placed in the 19th century, what they meant to the general public, and, moving into the 20th century, the role these objects played in bird conservation and youth education.

Part 2: Birdhouse Architecture

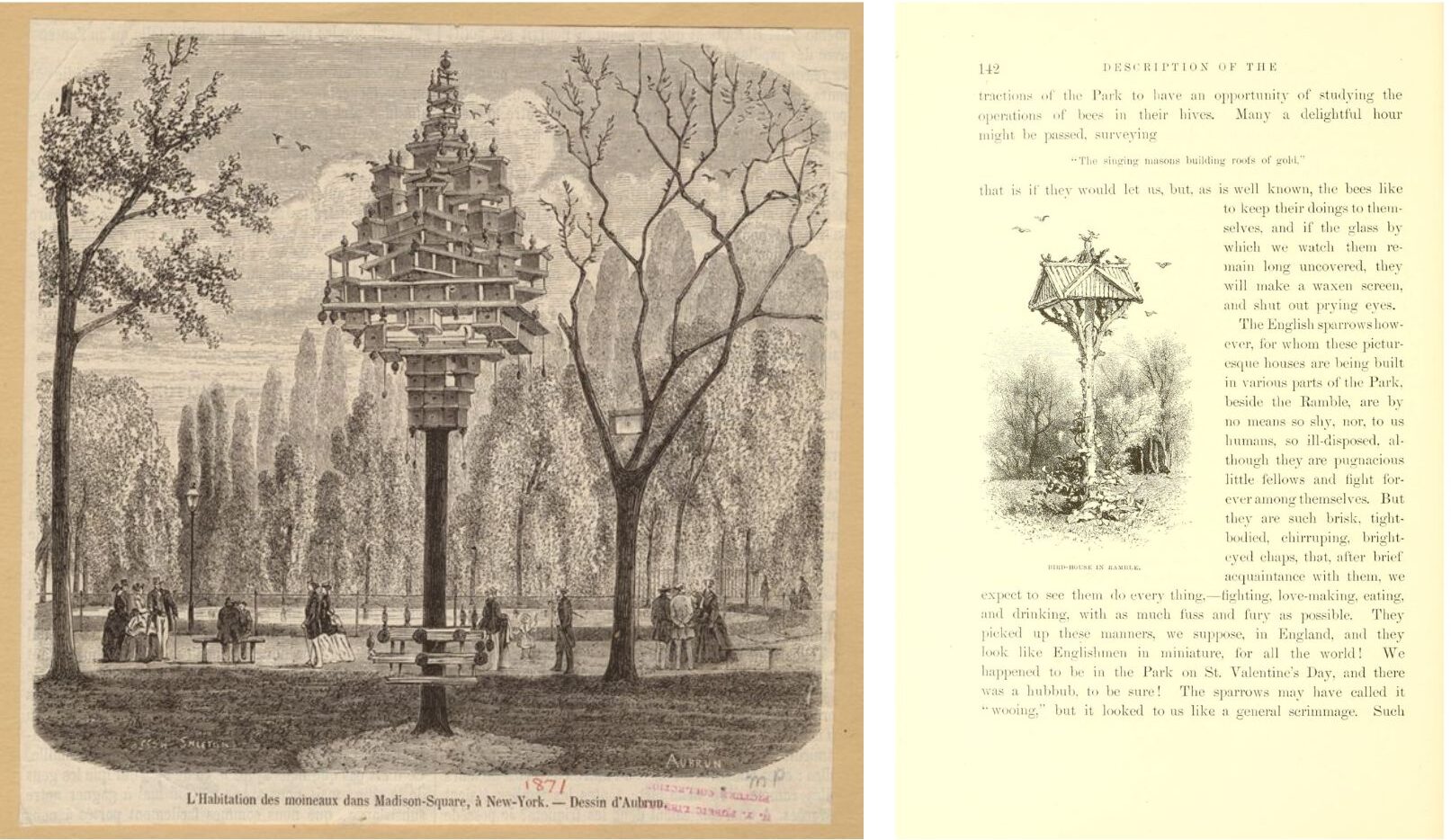

A 19th-century print of Madison Square Garden depicts an elaborate and fantastical birdhouse, and it looks like a more modest one sits in a tree to the right. Clarence Cook’s 1869 A Description of the New York Central Park includes an illustration of a rustic birdhouse in the Ramble, and a cheeky description of English sparrows: “pugnacious little fellows and fight forever among themselves… They picked up these manners, we suppose, in England.”[10] Prospect Park had, at one point, eight-hundred birdhouses.[11] Newspaper advertisements and articles professing the benefits of birds as pest-eaters pop up around the 1860s. In 1871, the city of Brooklyn wrestled on an appropriate budget for birdhouses in the City Hall Park, settling on $50 for thirty birdhouses; as well as a “supply of rice or some other digestible food for the birdies during the Winter months.”[12]

The use of birdhouses was not an entirely new practice in America during the 19th century. Ceramic bird bottles have been excavated at Colonial Williamsburg, including this one made by William Rogers around 1735, reproductions of which are sold in the Colonial Williamsburg store.

Used for attracting birds for insect management, these objects are less architectural in form, but served a similar purpose. The proliferation of public birdhouses in New York parks throughout the 19th century emerged out of an aim for both stewardship and plain entertainment: birds provided songs and visual delight. For more private uses of birdhouses, contemporary paintings provide a visual conception of these structures.

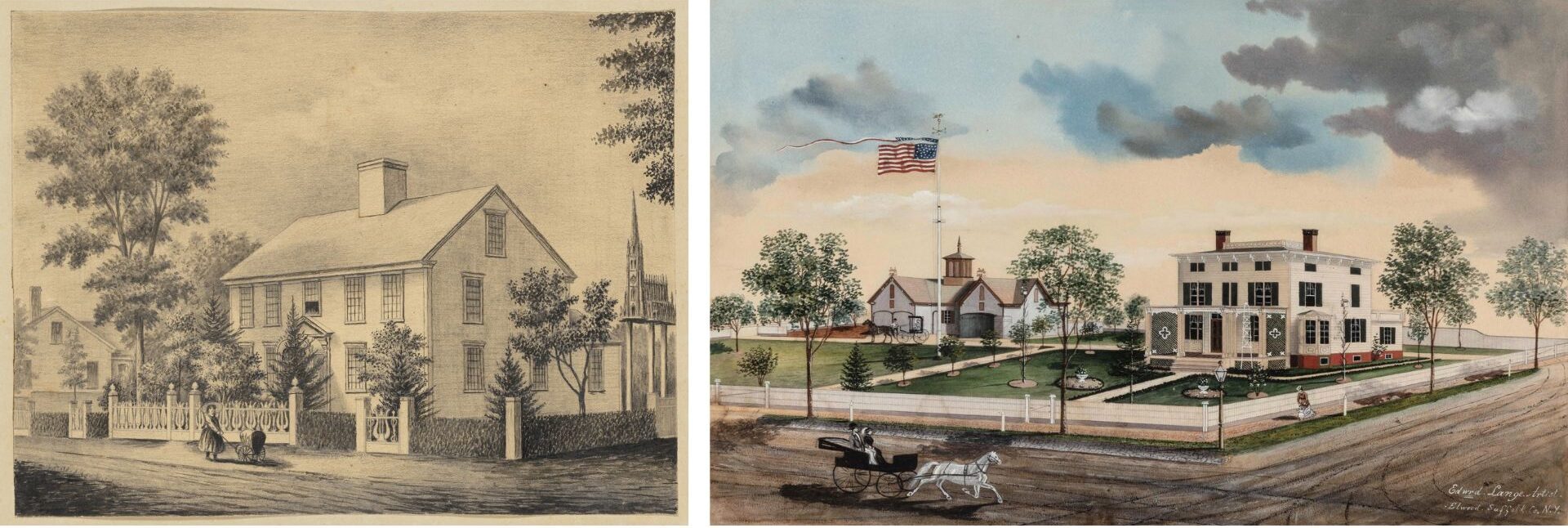

This intriguing illustration of a Federal-style house depicts an elaborate Gothic-style birdhouse (or bird church?) affixed on three tall poles. The Miller Iron Company’s advertisement suggests their birdhouses be mounted nine feet high; it looks like the owners of this house took that contemporary advice a little further.

Birdhouses are depicted throughout the art of Edward Lange, indicating their prevalence on Long Island during this time period. This painting, depicting the Residence of Ruben R. Scudder, Huntington, L.I., includes four birdhouses, two affixed to the roof of the neighboring carriage house.

While the Miller Iron Company produced what we might understand as luxury birdhouses and garden ornamentation, near the beginning of the 20th century, a more crafty movement began. An 1870 article in The Brooklyn Daily Times titled “Wanton Mischief by Boys” describes these crimes:

…It is the little sparrow, whose havoc among the measly worms and other offensive reptiles makes our shaded walks so agreeable in the summer. But these boys, restrained by no such considerations, are actually tearing down from the trees and carrying off the little bird-houses built for the sparrows in various parts of the District.[13]

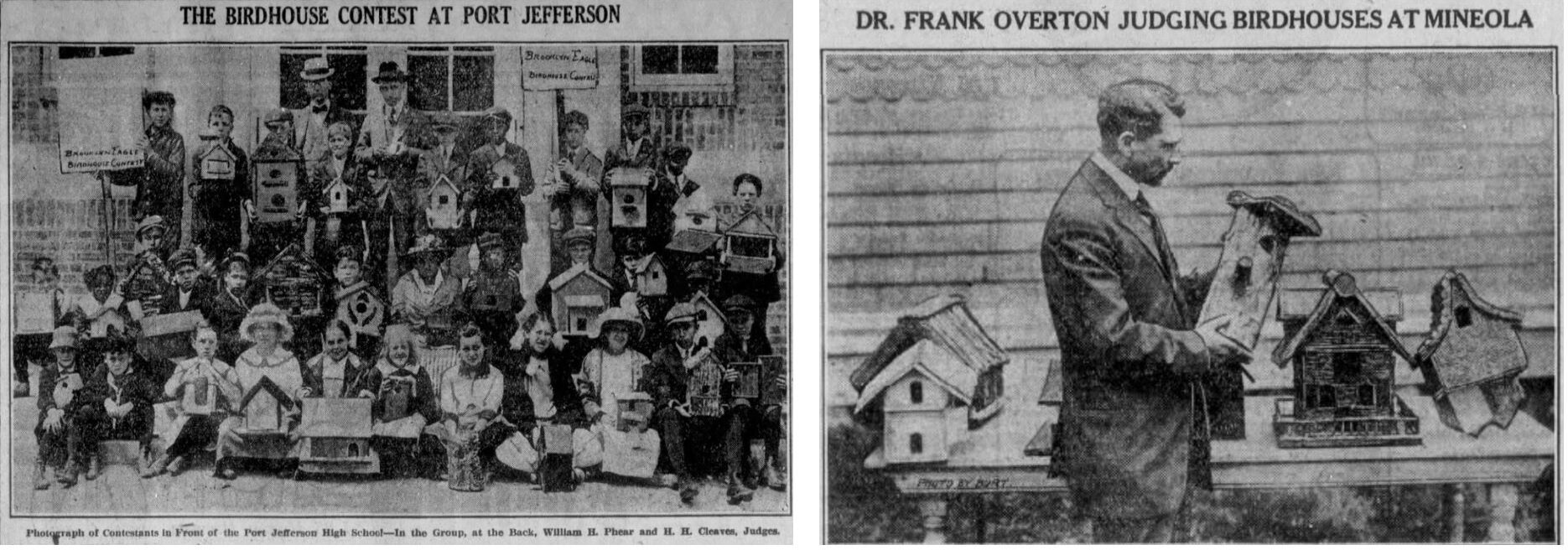

It took some decades, but the movement to educate children to care for the birds—if in the pursuit of their pest-control—took hold in the 1910s. The Brooklyn Eagle held a birdhouse building contest for Long Island’s young boys and girls in 1916, to great, nearly staggering success. In June 1916, a group of sixty children paraded through Port Jefferson with their birdhouses, carrying banners that read “We Love the Birds; They are Our Friends—The Brooklyn Eagle Birdhouse Contest” and “These are for Our Little Feathered Friends.”[14]

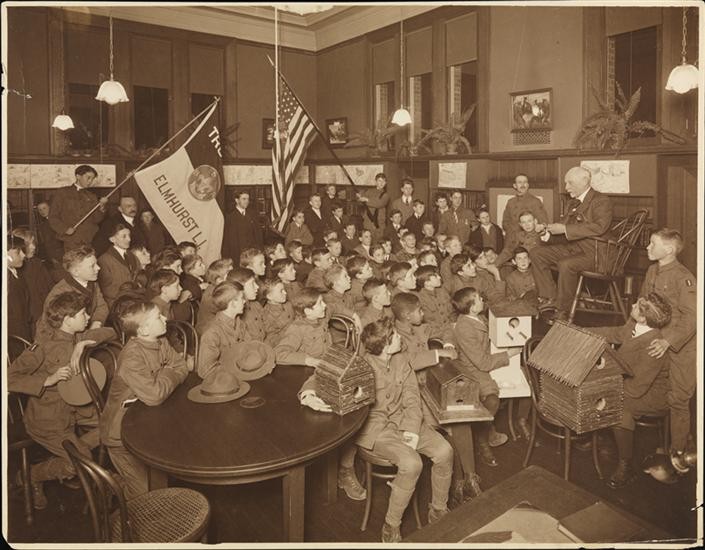

Fourteen-year-old William Fleming of Stony Brook Union School took the first prize medal for his birdhouse made of cherrywood. In the younger age group, Edgar Morely won for his birdhouse version of Lincoln’s log cabin, which used bark to mimic logs.[15] The contest also took hold with the early Boy Scouts of New York, photographed here with their birdhouses and the co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America, Daniel Carter Beard.

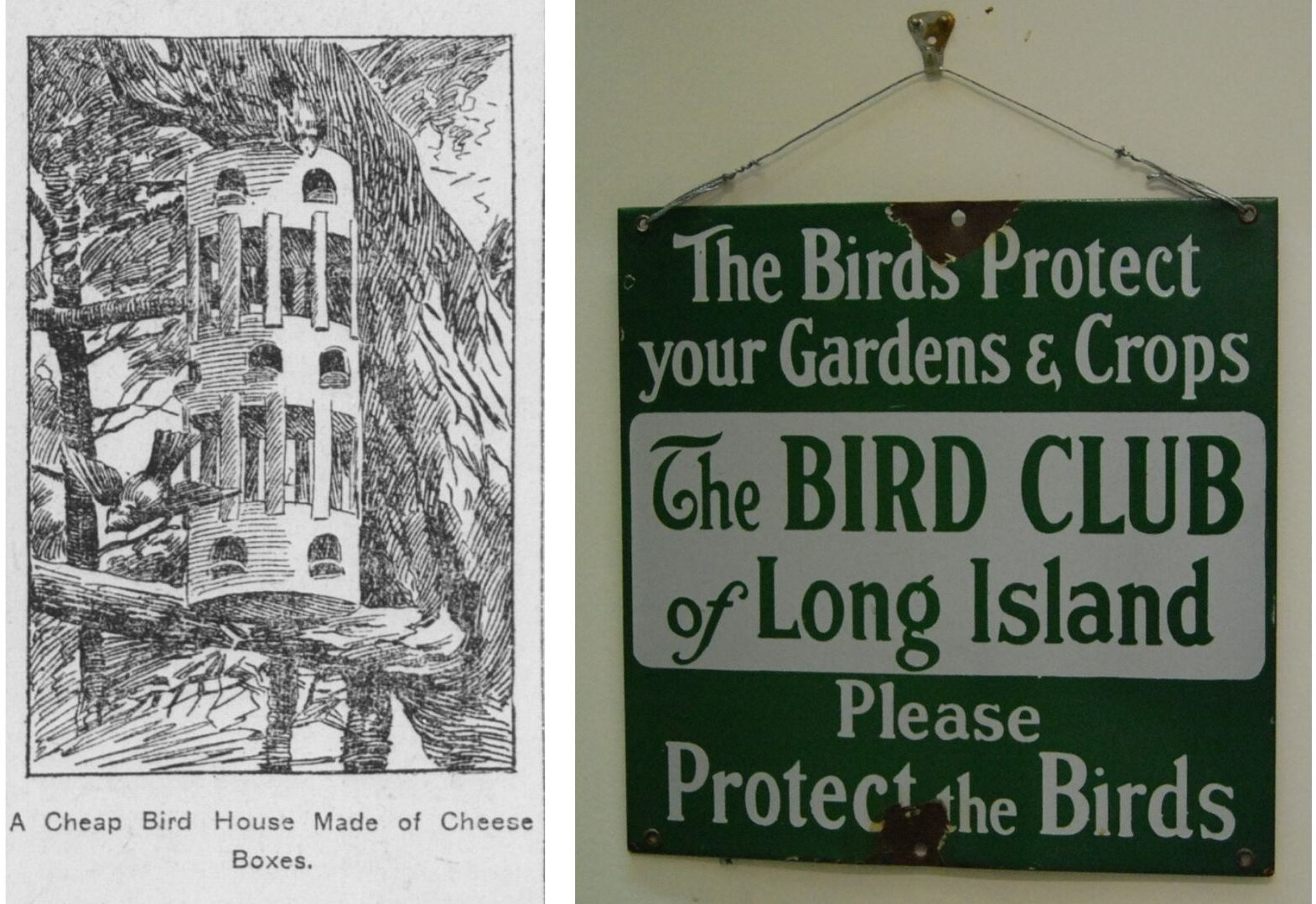

While these home-made birdhouses stray from the austere, sturdy Clifton one, which was conspicuously branded with its company and patent date, they speak to changing attitudes towards bird preservation. Newspaper articles extolled the way building birdhouses introduced Long Island children to handicraft and an appreciation of the natural environment. Many guides for building birdhouses suggested the re-use of materials lying about one’s home, like this illustration, which used cheese boxes.

Not long after the first birdhouse building contest, Theodore Roosevelt established the first National Audubon Society songbird sanctuary in Oyster Bay and the Bird Club of Long Island. Preservation Long Island has an early sign in the collection, and when a bird sanctuary was established near Roosevelt’s grave, the Nassau County Boy Scouts built and put up forty-five birdhouses.[16]

Returning to the Clifton birdhouse, it remains slightly puzzling—there is no entry for a bird to nest. It must have been assumed birds would nest atop the roof or inside the porch, yet the iron must have gotten unbearably hot in the sun.

Sometime in the 70s or 80s, Preservation Long Island’s birdhouse was painted to match the Clifton house in Roslyn, and the other surviving houses have lost their original white varnish. The effect is truly Victorian, in the sense that a black iron birdhouse, with no entryway, could seem haunted. The impracticality of this birdhouse speaks also to the misguided beginnings of nature conservation in the 19th century, where parks were made to be beautiful, and birds provided pleasing songs and pest management for people’s sake. Now kept safely inside the collections of Preservation Long Island, it doesn’t take too much imagination to envision this 19th-century birdhouse perched on a nine-foot tall pole, birds fluttering about it, not totally sure what to make of this thing.

By Sarah Egan, Curatorial Intern

Published August 8, 2025

Sources