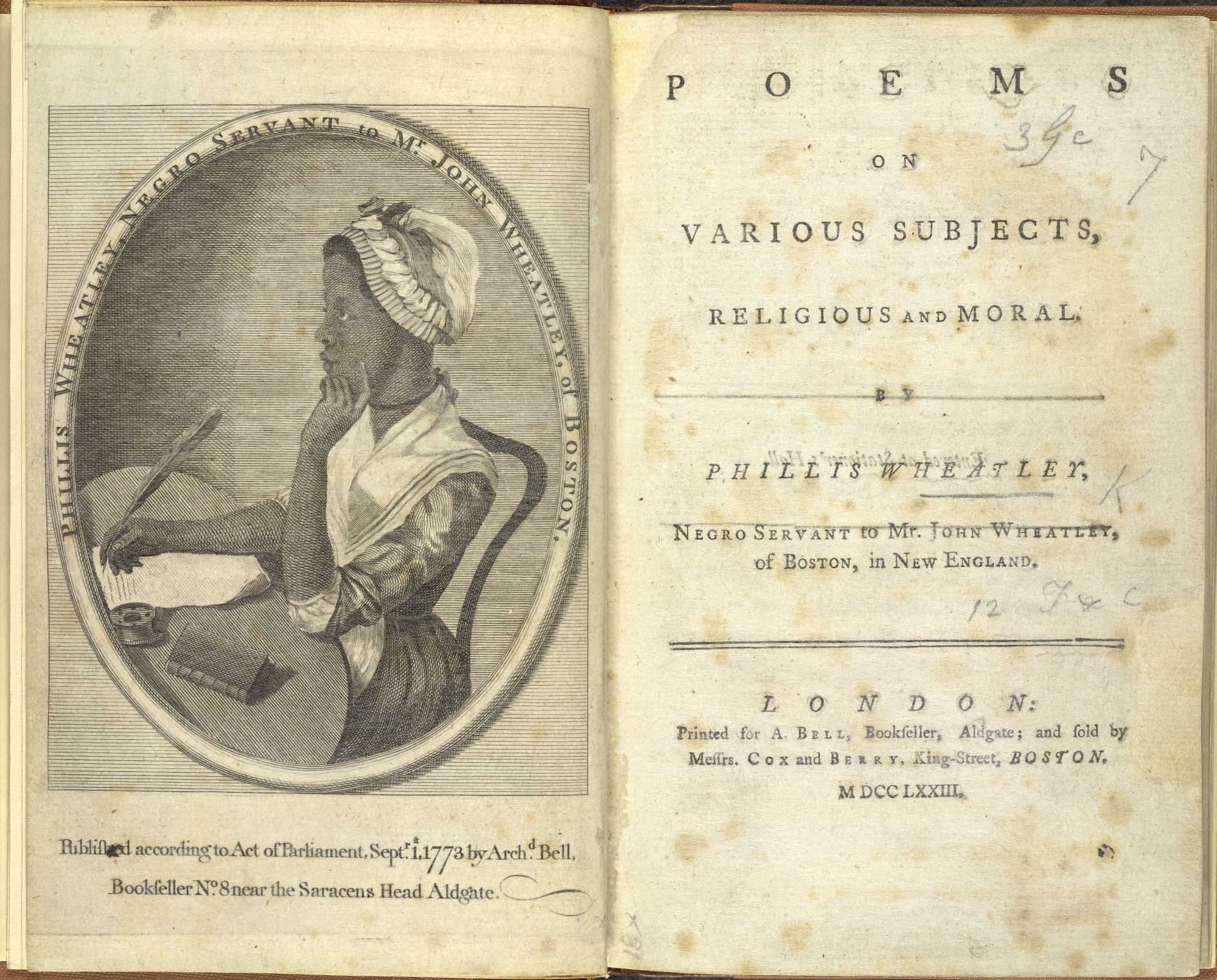

Preservation Long Island’s ongoing Jupiter Hammon Project has encouraged us to reread and rethink documentary evidence about Jupiter Hammon (1711–before 1806) and the influence of contemporary women writers such as Phillis Wheatley Peters (ca.1753–1784), the first African American to publish a volume of poetry, and Mary Clark Lloyd (1681–1749), the second wife of Henry Lloyd (1685–1763).

Known for being a devout and contemplative Christian, Mary Clark was widowed twice before she married Henry Lloyd in 1729. Notably, her first husband was Reverend Ebenezer Pemberton Sr. (1672–1717), a bibliophile and the third pastor of Boston’s Old South Church, the same congregation Phillis Wheatley joined decades later. Through Mary Clark Lloyd, Hammon and his family were likely exposed to Boston Congregationalist teachings, a departure from Henry Lloyd’s Anglicanism. It was only after his marriage to Mary Clark that several of the people the Lloyds enslaved were baptized by Reverend Ebenezer Prime at the First Church of Huntington, including Jupiter Hammon’s father, Obium. From his father, Hammon inherited a Book of Psalms and a dedication to reading and religious verse that was further encouraged by his enslavers.

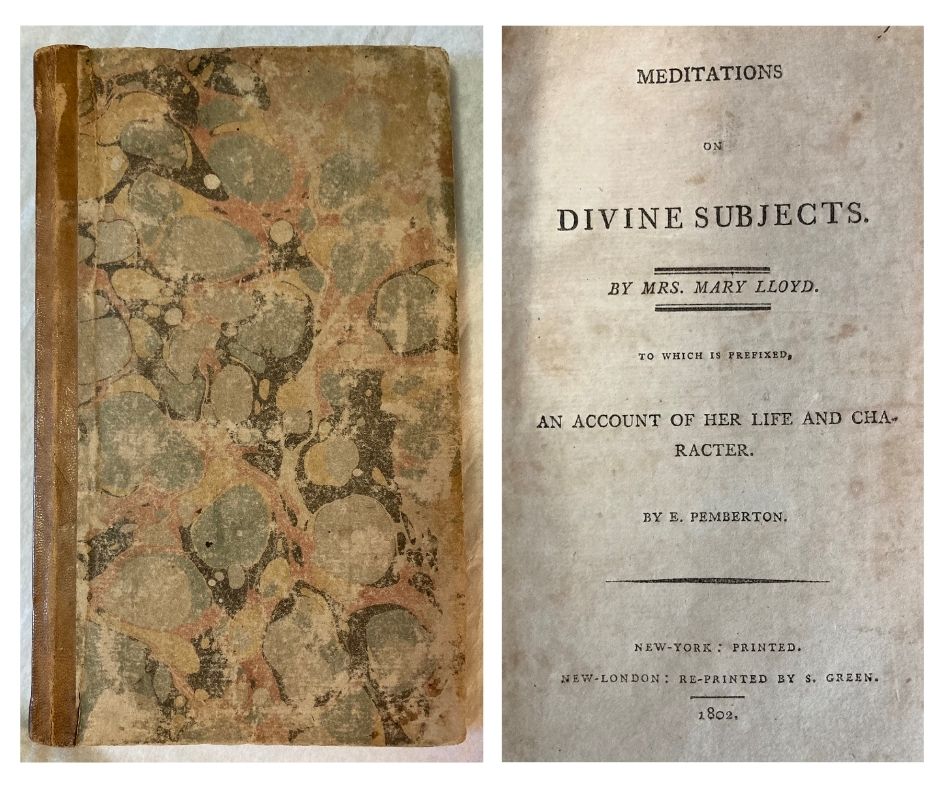

Preservation Long Island recently acquired a book of religious writings by Mary Lloyd entitled Meditations on Divine Subjects. It was posthumously published in New York in 1750 by Mary’s son, Ebenezer Pemberton, Jr. (1705–1777). The volume was a tribute to his late mother and a dedication to his stepfather, Henry Lloyd. Preservation Long Island’s volume is an 1802 edition consisting of 88 pages printed in octavo and bound between two marbled paper boards with a leather spine.

Prefixed to Mary Lloyd’s writings is an account of her life and character by Ebenezer Pemberton, Jr. In it, he describes his mother’s life-long devotion to scripture, her experience moving from populous Boston to remote Long Island, and her insistence that domestic servants (who were enslaved) observed the Sabbath—a time she used to instruct and educate those around her on religious subjects. Mary Lloyd was present in Jupiter Hammon’s life throughout his young adulthood and likely played an instrumental role in his education and religious upbringing.

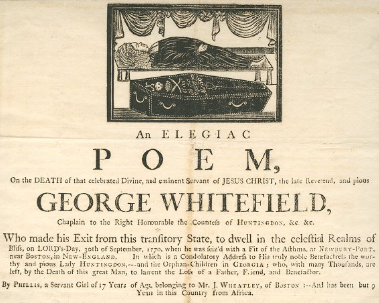

Through Mary’s son Ebenezer, Hammon was also connected to another prominent eighteenth-century literary woman: Phillis Wheatley Peters, the only other person to publish in North America while enslaved during the eighteenth century. Ebenezer Pemberton, Jr. was a Congregationalist minister who supported famed evangelist George Whitefield (1714–1770). Pemberton delivered a sermon upon Whitefield’s death in 1770; appended to a printed version of the eulogy was Phillis Wheatley’s own poetic tribute to the evangelical preacher.

Pemberton personally knew Wheatley. He was one of the eighteen influential Bostonians who verified the authorship of her poetry and whose attestation is included in the preface to Wheatley’s publication, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). The following year, Pemberton delivered a letter and a copy of the book to Obour Tanner, an enslaved woman and friend in Rhode Island, on Wheatley’s behalf.

Phillis Wheatley achieved international fame with the publication of her volume of poetry. Jupiter Hammon was one of the many readers, on both sides of the Atlantic, inspired by her works. In 1778, while in exile in Connecticut during the Revolutionary War, Hammon addressed the famous poet in printed verse. Although there are no surviving records that point to a friendship between the two enslaved authors, they were personally connected through Ebenezer Pemberton, Jr., the stepbrother of Hammon’s enslaver, Joseph Lloyd (1716–1780). It is unclear if Hammon and Wheatley ever met, but Joseph spent the summer of 1770 in Boston with his brother, Dr. James Lloyd (1728–1810). In August of that same year, Hammon authored a poem addressed to the “youth of Boston town.” Hammon likely stayed with Joseph in the city and may have crossed paths with the much younger poet.

These exciting insights emerged from our efforts to revisit some familiar sources concerning Hammon and the Lloyd family. Overall, this evidence suggests Mary Lloyd and Phillis Wheatley each played a more significant role in the social and intellectual world of Jupiter Hammon than previously acknowledged. We look forward to sharing more fresh perspectives as the Jupiter Hammon Project continues!

By Lauren Brincat, Curator and Sarah Kautz, Preservation Director, Preservation Long Island

Published March 30, 2021