Preservation Long Island’s curatorial intern closely examines its important collection of early nineteenth-century woven coverlets.

My name is Emily Werner and I’m taking over the blog today to share a little bit about my experience as a collections and curatorial intern at Preservation Long Island! I have recently finished my coursework for my M.A. in Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, & Museum Practice at the Fashion Institute of Technology. I am putting my knowledge of textile analysis and collections care to use by researching and cataloging Preservation Long Island’s extensive collection of early nineteenth-century woven coverlets.

These woven bed coverings were some of the most richly patterned and highly prized textiles in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American homes. While some homes were equipped with two- and four-shaft looms capable of producing simple domestic textiles like sheets, blankets, or towels, complex coverlets were often the product of professional weavers. In the early nineteenth century, many professional weavers immigrated from Germany, Scotland, Ireland, or England after lengthy apprenticeships in specialized fields, such as damask or carpet weaving. These “fancy weavers” settled in small towns along the east coast, including New York, and adapted their knowledge of specialized techniques for weaving double-cloth carpets to weaving “bed carpets” or “carpet coverlets.” Professional weavers were almost exclusively men, though some women wove textiles at home for domestic use, especially in more rural areas.

Professional weavers made coverlets for specific customers, typically women, sometimes weaving her name and the date into the corner blocks or along the border. The practice of naming and dating coverlets in this manner is thought to have originated on Long Island. The earliest named and dated Long Island coverlet was made in 1810 for Ann Carll by the Mott Mill in Westbury (now in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum). The customer or a female relative of the woman for whom the coverlet was made often spun the wool, which the weaver combined with factory-spun cotton. Early coverlets could also be made with wool and linen.

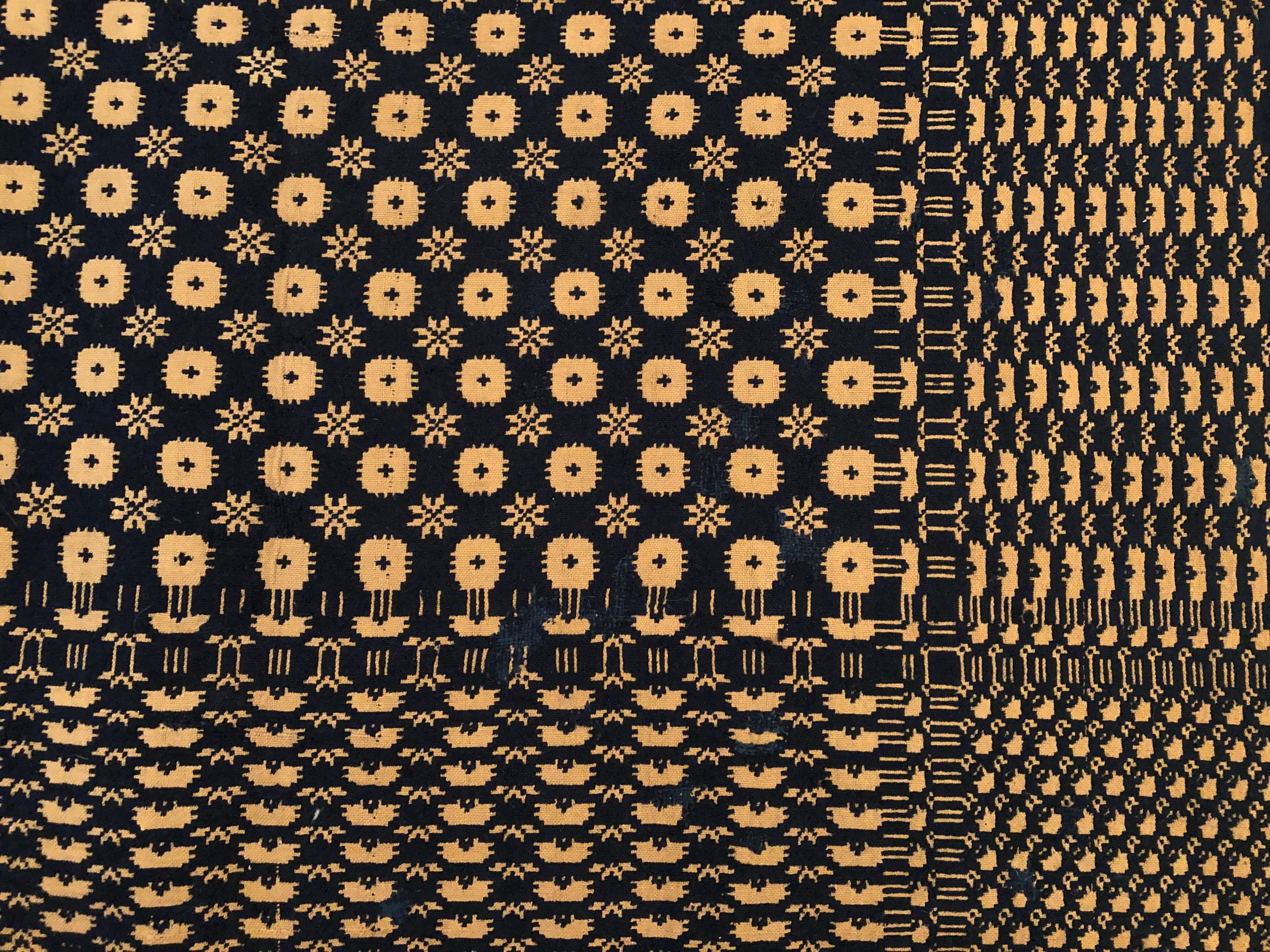

Most coverlets were woven in a weave structure called double-cloth, using undyed cotton or linen and indigo-dyed wool. Double-cloth coverlets are created by weaving two layers of fabric simultaneously, each layer intersecting at specific points to produce the pattern. The resulting fabric is reversible, with one side predominantly dark and the other side predominantly light. Weavers often wove coverlets in two or three narrow panels to accommodate the width of the loom. They would then seam the panels together to create a larger coverlet.

There are distinct stylistic and structural differences between coverlets made in different areas of the country, even between central New York and Long Island! Preservation Long Island has a total of 24 coverlets in the collection, most of which can definitively be traced to Long Island weavers. The jumping off point for my research was Woven History: The Technology and Innovation of Long Island Coverlets, 1800-1860, a catalog written by Susan Rabbit Goody for an exhibition by Preservation Long Island in the early 1990s. In the years leading up to the exhibition, Susan and the team compiled an inventory of extant Long Island coverlets in the collections of museums and historical societies across Long Island. They sorted the coverlets into two main styles, “geometric” and “figured and fancy,” and identified common variations within those styles seen on Long Island. I’d like to share an example of each style from the collection of Preservation Long Island and identify some trademarks of Long Island coverlets.

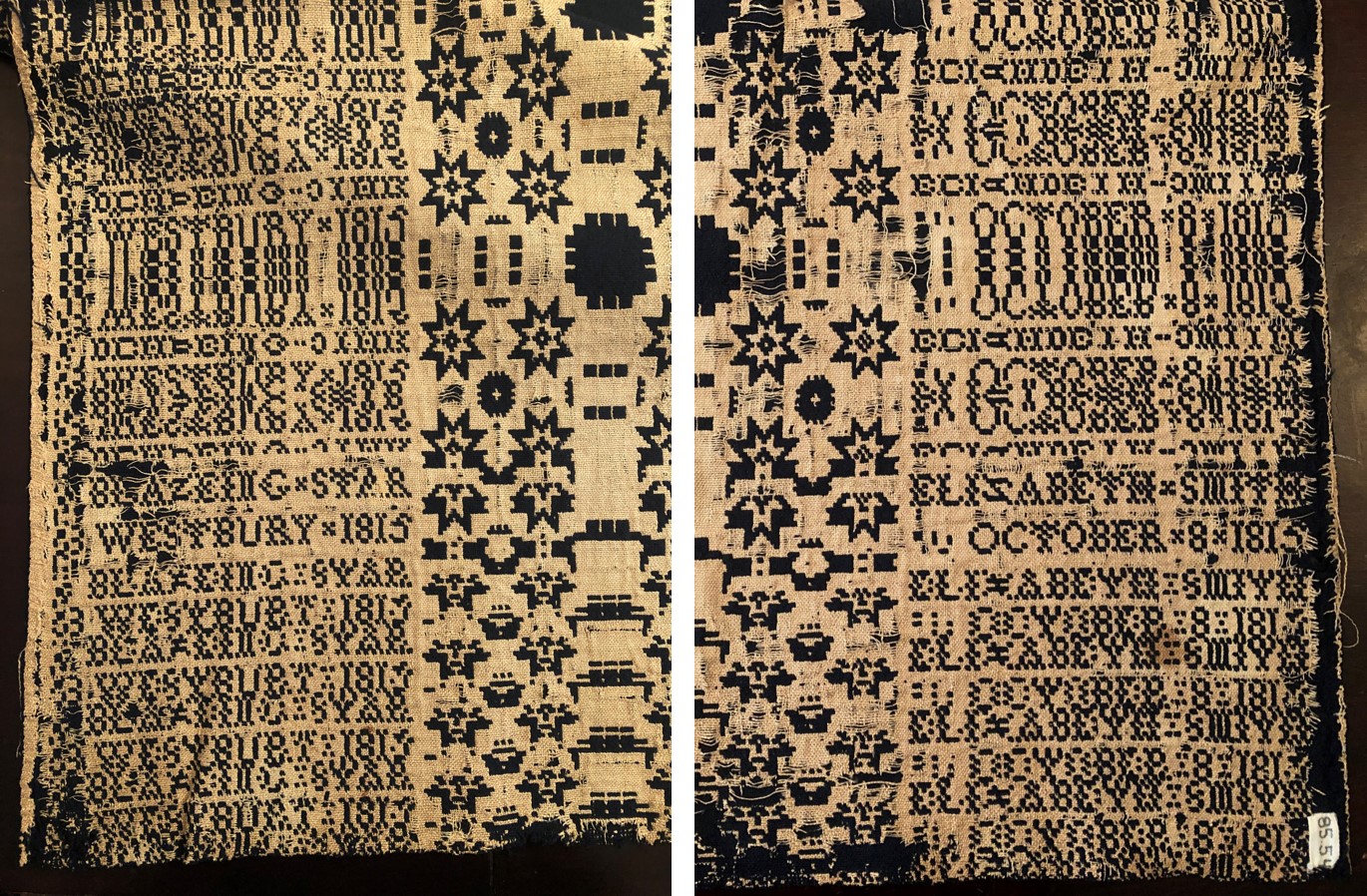

One of my favorite geometric coverlets in the collection is one woven for Elizabeth Smith in Westbury in 1816. The weaver used bleached linen and indigo-dyed wool to weave two panels (each 41” wide) that were seamed down the middle with a whip stitch. The finished coverlet is 97” long and 82” wide. The top corners have “Blazeing Star / Westbury 1816” and “Elizabeth Smith / October 8 1816” woven lengthwise in the warp direction. The names and dates are legible once from the predominantly light side of the coverlet, and appear multiple times in a distorted style along the top border. Early looms were not equipped to weave individual letters and numbers, resulting in distorted patterns in the border due to the way the threads had to be grouped to make the pattern blocks for the names and dates in the corners. The other three borders, down either side and across the bottom edge, contain a repeated portion of the pattern in the center field.

While many Long Island coverlets are named and dated, this one is unusual in that it also contains the location and name of the pattern! The earliest named and dated Long Island coverlets contain variations of this “Blazing Star” pattern, also known as “Blazing Star and Snowball.” Many coverlets in this pattern are believed to have come out of the Mott Mill in Westbury, though stylistic differences make it impossible to attribute them conclusively. However, the inclusion of “Blazeing Star” and “Westbury” on this example strongly suggest that it was indeed a product of the Mott Mill. The same star and snowball shapes are also present on the Catharine Onderdonk coverlet, woven just a year later in 1817.

As seen in the examples above, geometric coverlets have stepped patterns with small repeats, and borders that are partial repeats of the center field. As weaving technology evolved, it became possible to weave coverlets with more complex, curvilinear designs with distinct patterns in the center field, borders, and corner blocks. These “figured and fancy” coverlets gradually replaced the geometric coverlets, becoming the primary style by the 1830s and 1840s.

Most of the extant figured and fancy coverlets have an eight-pointed star, or starburst, in the corner blocks paired with one of three different border patterns: stylized tulips in circles, stylized double vines and buds, or a grapevine with leaves and grapes. The center fields typically contain stylized floral medallions of various sizes organized in a repeating grid. These similarities indicate that weavers were not working in isolation, but rather shared and copied designs freely. It is possible that weavers became familiar with certain designs while training under another weaver and later continued creating similar motifs in their own shops.

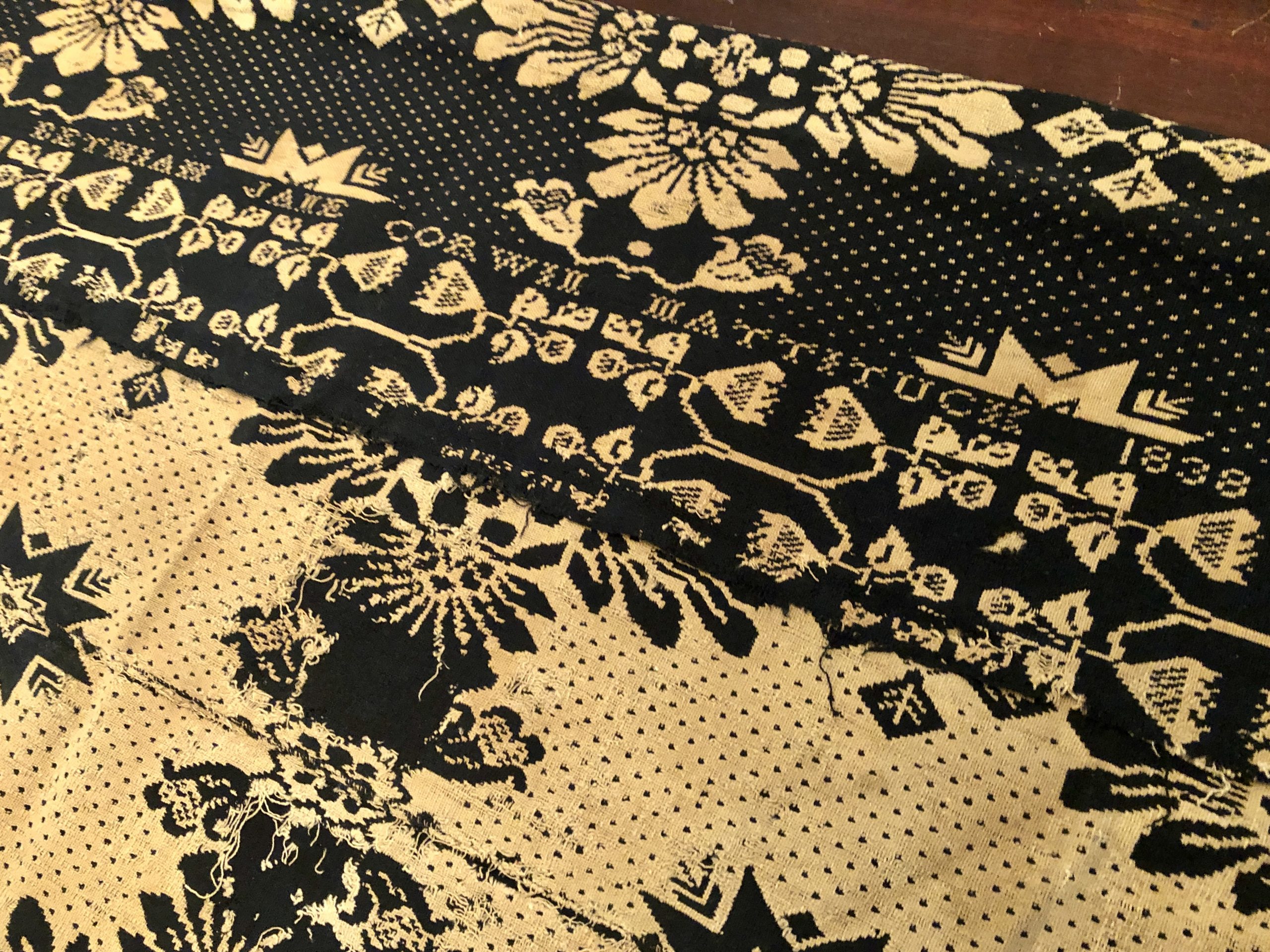

I really enjoyed studying a coverlet woven for Bethiah Jane Corwin in Mattituck in 1838 because of the family history I was able to uncover. The weaver used undyed cotton and indigo-dyed wool to weave two panels (each 37” wide) that were seamed down the middle. The finished coverlet is 86” long and 74” wide. The coverlet has the typical starburst corner block with the stylized double vines and buds border. Interestingly, the center field contains the same starburst from the corner blocks, which alternate with large and small floral medallions and a four-pointed diamond motif on a dotted background. “Bethiah Jane Corwin Mattituck 1838” is woven lengthwise in the warp direction in the space between the border and center field. It appears on one panel only and is legible from the predominantly blue side.

Bethiah was born on August 12, 1833 near Aquebogue to John Corwin and Bethiah (Griffin) Corwin. She was the youngest of ten children and was baptized at the Mattituck Presbyterian Church on June 15, 1834. There are several nearly identical coverlets included in the inventory in Woven History; all were woven between 1838 and 1840, including one woven for Fanny Corwin of Mattituck in 1838 (now in a private collection). As I continued searching census records I discovered that Fanny was Bethiah’s older sister! It was fun to imagine the family visiting their local weaver to order matching coverlets for their daughters. Further research revealed that the Corwin’s had a third daughter, Ann, leaving me to wonder whether a third matching coverlet ever existed and will one day turn up.

While it is fascinating that we can pinpoint these coverlets to a certain date and place, and sometimes even to a specific maker, it is equally fascinating to think about the larger context in which they were produced. They were not simply products of individual weavers working on Long Island, but rather the result of a vast national and international textile industry. These coverlets would not exist without the weaving knowledge and technology brought over by European immigrants, an international indigo market that continued the centuries-old practice of dyeing textiles blue, and a seemingly unlimited supply of cotton produced by networks of enslaved labor and factory systems.

There is so much more to investigate when it comes to uncovering the history of coverlet weaving on Long Island. What we know has been pieced together from varied sources such as account books, diaries, census records, advertisements, and the actual coverlets themselves. It is an ever-evolving field, open to new interpretation as previously unknown sources and coverlets continue to be discovered.

Just this year, a previously unknown Long Island coverlet was donated to Preservation Long Island! Part of my internship involved studying the coverlet and writing a proposal for accession. It was woven in the “Blazing Star and Snowballs” pattern in 1812 for Catharine Cock, who lived in Matinecock between 1792 and 1875. The top corners have “Catharine Cock” and “2 Month 28 1812” woven lengthwise in the warp direction. It is now the oldest named and dated coverlet in Preservation Long Island’s collection. It was exciting to fit this new coverlet into what we know about Long Island coverlets and weavers!

Because the majority of my graduate school experience was shifted to online learning due to the pandemic, it has been rewarding to be able to spend this time examining and caring for these objects in person. I enjoy photographing different coverlets each week and taking notes on things like the dimensions, fiber type, weave structure, design elements, and woven inscriptions. This internship has not only helped me to expand my knowledge of coverlets, but also my knowledge of Long Island history and genealogy. It’s been so interesting to study local history through textiles and I can’t wait to continue piecing together a more complete history of Long Island weavers.

By Emily Werner, Collections & Curatorial Intern

Published October 18, 2021