This post is part of a blog series connected to Preservation Long Island’s Jupiter Hammon Project, a multi-year initiative launched in 2020 to reevaluate how Preservation Long Island engages visitors at Joseph Lloyd Manor (completed 1767) with the site’s history of enslavement and the story of Jupiter Hammon, one of the earliest published African American writers.

Jupiter Hammon (1711–ca. 1806) was one of two enslaved writers in North America to publish works during the eighteenth century. The other was Phillis Wheatley Peters (ca.1753–1784). During her short life, Wheatley Peters gained international renown for her intelligence and skill with a quill pen. At just twelve or thirteen, she published her first poem. It appeared in the Newport Mercury in December of 1767, seven years after the publication of Hammon’s earliest known piece, An Evening Thought. Hammon’s and Wheatley’s extraordinary literary achievements offer exceptionally rare perspectives on the spiritual, social, and political worlds of Revolutionary America and the complexities of race and enslavement in the young United States. Both were evangelical writers whose poetry and prose reflected their deep Christian faiths and contributed to larger discussions about liberty and slavery on both sides of the Atlantic.

While Hammon was born into slavery on Long Island, Wheatley was born in the Senegambia region of West Africa, kidnapped into slavery, and forced to endure the Middle Passage. She arrived in Boston on July 11, 1761 and was one of the 75 out of 96 captive Africans that survived the treacherous journey. John Wheatley (1703–1778), a Boston merchant and tailor, purchased the seven- or eight-year-old child to serve as an enslaved domestic laborer for his wife, Susanna. They named her “Phillis” after the slave ship that forcibly removed her from her homeland. Although Phillis initially spoke no English, she mastered the language and quickly learned to read and write.

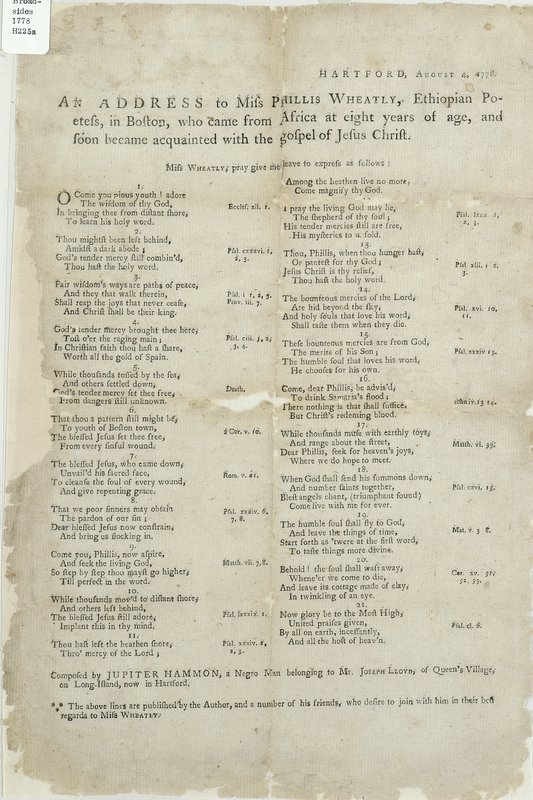

At nineteen or twenty, Phillis Wheatley released a collected volume of poetry, the first book by a Black American poet. Published in London in 1773, Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral demonstrated her devout Christian beliefs and philosophical interests while addressing political issues of the day from the repeal of the Stamp Act to slavery. Shortly after its publication, Phillis gained her freedom, and five years later, Jupiter Hammon sat down to compose a friendly response to Wheatley’s work. He was nearly 67 years old and writing from exile in Hartford, Connecticut. Two years had passed since he and Joseph Lloyd (1716–1780) had fled the Manor of Queens Village as the British marched into town following American defeat at the Battle of Long Island.

In his “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley,” Hammon writes to the famous young poet in verse, celebrating their shared African heritage and instruction in Christianity. His words echo Wheatley’s own poem, “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” Hammon writes: “God’s tender mercy brought thee here;/ Tost o’er the raging main;/ In Christian faith thou hast a share,/ Worth all the gold of Spain.” More than four decades Wheatley’s senior, Hammon acts as a mentor and gently argues against her preoccupation with worldly matters over spiritual salvation. It is unknown if Wheatley ever responded to the elder poet.

Despite the religious overtones of Jupiter Hammon’s works, he also addressed the historic events that unfolded around him. Hammon was critical of chattel slavery and the American Revolution. Twice he would have to flee invading British forces, first on Long Island in 1776, and then again in 1779 as English troops brought death and destruction to the city of New Haven, Connecticut. The following year, Joseph Lloyd, Hammon’s enslaver and a supporter of American independence, tragically died by suicide. Hammon’s 1778 poem, “A Dialogue, Entitled, The Kind Master and the Dutiful Servant,” directly references the ongoing war, expressing a desire to see its end, and through imagined dialogue between a “master” and a “servant,” reveals Hammon’s complex feelings about the relationship between God, humanity, and slavery.

Phillis Wheatley did not fully share Hammon’s views. Despite the Loyalist leanings of her former enslavers, she supported independence and hoped that the rhetoric of freedom espoused by the Patriotic cause would lead to demise of slavery in America. In 1775, she pledged her allegiance to the war effort in a letter and poem to George Washington. The general was so moved by Wheatley’s “poetical talents,” that he published the poem on her behalf and invited her to visit him in Cambridge.

Over the course of her life, Phillis Wheatley Peters authored at least 57 pieces of poetry, 46 of which she lived to see published. Her works collected praise from the likes of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Voltaire, and even King George III. Wheatley Peters died a free woman in 1784 at just 31 years old, likely due to complications from childbirth. She had been married to a free man named John Peters, but the couple struggled to make ends meet. For free Blacks in early America, jobs were hard to come by and the pay was often not enough to live on. Before Wheatley Peters passed away, she attempted to publish a second book, but was never able to secure the financial support. John Peters was probably the last person to see the manuscript.

Pioneers in American literature, Jupiter Hammon and Phillis Wheatley Peters laid the foundations for Black intellectualism in America. Their literary accomplishments were extraordinary in a society that would come to embrace white-supremacist views about the intellectual inferiority of Africans. With his address to the “Ethiopian Poetess,” Hammon engaged a fellow “genius in bondage” in a philosophical exchange of ideas that was unprecedented in eighteenth-century America. As war broke out in the colonies and debates about freedom reverberated across the Atlantic, Hammon’s and Wheatley’s insightful words critically deepen our understanding of American freedom and the turbulent historical moment in which they both lived and survived.