By Sarah Kautz, Preservation Director, Preservation Long Island

Originally published October 2018. Updated February 2022.

Preservation Long Island has been introducing visitors to Jupiter Hammon, one of America’s earliest published Black authors, at Joseph Lloyd Manor House since the house opened to the public in the 1980s. Hammon’s life and writings offer an exceptionally nuanced view of slavery and freedom on Long Island before and after the American Revolution. His works are especially significant because most literature and historical documents from the 18th century were not written from an enslaved person’s point of view. Consequently, Hammon’s writing provides powerful insight into the surprising contradictions of emancipation and the complexities of race in the newly formed United States.

Jupiter Hammon was born on October 17, 1711, at Henry Lloyd Manor House (built ca. 1711), the first

seat of the Manor of Queens Village (also known as Lloyd Manor or Lloyd Neck). Henry Lloyd (1685–1763) recorded Hammon’s birthday in a ledger book along with births, and some deaths, of other children born to enslaved parents at the Manor.

How and when did Jupiter Hammon learn to read and write? Did he learn as a child or later in life? Were the Lloyds supportive of his learning? The exact circumstances of Hammon’s education remains uncertain. He may have attended lessons at a small schoolhouse Henry Lloyd built for his children at the Manor in 1722. Unfortunately, there are no records to confirm that Hammon or any other enslaved children were educated at the schoolhouse. Enslaved children were expected to work in 18th-century America, so any education young Hammon received likely took place separately from the Lloyd children after his daily tasks were completed. Labor demands probably made it difficult for enslaved children and adults at the Manor to find time for educational activities.

By the mid-18th century, anti-literacy laws were enacted in places like South Carolina to prevent enslaved and freed people of color from learning to read and write. However, anti-literacy laws were uncommon in New York and New England, where influential Anglican and Congregational churches encouraged teaching enslaved and freed people to read the Bible. In light of the Lloyd family’s strong ties to Anglican and Congregational churches, they may have supported Hammon’s literacy for religious purposes. The Bible certainly figures prominently in Hammon’s writing and he recommended a pious approach to literacy for both free and enslaved African Americans. For example, in his 1786 essay, An Address to the Negroes in the State of New York, Hammon advises his audience to “Let all the time you can get be spent in trying to learn to read. Get those who can read to learn you, but remember, that what you learn for, is to read the Bible. If there was no Bible, it would be no matter whether you could read or not. Reading other books would do you no good.”

Hammon’s writing skills are especially noteworthy since learning to read was much different than learning to write during the 18th century. Writing required special supplies like parchment and ink, which were costly and difficult to acquire. For these reasons, writing was often limited to the wealthy elite, like the Lloyds. Nevertheless, Hammon learned to write and became an accomplished author. For this remarkable achievement, we celebrate him today as one of only two enslaved African American writers published in North America during the 18th century, the other is Phillis Wheatley (ca.1753–1784). Together with Wheatley, Hammon pioneered Black intellectualism in America, adding their voices to revolutionary discussions about liberty and slavery on both sides of the Atlantic.

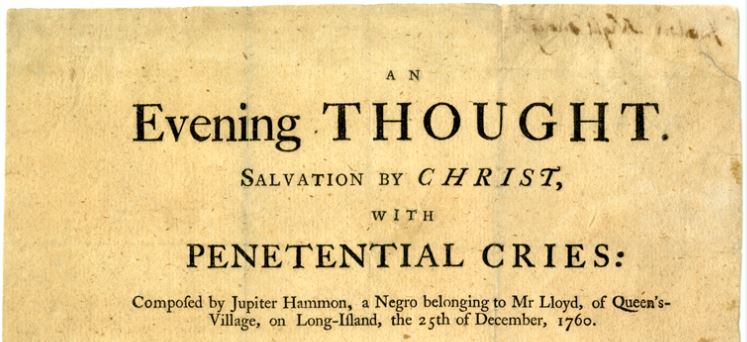

In addition to his literary talents, Hammon’s longevity is extremely noteworthy. Living into his 90s, he was enslaved by four generations of the Lloyd family and witnessed the American Revolution along with other pivotal events in our nation’s founding. Even among the wealthy privileged classes, such longevity was rare in 18th-century New York, but compared to other enslaved people at the time, Hammon’s long life is truly exceptional. The average life expectancy of enslaved people in New York was dismally short, as revealed by the skeletal remains of 301 individuals interred at the New York African Burial Ground during Hammon’s lifetime (see The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground). Evidence shows the average life expectancy for captured Africans and their descendants in New York was between 24 and 30 years of age. Just 14 individuals were 55 or older when they died, and more than half of those interred were young children. By contrast, when Jupiter Hammon published his first poem, An Evening Thought, in 1761, he was nearly 50 years old and had already outlived most of his peers. Hammon spent another 30 years in bondage, apparently working as a servant, clerk, and courier for the Lloyds while composing revolutionary poetry and essays.

Long before the end of slavery in the United States, literacy gave Hammon the freedom to explore ideas and express himself intellectually despite his enslavement. In addition to authoring two unpublished poems found at Yale University in 2011 and the New-York Historical Society in 2015, he published at least six poems and three essays. Of course, more of his poems and essays could still be found! Until then, Jupiter Hammon’s relatively modest but profound oeuvre speaks to us today, conveying his distinctive voice, sharing his pain and hope for freedom in the United States of America.

Tours of Joseph Lloyd Manor House are available by appointment only. Please call 631-692-4664 or email [email protected] for more information.

Tours of Henry Lloyd Manor House are available by appointment only. Please contact the Lloyd Harbor Historical Society at (631) 424-6110 or email [email protected].

Explore some of the fascinating people and places in Jupiter Hammon’s world with our interactive story map (click on the image below):

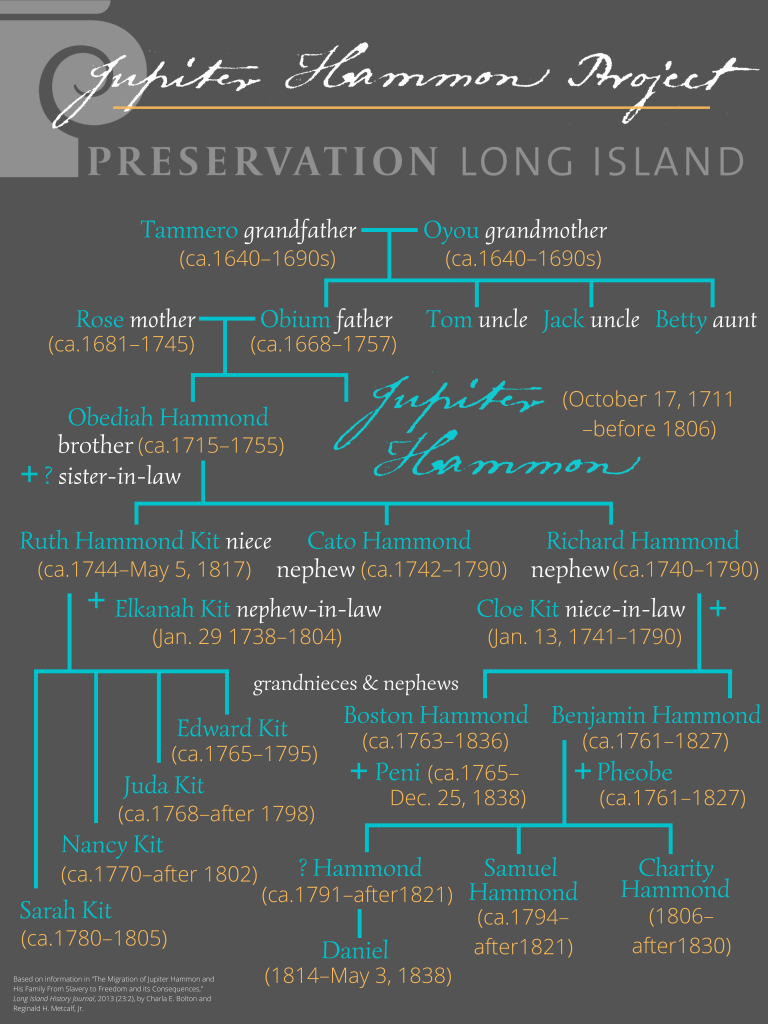

In addition to Jupiter Hammon’s writings, members of his extended family are remarkably well-documented in the records of the Lloyd family and other archival sources.