By Sarah Kautz, Preservation Director, Preservation Long Island. Originally published February 2019.

Update Spring 2020: Preservation Long Island is excited to share some great news from the community of Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah subdivisions (SANS): SANS is now listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places! This community-driven effort received a 2019 New York State Historic Preservation Award and a 2020 Project Excellence Award from Preservation Long Island.

The SANS cultural resources survey and National Register nomination was self-funded by SANS residents, with financial assistance and grant submissions provided by the Sag Harbor Partnership, a local not-for-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and enhancement of the quality of life in the village. The SANS survey project was awarded a $6,400 Preserve NY grant and an additional $4,600 grant from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation.

After the Village of Sag Harbor declined the community’s requests to officially sponsor the survey project in 2017, the Sag Harbor Partnership agreed to serve as the fiscal sponsor for grant applications. More recently, however, Sag Harbor’s Village Board decided to sponsor a 2018 state grant in support of a $16,000 municipal survey to update the existing Sag Harbor Village Historic District, which borders the western portion of SANS. It is not yet known if village officials will incorporate SANS into their forthcoming reassessment of locally designated historic resources.

As the steward of Sag Harbor’s Custom House and the regional advocate for preservation on Long Island, Preservation Long Island has supported the self-funded efforts led by Renee Simons and her fellow SANS residents since 2016. Unfortunately, fast-paced redevelopment pressure coupled with real estate speculation continue to erode the historic landscape of SANS. This blog post shares some of the fascinating stories behind the creation of Azurest, the earliest of the three subdivisions, and highlights some of the urgent preservation needs now facing this remarkable community.

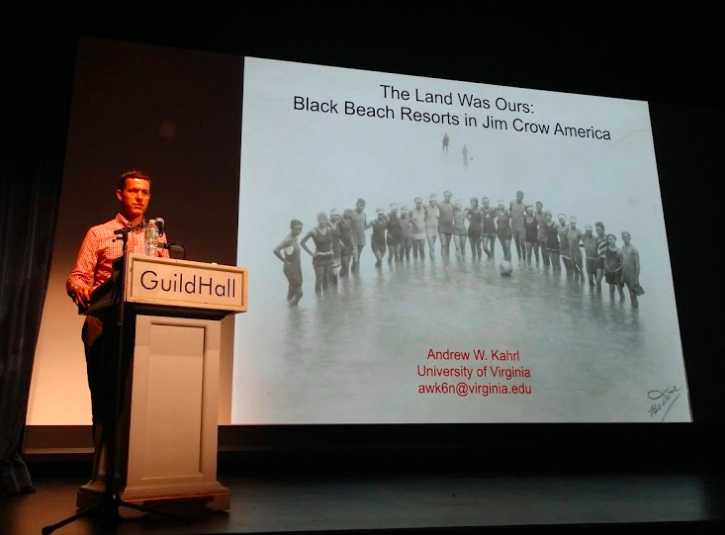

Located just east of the old Sag Harbor Village Historic District, African American families began purchasing property in SANS for summer retreats during the late 1940s when people of color faced widespread racial segregation, violence, and discrimination that prevented them from accessing beaches and resorts across the country.

SANS quickly emerged as a refuge during the late Jim Crow era, becoming a popular African American leisure destination and a bastion of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. Many prominent black leaders and professionals became SANS homeowners, such as Roscoe C. Brown Jr. (1922–2016), who was a decorated Tuskegee Airmen pilot, and Edward R. Dudley (1911–2005), a New York State Supreme Court Justice and the first African American appointed to serve as a U.S. Ambassador. Well-known celebrities like Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, and Harry Belafonte were also frequent visitors.

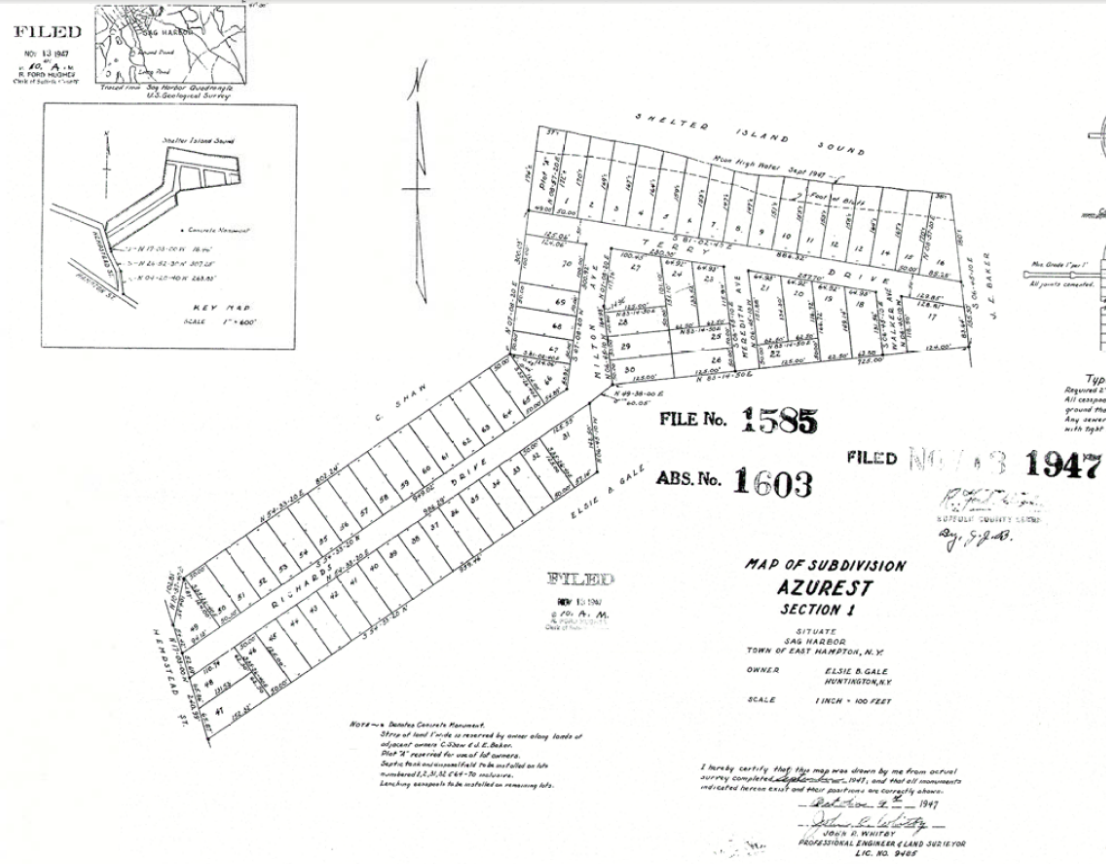

To mark Azurest’s 50th anniversary in 1997, the Sag Harbor Express featured a piece commemorating the subdivision’s founding in the 1940s, when Maude Terry (1887–1968), a Brooklyn schoolteacher vacationing at a rented cottage in Sag Harbor’s Eastville neighborhood, envisioned a new private summer community designed for black families on what was then an undeveloped 20-acre parcel between Hampton Street and Gardiner’s Bay. Mrs. Terry reached out to the property’s owner, Elsie B. Gale, whose husband, Daniel Gale, was struggling to sell the undesirable marshy wooded land, and they agreed on a plan to subdivide the parcel in partnership.

Maude Terry played a key role by finding prospective buyers for the newly created Azurest lots and went on to co-manage the Azurest Syndicate Inc., which brokered sales and financed mortgages for the subdivision. At a time when discriminatory practices like redlining otherwise prevented people of color from financing property, the Azurest Syndicate made it possible for African Americans to obtain mortgages and fund construction. Mrs. Terry managed the Syndicate with her sister, Amaza Lee Meredith, civil engineer James P. Smith, as well as attorney Dorothy C. “Dot” Spaulding and her husband James Edwin Spaulding.

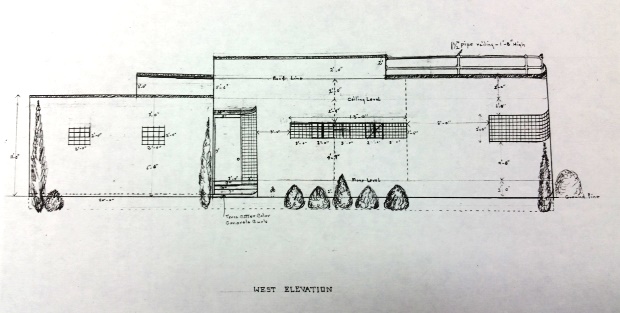

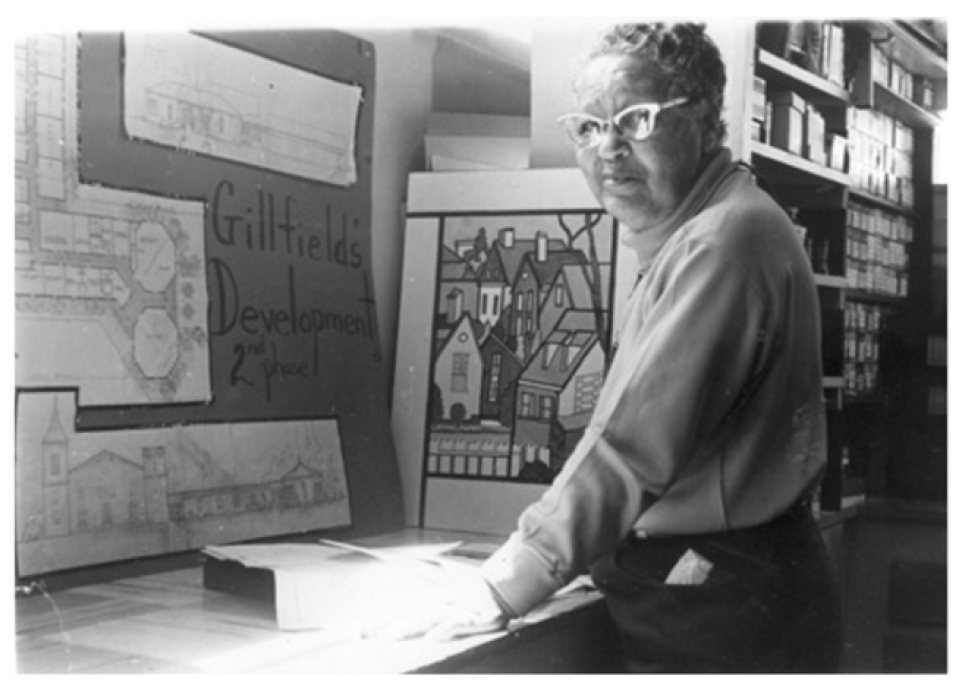

Better known for her work in Virginia, Amaza Lee Meredith (1895–1984) was an educator and artist, and one of the very first African American female architects. After earning B.A. and M.S. degrees at Columbia University between 1928 and 1934 (Maude Terry also attended Columbia University), Miss Meredith served as faculty at Virginia State University (VSU) from 1930 to 1958. She founded VSU’s Fine Arts Department and was appointed department chair in 1935. One of her most extraordinary designs is Azurest South, a modernist style-house built in 1939 on the VSU campus in Petersburg, where she lived with her partner, Edna Meade Colson.

Amaza Lee Meredith designed at least two residences in Sag Harbor’s Azurest neighborhood, including a house where she summered with her sister’s family, as well as Edendot, a house designed for the Spauldings, her friends and business partners. Documents from a substantial collection of drawings and blueprints found in the Amaza Lee Meredith Papers at VSU’s Johnston Memorial Library suggest she may have designed plans for a number of other houses in Sag Harbor.

Miss Meredith additionally served as secretary and archivist for the Azurest Syndicate. Just ten years after the founding of Azurest, she suspected the subdivision’s legacy would be significant: “Do you think that minutes should be kept of each meeting?”, Amaza asked in a 1958 letter, “In this way a complete history of the Syndicate will be recorded. I have the feeling that the organization is making history and none of it should be lost. (I fear some already is lost)”. Letter by Meredith as quoted by Grace Lynis Dubinson, “Slowly, Surely, One Plat, One Binder at a Time: Choking Out Jim Crow and the Development of the Azurest Syndicate Incorporated,” (M.A. Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012), 7-8.

Today, the rolling wooded hills of SANS still feature low-profile, mid-century ranches and bungalows built by early residents in the late 1940s and 1950s. However, as property values boom in Sag Harbor and elsewhere, driven largely by private equity firms and real estate speculation, the distinctive setting of historical communities are rapidly changing as existing properties are demolished, clear-cut, and consolidated to make way for substantially larger houses.

There is still much more to learn about the development of Azurest, a community founded by two remarkable black women entrepreneurs who, like many early SANS residents, came of age during the height of the Harlem Renaissance and helped launch the Civil Rights Movement. Other than Edendot and her summer house, we do not yet know how many houses Amaza Lee Meredith designed in SANS, or how many remain standing, but as one of the first black women to practice architecture professionally in America, her designs are incredibly significant. Any surviving examples would be worthy candidates for preservation.

From the platting of lots to the construction of houses, Azurest was thoughtfully planned and developed between the 1940s and 1960s, a period that coincided with the growth of the American Civil Rights Movement during the final decades of the Jim Crow era. However, since our 2016 Preservation Notes article on SANS was published, several houses dating to this important early period are already gone or slated for demolition.

Before the landscape of this historical community is irreversibly lost to demolition and redevelopment, Preservation Long Island encourages our friends and colleagues in the Sag Harbor community to support the ongoing campaign to recognize, celebrate, and protect the important legacy of SANS.