This post is part of a blog series connected to Preservation Long Island’s Jupiter Hammon Project, a multi-year initiative launched in 2020 to reevaluate how Preservation Long Island engages visitors at Joseph Lloyd Manor (completed 1767) with the site’s history of enslavement and the story of Jupiter Hammon, one of the earliest published African American writers.

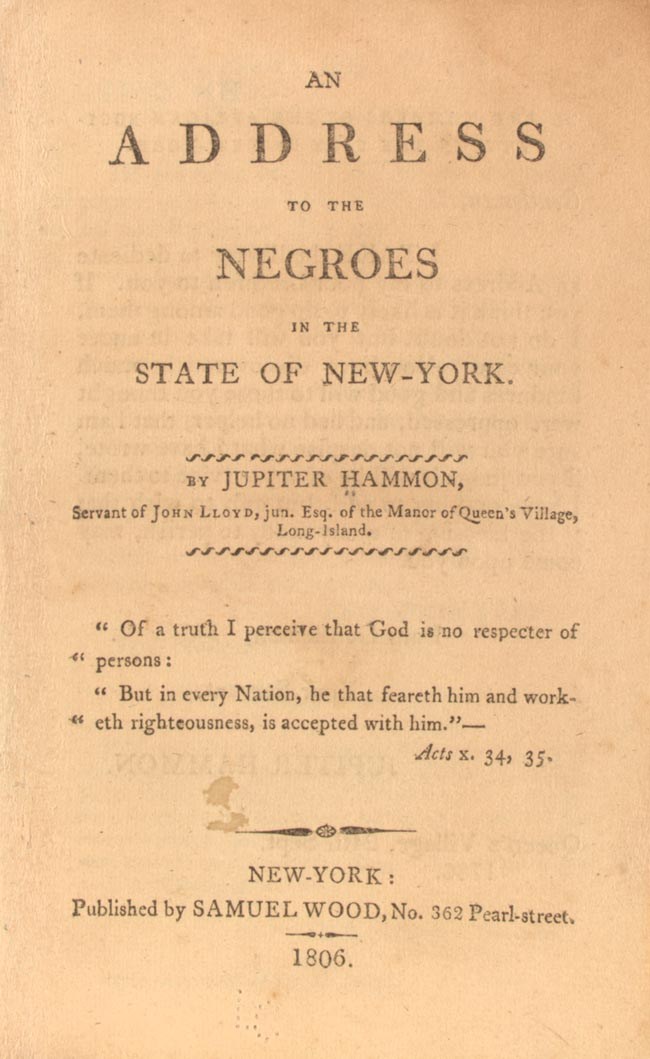

In 1786, Jupiter Hammon penned “An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York” for the African Society, the first Black organization in New York City. Written at Joseph Lloyd Manor, where he lived in bondage to the Lloyd family, Hammon’s work grapples with the prospect of freedom for members of New York’s enslaved community. Hammon conveys joy and sadness, expressing hope for the young and empathy for his fellow elders, who, like himself, spent their entire lives in bondage: “Though for my own part I do not wish to be free, yet I should be glad if others, especially the young negroes were to be free, for many of us, who are grown up slaves…should hardly know how to take care of ourselves…”

Hammon was 75 years old when he wrote those words and aware of what emancipation would look like for elderly enslaved people indifferently manumitted by their enslavers. Once freed, these men and women were left homeless and destitute. Unable to labor as they once had, they struggled to support themselves, and since enslaved families were almost always torn apart, few had relatives nearby to care for them.

Two years after Jupiter authored his address, New York passed the 1788 “Act Concerning Slaves.” It outlawed the sale of enslaved men, women, and children imported from outside New York. However, buying and selling enslaved persons within the state remained legal. The act further guaranteed that enslaved individuals, and the children of enslaved mothers, would remain in bondage for life unless emancipated by their enslavers. In an effort to address the poverty that freed men and women inevitably faced, the law required enslavers to provide financially for any person they manumitted over the age of 50 by supplying bonds valued at no less than 200 pounds to the local Overseers of the Poor.

Jupiter Hammon was 88 years old when New York passed its first gradual emancipation law in March of 1799. Whereas the 1788 act eliminated the importation of enslaved individuals into New York, this new law prevented future children from being born into slavery for life. New York was the second-to-last state in the North to pass any type of emancipation law, reflecting how deeply invested New York was in the business of slavery. Called “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” it ruled that any child born to an enslaved mother after July 4, 1799 was considered free. To ensure that enslavers continued to reap the benefits of a child’s most productive years, boys born to enslaved mothers remained bound as servants to their mothers’ enslavers until they were 28 and girls until they were 25.

Four generations of the Lloyd family enslaved Jupiter Hammon. Although the 1799 gradual emancipation law did not apply to him, and despite Hammon’s reservations about his own freedom, he was probably manumitted around 1793 following the death of John Lloyd II (1745–1792), who had inherited the Manor and its enslaved workforce from his uncle, Joseph Lloyd (1716–1780). Hammon’s whereabouts after manumission provide further insight into the complicated experience of gradual emancipation in New York. A man named “Jupiter” appears in the 1800 Huntington Town census listed as the head of a household of three. Research by Charla Bolton and Rex Metcalf support that this man was Jupiter Hammon and that the household also comprised Benjamin Hammon (ca. 1761–1827), Jupiter’s grandnephew, and Phoebe (1767–after 1830), Benjamin’s wife.

Benjamin was born into slavery but, according to a statement he gave to the Overseers of the Poor of the Town of Huntington, was freed by John Lloyd’s widow, Amelia Lloyd (1760–1818), upon his death. Amelia may have freed Jupiter as well, although census records indicate she continued to enslave people into the nineteenth century. By 1799, Hammon was probably living in a house Benjamin purchased in Huntington Village and likely supported the family with income from an orchard planted for Jupiter before the Revolutionary War. After Jupiter died around 1806 (he was in his 90s), Benjamin did not inherit the orchard and was forced to sell the house. In 1821, he appealed to the Overseers of the Poor for relief. The hardships Benjamin faced show that emancipation brought challenges for young and old alike. Low wages and scarce work made it difficult for freed men and women to hold on to land or wealth. The consequences of these historical disparities continue to impact American society today. In 2019, poverty rates were twice as high for Black New Yorkers.

Jupiter Hammon did not live to see the passage of New York’s second and final gradual emancipation law in 1817, which established a legal path to freedom for all enslaved New Yorkers. The law stipulated that any enslaved person born before July 4, 1799 would be freed on July 4, 1827 and that the children of enslaved mothers born after the passage of the law on March 31, 1817 would remain bound until the age of 21. These complicated provisions are a source of confusion about the abolition of slavery in New York. Although this new law legally ended slavery in New York on July 4, 1827, it did not in practice. Children remained bound to their mothers’ enslavers into the 1840s.

Chattel slavery in New York has a long history, beginning in the 1620s and lasting into the 1840s. Abetted by dehumanizing racist ideologies that viewed enslaved people as property, slavery generated enormous wealth for New Yorkers who benefited from it. Rather than ending slavery outright, New York enacted a series of laws that created slow and often complicated paths towards freedom. The works of Jupiter Hammon, along with the experiences of his family members after manumission, offer insight into the paradoxical impacts of gradual emancipation in New York that were both compassionate and cruel.

By Lauren Brincat, Curator, Preservation Long Island

Explore the people and places of Jupiter Hammon’s world with our interactive story map:

Sources and Further Reading

Benton, Ned. “Dating the Start and End of Slavery in New York.” New York Slavery Records Index. https://nyslavery.commons.gc.cuny.edu/dating-the-start-and-end-of-slavery-in-new-york/ (accessed April 20, 2020).

May, Cedrick ed. The Collected Works of Jupiter Hammon: Poems and Essays. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2017.