Preservation Long Island is pleased to welcome guest blogger Will Mack, an ACLS graduate fellow and PhD candidate in history at Stony Brook University. As part of his internship with Preservation Long Island, Will explored the larger history behind this 20th-century watercolor view of a home once located in the vibrant African American and Indigenous Valley Road Community in present-day Manhasset.

Following the enactment of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, German immigrant artist and landscape painter Ernest Cramer (1877–1953) was hired by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to create artworks for the Federal Art Project. His watercolor “Old Indian Homestead (Clinton Smith Cottage)” was likely painted sometime between 1935 and 1942. The view looks down Valley Road, now Community Drive in Manhasset. Although the painting focuses on a single structure, the home of David Clinton Smith, the early nineteenth-century dwelling was one of approximately 30 structures that once stood in Success, a community of enslaved and free Black and Indigenous people that dates back to eighteenth century.

Valley Road was the main thoroughfare in Success, an area that remains part of the traditional homeland of the Matinecock Tribal Nation. Despite European colonists dispossessing Matinecocks of much of their lands, they did not leave the area. Both free and enslaved Indigenous and African-descended peoples lived along the thoroughfare, intermarrying and developing their own community. Initially called the Valley Road Community, the area has been referred to by various names over time, including Success, Lake Success, and Lakeville. The name Success is believed to derive from Sacut, a Matinecock word meaning “at or near the outlet of a pond.” [1] Today, the area is part of the hamlet of Manhasset.

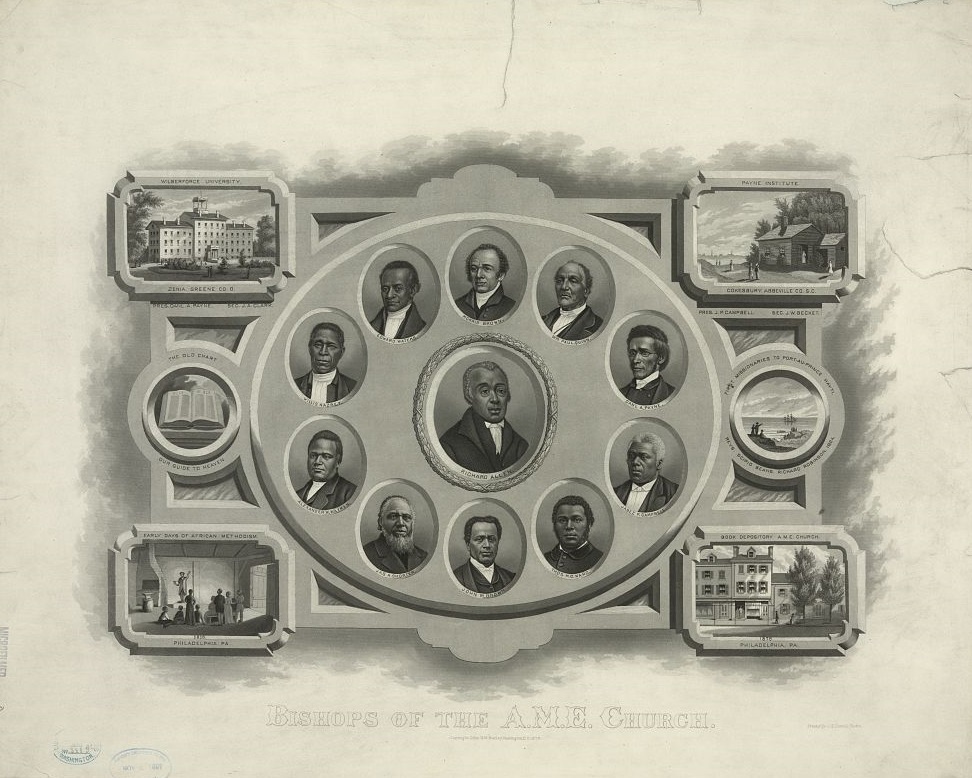

During the late 1700s to early 1800s, Valley Road was not the only interracial community in the New York City region. Not too far away in Flushing, Queens, free Black, Indigenous, and white people formed the African Methodist Society in 1811. It would eventually coalesce as the Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church following the expansion of the denomination in 1819. The origins of the AME Church can be traced to the late eighteenth century when Black members in Philadelphia, led by formerly enslaved preacher Richard Allen, withdrew from the Methodist Episcopal Church due to racial discrimination. [2] The Macedonia AME Church in Flushing would become central to the local Black and Indigenous community. A decade after its founding, Black religious leaders Moses and Susannah Coss moved from Queens to the Valley Road area and established a congregation in 1821. The group originally met at the home of Moses Coss. Like the AME churches, it quickly became a safe haven for enslaved, free Black, and Indigenous worshippers. [3]

Following New York’s passage of a series of gradual emancipation laws beginning in 1799, slavery legally ended in the state in 1827. The Valley Road Community subsequently attracted freed people from the surrounding areas seeking land and homes of their own. Under the leadership of Mohawk George B. Smith, the community grew and the town of Lakeville was founded. Here, Indigenous peoples and the formerly enslaved shared cultures and traditions, from clamming on Lake Success to celebrating an Autumn festival every September. [4]

Valley Road continued to thrive, and in 1831, the congregation was able to purchase land from Reverend George Treadwell on which they built a church two years later. Originally called the “Colored Peoples Meeting House,” its name eventually changed to Lakeville AME Zion Church in recognition of its roots in the Queens AME church and it legacies of Black freedom and inclusivity. [5] The original wooden-frame church is still in use and is one of the oldest Black churches on Long Island. [6] The building, along with a graveyard containing the remains of Civil War and the Spanish-American War veterans, are the only features from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries that remain today. Unfortunately, the Clinton Smith House no longer survives, making Cramer’s watercolor an important document.

As the United States recovered from five years of civil war and struggled to create a truly interracial democratic republic, the church became central to Black communities across the country. It was through the church that families united, politics were discussed, and leaders emerged. Next to the church in Success, approximately 30 families came together in 1867 to help build “The Colored Children, Institution, U.S.A.,” the first free Black school in Nassau County. Evidently, the school was a success. According to the 1910 census, 99% of respondents in the community could read or write. [7] When the children were finally allowed to enter the area’s public schools in 1919, the school closed its doors and was subsequently torn down. [8]

In the aftermath World War II, intense development and suburban sprawl on Long Island negatively impacted the region’s historic communities of color. In Success, racist redlining practices excluded many Black people from purchasing new homes in the area or forced them to move to segregated Black communities in other parts of Long Island. Nevertheless, Black businesses continued to thrive in the adjacent neighborhood of Spinney Hill into the 1980s. During the World War II era, the residence of David Clinton Smith was one of a few houses still standing. Born in Success in 1863, Smith likely attended Institution U.S.A., where he learned to read and write. He became a farm laborer and later found employment as a caretaker on a local estate. Smith married Fannie Jane Waters, a woman of Unkechaug, Montaukett, and Shinnecock descent. The couple had thee daughters, Maud, Eva, and Julia, and a son, James. Multiple generations of Smiths, Treadwells, and Crawfords would reside in the home together. [9]

By the late twentieth century, a Smith descendant was still living on what was once called Valley Road. In 1975, David Smith’s niece, Grace Amelia Smith, resided in a house near the spot where his once stood. At eighty-one years old, Grace lived alone in the ancient structure without heat or indoor plumbing. Although her home was in need of extensive repairs, Miss Smith remembered with fondness the community that used to be Success. She recalled the annual Autumn festivals and reminisced about her long-gone family and neighbors. “We were happier then,” she remembered. “We worked hard and everyone was a neighbor. If one family had trouble, a neighbor would come to the door to help . . . We lived for each other then. Our lives were built around family.” [10]

Today, the Lakeville AME Zion church is recognized as a historic landmark, and in 1977, the Community Drive corridor was designated the Valley Road Historic District. Unfortunately, neither the Clinton Smith House nor Grace Amelia Smith’s home still stand. Nevertheless, the history and meaning of Success continue to resonate. As one community member noted when she moved to the area and learned about the church and its deep historic roots, “there was something spiritual about the place, the people, the location. You look around on this history; it [takes] you back into time.” [11] Although few physical markers of Success’s past survive, what is left are powerful reminders of Long Island’s vibrant African American and Indigenous history and culture.

By Will Mack, ACLS Fellow and PhD Candidate in History, Stony Brook University

Edited by Lauren Brincat, Curator

Published April 28, 2022

Endnotes