This month we will host the Huntington chapter of the League of Women Voters at the Voices and Votes exhibition. Women have only had the vote in the United States since 1920, but they have been at the center of Historic Preservation advocacy for much longer. Before they could cast a ballot, women were organizing and speaking up to save our historic heritage. They have continued to be at the center of the movement and were crucial to the founding and shaping of advocacy in our organization.

Women in the Early Historic Preservation Movement

The seeds of the historic preservation movement can be traced back to the early 19th century, amidst economic downturns and shifting social landscapes. In 1830, when progress on Boston’s Bunker Hill Memorial stalled due to an economic depression, Sarah Josepha Hale (1788–1879) led a women’s committee to complete the monument. The women, many of whom had experienced the sacrifices of war through their grandmothers, embraced the opportunity to honor the memory of the Bunker Hill martyrs. Due to the fundraising leadership by women, the monument was completed. Ultimately, as one observer noted, what was initiated by men was completed by women.

The rescue of George Washington’s Mount Vernon from neglect is recognized as one of the first acts of historic preservation advocacy in the United States. In 1853, Ann Pamela Cunningham (1816–1875) spearheaded the rescue of the estate, forming the Mt. Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA). Cunningham’s initiative led to a pioneering nationwide fundraising campaign that raised $200,000 to purchase and preserve Mount Vernon. In 1858, the MVLA successfully acquired the estate from the Washington family and took on the responsibility of its maintenance and restoration. This grassroots effort by the MVLA was one of the earliest and most successful examples of historic preservation by a private organization in the United States.

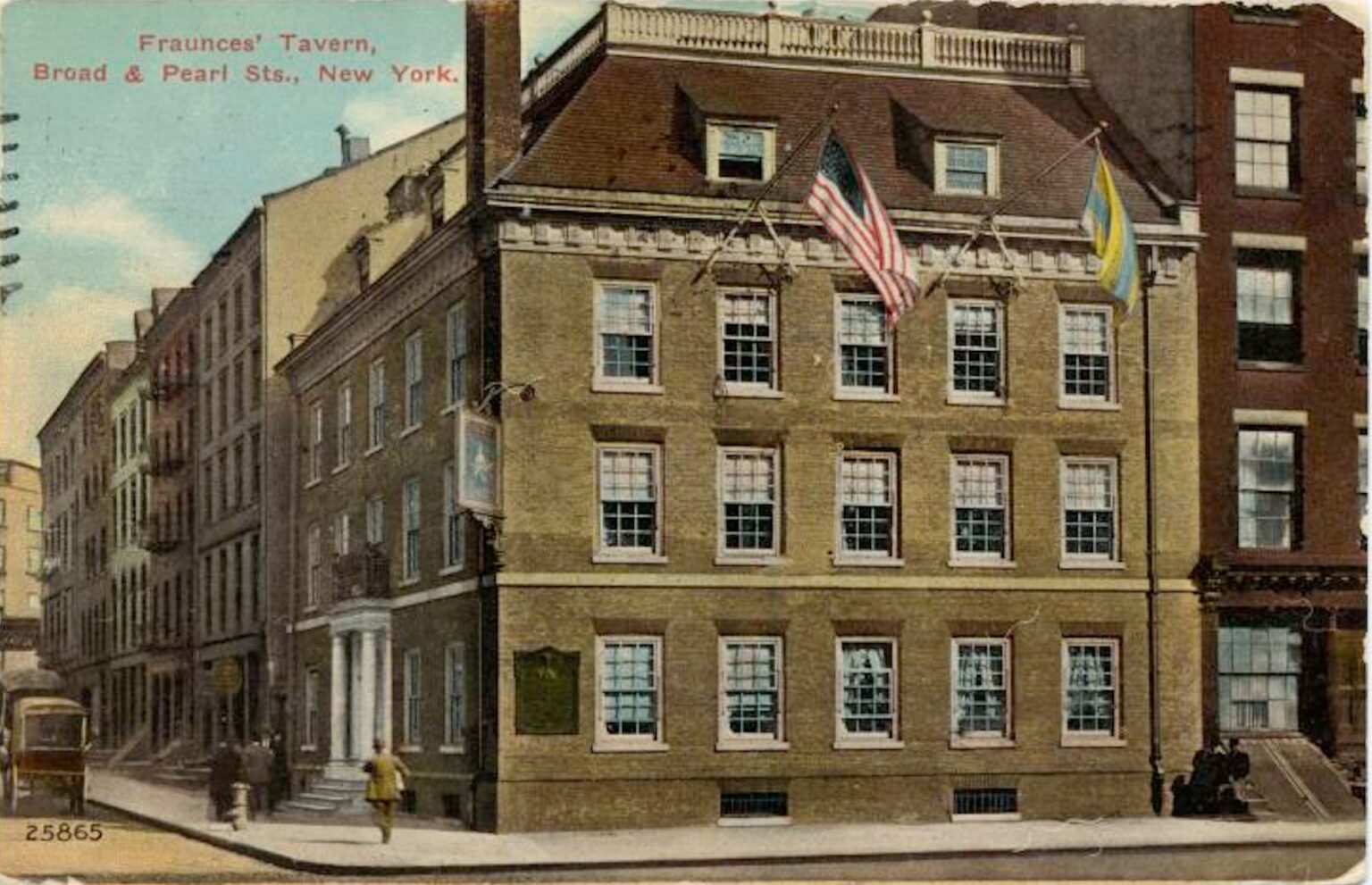

In New York City, Melusina Peirce (1836–1923) played a pivotal role in the preservation of Fraunces Tavern, a historic landmark associated with Revolutionary War history. Peirce became involved in efforts to save Fraunces Tavern from demolition in the early 20th century. The tavern, where George Washington famously bid farewell to his officers after the war, faced the threat of destruction due to urban development plans. Peirce, recognizing its historical significance, spearheaded a campaign to raise awareness and funds for its preservation. Her efforts ultimately led to the establishment of the Fraunces Tavern Museum, which opened to the public in 1907.

Early efforts continued to focus on the founding of the United States and commemorating the Revolution. Further north in Boston, Mary Hemenway (1820–1894) played a key role in the preservation of the Old South Meeting House in 1876. At that time, the historic building, known for its association with revolutionary events like the Boston Tea Party, was at risk of being demolished due to neglect. Hemenway organized a successful campaign to raise funds for the restoration of the Old South Meeting House, rallying support from influential figures and community members.

By the turn of the century, other stories were beginning to be told. Frederick Douglass purchased his home, Cedar Hill, in 1877 and lived there until his passing in 1895, leaving the property to his wife, Helen Pitts Douglass.

Recognizing its historical significance, Helen worked tirelessly to preserve the house for public visitation, envisioning it as a site for pilgrimage. Congress established the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association (FDMHA) in 1900 to maintain the house. After Helen’s death in 1903, the FDMHA collaborated with the National Association for Colored Women (NACW) to restore the property, led by civil rights advocate Mary B. Talbert. Talbert’s influential call to action in The Crisis magazine rallied support, resulting in the NACW paying off the house’s mortgage in 1918. She believed that achieving their goal required the united effort of every African American in the country, stressing the need to mobilize all resources to secure the home’s preservation and showcase their commitment and capability as a community. This influential campaign led by Talbert ultimately contributed to the successful restoration and ongoing legacy of Frederick Douglass’s historic home. This achievement marked the centennial of Douglass’s birth and initiated a successful fundraising campaign that raised $11,000 for restoration efforts over four years. In 1962, Cedar Hill became part of the National Park System.

Interest in the origins of the United States grew with the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, kindling a renewed passion for historical collections and sites. By the 1890s, before women secured the right to vote, they were already ardent preservationists—advocating for the history they believed was important to save.

Early Advocacy and Preservation on Long Island

Preservation Long Island recognizes two women, Constance Hare and Barbara Van Liew, as the pioneers and leaders who shaped early advocacy in our organization.

Constance Hare (1893–1982) galvanized a women’s committee to create lasting change on Long Island. The steering group also prepared a list of “key women in twenty-two sections of Long Island,” who would be asked to enlist other members. By June 1950, the Women’s Committee had thirty-one members from twenty-three areas— “women of prominence from various parts of Long Island,” who served as zone chairmen for each area. The committee engaged in public education, spreading awareness of Long Island’s rich heritage through newsletters and outreach at garden club meetings. They undertook meticulous surveys of historic houses, compiling data and photographs that would become invaluable resources for future preservation endeavors. Notably, they extended their reach beyond buildings, documenting paintings, decorative arts, and even early water-powered mills—an interdisciplinary approach ahead of its time.

Beginning in the early 1950s, Barbara Ferris Van Liew (1910–2005) played a pivotal role in advocating for legislative measures to protect old houses. At the request of Constance Hare, Barbara prepared a report titled “Possible Legislative Aid in Saving Old Houses,” which garnered national and local attention. Her contributions underscored the importance of legal frameworks in safeguarding historic properties and laid the groundwork for subsequent preservation efforts on Long Island.

The survey work completed during this period under the supervision of (and often by) these women created the foundations for many of the historic districts and the recognition of many of the historic landmarks in our region. This work shaped what we saved and recognized as historically significant on Long Island.

The impact of these pioneering women extended far beyond architectural conservation. They challenged conventional gender roles, asserting their rightful place as custodians of history and guardians of cultural continuity. Their endeavors not only saved physical structures but also redefined notions of heritage, emphasizing its intrinsic value to communities. Their collective efforts constituted a profound women’s movement—one characterized by resilience, resourcefulness, and a passion to preserve the past for future generations.

By Tara Cubie

Preservation Director

Published April 22, 2024

Further Reading

Bunker Hill Monument Association: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bhma.htm

Fraunces Tavern Museum: https://www.frauncestavernmuseum.org/wrw-preservation-movement

Mount Auburn Cemetery: Hemenway https://www.mountauburn.org/mary-porter-tileston-hemenway-1820-1894/

Frederick Douglass House: https://www.nps.gov/frdo/index.htm