Few paintings by Edward Lange match the candid humanity expressed in the artist’s portrait of Charles Jones and his sloop. The artist interrupts the fluid, grey and green, rippling waters of Setauket Harbor with his beautiful rendering of a gaff-rigged oyster sloop. Lange’s attention to detail is remarkable, from the accurately painted rigging lines to the detail of the clam rake sitting on the deck. Perhaps most evocative is Jones himself. He leans casually against his sloop’s boom, smoking his pipe, looking directly at us. It’s hard not to recognize and meet his gaze.

Rarely does Lange offer us an opportunity to stand face-to-face with the people he painted. His typical views encourage us to look through a window of his own design, into the world as he saw it. Our eyes peer at manicured estate gardens, across fields of hay, and into clusters of farmhouses surrounded by outbuildings. For the most part, we are on the outside looking in. The people that populate these landscapes (if they’re included at all) are accessories to the scene, providing a sense of scale. Lange’s painting of Jones is a welcome exception. He’s on equal footing with us in this picture, watching us just as we watch him. It seems only appropriate that this standout picture happens to share with us the experience of a bayman, one of the most prolific and iconic professions of nineteenth-century Long Island.

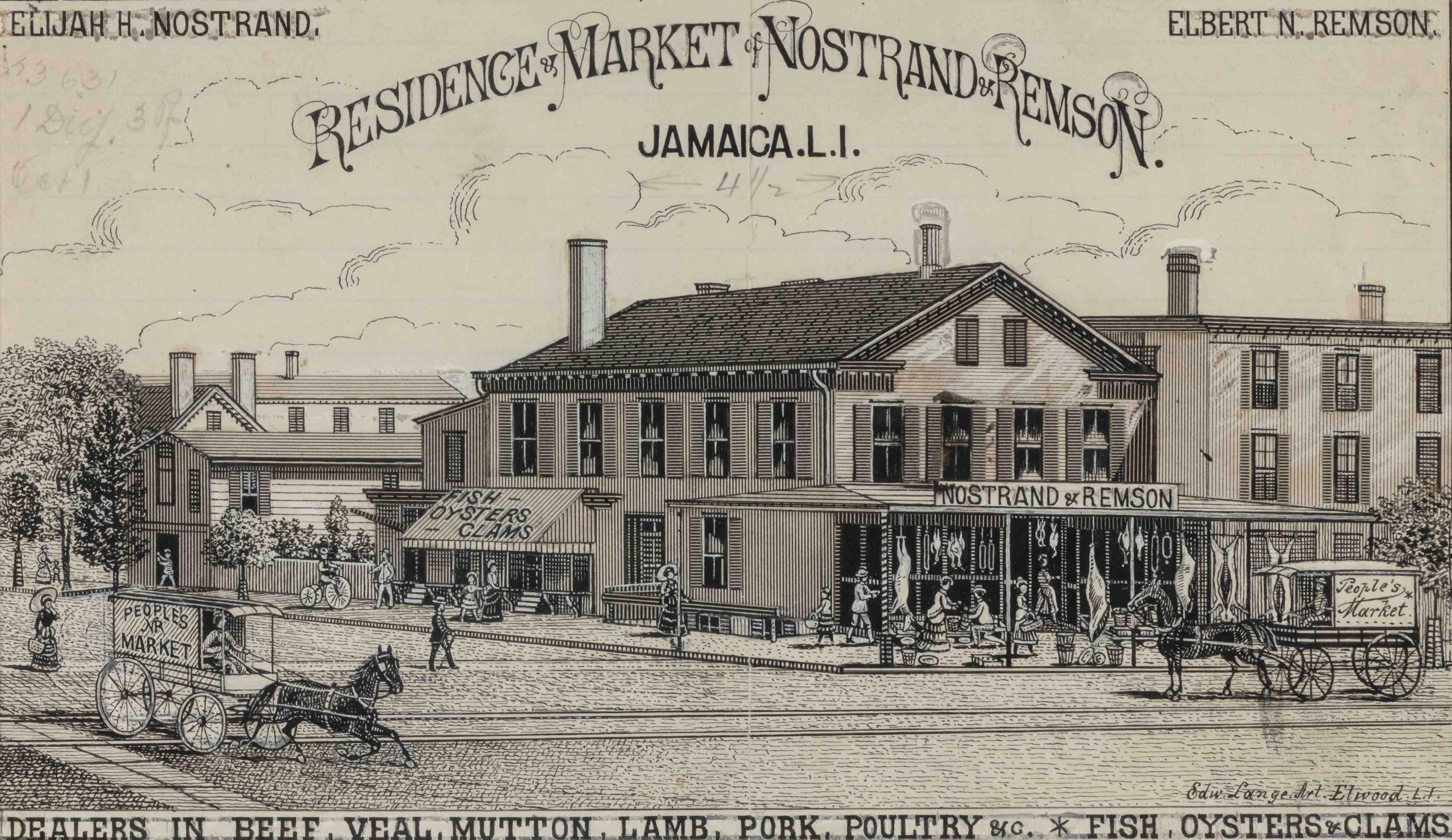

In the 1880s, when Jones was working out in Setauket Harbor, Long Island’s baymen brought thousands of bushels of shellfish annually to New York City’s markets. Domestically and internationally, oysters were known as the quintessential delicacy of the city. Baymen delivered their wares to the docks, where street-side vendors and grocers quickly moved the shellfish along to storefronts and then into the hands of consumers. Lange’s advertisement for Elijah Nostrand’s and Elbert Remson’s market in Jamaica, Queens highlights the consumer end of this supply chain. The harvest and sale of New York oysters were a part of a macroeconomy that involved thousands of similar storefronts and an equal number of baymen supplying them with fresh product. Jones spent his life working the coastline of the North Shore, deeply invested in the business of New York’s aquaculture. His descendants even maintained that Jones compensated Lange for the watercolor with none other than a bushel of oysters.

Preservation Long Island recently welcomed Charles Jones’ Sloop back from conservation thanks to generous support provided through the NYSCA/GHHN Conservation Treatment Grant Program, administered by Greater Hudson Heritage Network. Nearly a full year ago, curator Lauren Brincat and curatorial fellow Peter Fedoryk conducted a thorough examination of the twenty-six Lange artworks in Preservation Long Island’s collection and found Charles Jones’ Sloop in need of attention. Over the one hundred and forty years since Lange painted it, the surface accumulated oily residue from fingerprints, flyspecks, and patches of dried mold. After consulting conservator Andrea Pitsch, of Pitsch Conservation, it was decided that the artwork would greatly benefit from a thorough surface cleaning and selective inpainting in areas of loss.

Andrea used a scalpel to mechanically remove these distractions from the surface of the painting. She also worked to stabilize flaking paint around areas where the paper had creased and caused pigment loss. This kind of conservation is both restorative and preventative. Inpainting areas of loss maintains the integrity of the original image, while stabilizing it against more problematic damage in the future. Finally, on the back of the artwork, Andrea reinforced splitting areas along the edges of the paper with strips of mulberry paper secured with a wheat starch paste. The strengthening of these areas of weakness will also help mitigate further degradation. The final step involved reframing the conserved artwork back into its frame. This piece is fortunate enough to still be paired with its original frame, made from oak.

Mike Hambrook, of Oyster Bay Frame Shop, was responsible for fitting the artwork back into its frame. He took care to line the interior rabbet of the frame with metallic tape to create a buffering layer between the wood of the frame and the edge of the watercolor, to prevent any further damage to the artwork’s paper. Thanks to Andrea and Mike’s diligent work, Charles Jones’ Sloop will continue sharing the rich history of Long Island’s oysters and baymen with generations of Long Islanders to come.

You can learn more about Charles Jones’ Sloop and other paintings by Edward Lange by visiting The Art of Edward Lange Project website and exploring A World in Motion, a digital exhibition curated by Peter Fedoryk that reflects on how Lange’s artwork is overflowing with activity and excitement.

The NYSCA/GHHN Conservation Treatment Grant Program, administered by Greater Hudson Heritage Network, is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. Additional support is provided from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation.

By Peter Fedoryk, Curatorial Fellow

Published July 21, 2022