This Black History Month, Preservation Long Island is looking back at five years of the Jupiter Hammon Project and planning for the future.

By Andrew Tharler, Education and Engagement Director

In 2019, Preservation Long Island conducted an internal evaluation of Joseph Lloyd Manor’s strengths, limitations, and opportunities for growth. The challenges were glaring. The historic house had little room for parking, there was no way for visitors to book tours online, and the signage had faded over the years. Listed among these more dire pronouncements was a vital panacea: the story of Jupiter Hammon, America’s first published Black poet. Hammon spent nearly his entire life enslaved by the Lloyd family and authored his most significant works while in bondage at Joseph Lloyd Manor. Despite his towering significance, Hammon had received cursory attention at the house; the tour script mentioned him only in the intro and outro. These public tours differed sharply from Preservation Long Island’s school programs, which were among the first on Long Island to focus explicitly on the history of slavery. The resources prepared by Preservation Long Island’s Educators in the 1990s were heralded in the media and sought by teachers even beyond New York.

The Jupiter Hammon Project marked an opportunity to reinvigorate Joseph Lloyd Manor by expanding the history presented to the public. The project was radical in its conception: the historical focus would be driven by communities rather than curators, process would be valued as much as results, and an 18th-century Georgian manor house would become a place for meaningful conversations about Black and Indigenous history. By the Spring of 2019, Preservation Long Island had assembled an Advisory Council of Long Islanders with ties to diverse communities in the region. To prepare for the hard work of confronting the history of slavery, the staff and Advisory Council underwent Arc of Dialogue training led by The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.

In keeping with this dialogic spirit, the project launched in 2020 with a series of conversations. PLI empaneled scholars and museum professionals to participate in public roundtables exploring the life and work of Jupiter Hammon. Originally planned as in-person programs, these panels were forced online by the Covid-19 pandemic. The shift to Zoom was disappointing but fortuitous. 534 people watched as Professors Jennifer Anderson, Nicole Maskiell, and Craig Wilder discussed Long Island’s position within the Atlantic slave trade, a far larger audience than Joseph Lloyd Manor could have accommodated in person. Audience interest was sustained over the subsequent panel discussions. The next roundtable convened Phillip M. Richards, Jesse Erickson, and Malik Work to situate Jupiter Hammon’s writing within 18th century literature and religious thought. In the final panel, Dina Bailey, Jessa Krick, and Joseph McGill explored strategies for confronting the topic of slavery at historic sites.

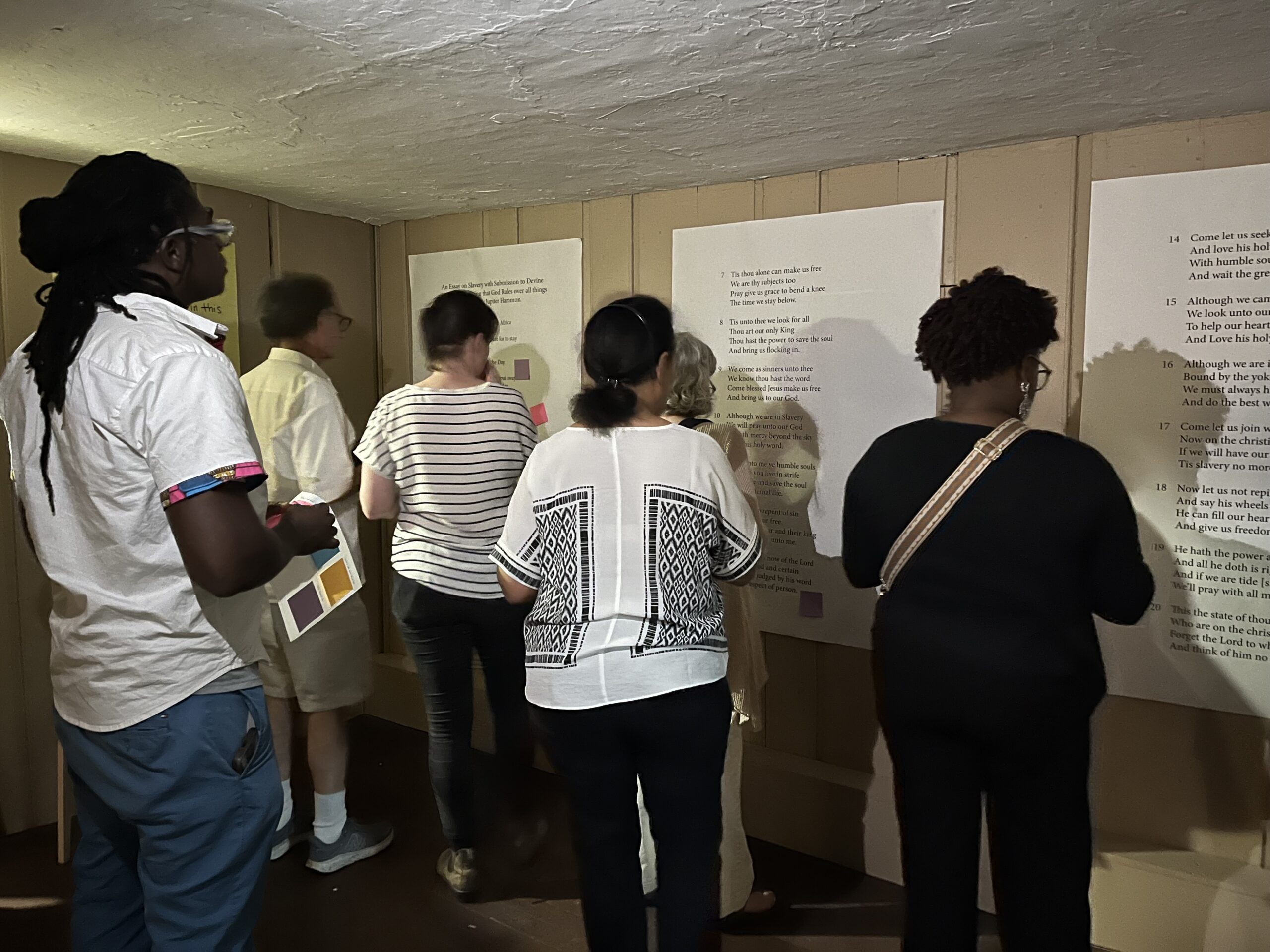

The themes and feedback that emerged from those roundtables have guided the project ever since. In her final report, consultant Christina Fewerda identified several areas of audience interest. Calls to meld history with contemporary art were later answered with new programs inviting poets Malik Work and David Mills to rhapsodize in the garden of Joseph Lloyd Manor. Visitors on public tours now listen to Work’s rendition of Hammon’s final poem “An Essay on Slavery” and grapple with themes of faith and freedom. Roundtable audiences sought enhanced K-12 teaching and learning at Joseph Lloyd Manor. Now all students arriving on school programs engage critically with Jupiter Hammon’s writing and use primary sources to discover the stories of other people enslaved at the site. Audiences suggested creative collaborations to enrich historical inquiry. Since then PLI has collaborated with Lloyd Harbor Historical Society, Humanities New York, and the Caribbean American Poetry Association on public programs bringing different historic sites into conversation and drawing connections between the past and the present. David Waldstreischer delivered a lecture on Jupiter Hammon’s ties to Phillis Wheatley, and the Advisory Council worked with Jennifer Anderson and Chief Curator Lauren Brincat on a panel exhibition detailing Hammon’s multigenerational entanglement with the Lloyd family.

Aside from this pop-up exhibition, Joseph Lloyd Manor has remained largely unchanged during the Jupiter Hammon Project. Mahogany furniture still presides over the parlor, and baskets of uncanny fake food animate the colonial kitchen. But these period rooms have become arenas for new conversations. Tours call attention to how the house’s 1767 floor plan encoded inequalities in its layout while also affording moments of respite in its liminal spaces. Pathways through the house have also changed. As visitors sit in the enslaved quarters and descend the back staircase once reserved for the enslaved community, they reflect on architecture’s capacity to promote or deny movement, facilitate or hinder communication, and shape the way we experience the world.

There have also been calls for more substantial physical alterations to Joseph Lloyd Manor. Separate workshops led by Dialogic Consulting and BlackSpace offered PLI staff, the Advisory Council, and community stakeholders new tools to reimagine what a historic house could be. PLI converted these ideas into physical installations intended to spark conversations abound the power of place, the stories told by artifacts, and poetry as an act of courage. These interventions were considered prototypes, as their permanent status depended on the feedback we received from stakeholders. To that end, last year we invited the public to preview the new experience and share feedback in focus groups. The response was enthusiastic, and the constructive comments we received will shape the next iteration of these prototypes.

This year, PLI will continue to test new ideas at Joseph Lloyd Manor and, most critically, seek new audiences. Although encouraging in their feedback, participants in the first series of focus groups did not fully reflect the diversity of the local Huntington community we were hoping to attract. Curiously, the final report prepared after the roundtables also noted that “Despite the care and persistent effort to connect, participation from members of the local Black and descendant community was relatively low.” To cultivate new participants and ensure continued stakeholder investment, the next year of the Jupiter Hammon Project will be devoted to relationship-building and outreach. PLI will engage directly with Black organizations in and around Huntington through presentations, participation in community events, and a new series of focus groups empowering audiences to help shape the future of the site. Building trust will take more time, listening, and self-reflection. But any permanent changes to Joseph Lloyd Manor must await the input of our stakeholders. There are certainly drawbacks to this grassroots approach. Progress can slow, decisions demand consensus, and circumstances may draw people away from the project. As stewards of the historic house, PLI could simply create new installations on its own. But proceeding in this way would be antithetical to tenets of dialogue and community engagement at the heart of the Jupiter Hammon Project.

Even if there is more work to do, it is worth reflecting on what the Jupiter Hammon Project has already accomplished. Tours, public programs, and school field trips have brought the poetry of Jupiter Hammon to larger audiences than ever before. We have presented at libraries, professional conferences, cultural organizations, and literary societies. The project has been covered by podcasts, radio shows, PBS, CBS, and Newsday. Joseph Lloyd Manor was honored as a National Literary Landmark. We have pursued stories of enslaved people in archives, cemeteries, attics, and the other solitary places where hidden histories dwell. After all this, some may wonder why Joseph Lloyd Manor isn’t already replete with touchscreens, soundscapes, and all the exciting things that attract modern museum-goers. Admittedly, I sometimes share in this frustration. Jupiter Hammon cautioned against impatience in his own time: “Now let us not repine / And say his wheels are slow / He can fill our hearts with things divine / And give us freedom too.” Hammon’s metaphor is apt. A wheel turning slowly is still making a revolution.